Steve and David

Let’s try a simple experiment. Imagine that you’re an admissions officer at a competitive college, and you’re evaluating the following two applicants:

- David — He is captain of the track team and took Japanese calligraphy lessons throughout high school; he wrote his application essay on the challenge of leading the track team to the division championship meet.

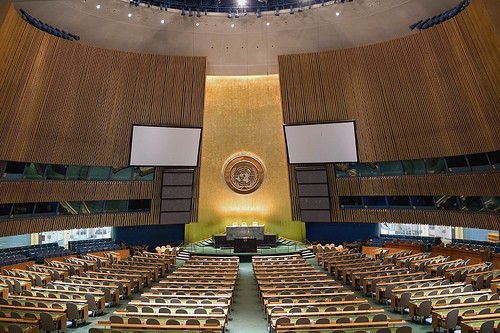

- Steve — He does marketing for a sustainability-focused NGO; he wrote his application essay about lobbying delegates at the UN climate change conference in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Who impresses you more?

For most people, there’s little debate: Steve is the star.

But here’s the crucial follow-up question: Why is Steve more impressive than David?

The answer seems obvious, but as you’ll soon discover, the closer you look, the more hazy it becomes. To really understand Steve’s appeal, we will delve into the recesses of human psychology and discover a subtle but devastatingly power effect that will change your understanding of what it takes to stand out.

Steve’s Story

Steve is a real student, one of the many I profile in my new book on students who get into good colleges while still enjoying their high school lives. He currently attends Columbia University, which he describes as: “a school I would have never gotten into without my UN work.”

Here’s how his story unfolded…

As a high school sophomore, Steve stumbled into an opportunity to attend a UN conference in New York City, near where he lived. A believer in underscheduling, he had been “e-mailing every non-profit under the soon, looking for an unpaid internship.” Most organizations ignored him. One wrote back, however, and said they didn’t have a job for Steve, but they did have a slot for a student to accompany their delegation to an upcoming UN conference on children’s rights.

Steve jumped at the opportunity. He met delegates and learned about related NGOs. He even spoke up in a sub-committee meeting. This led to an invitation to attend an upcoming conference. And then another. In a short span, Steve became a UN insider.

“I loved it,” he recalls.

It was with this experience under his belt that, one year leader, Steve found himself in a conversation with a college student at a model congress conference.

“What sorts of things are you working on?”, she asked.

Steve mentioned the UN.

“The UN?”, she replied, “I work with them.”

As they continued to talk, the young woman revealed that she was involved with a non-profit called SustainUS — a group dedicated to helping American youth advocate for climate issues. SustainUS, at the time, had little money and no office — the employees were volunteers who worked virtually, mainly from college dorm rooms, organizing with Yahoo Groups and free web-based conference calls.

Steve proposed that he help the non-profit gain press coverage for their activism. “I like speaking with people, and I like writing, so that was a natural thing for me to work on,” he recalls. The group agreed.

“At 16, I was younger than the other members,” Steve told me. “But technology masked that.”

Over the next year, Steve called and e-mailed reporters, eventually scoring a few big hits, including a mention in Time Magazine’s Green Issue and a write-up in the Associated Press. As a reward for these efforts, the organization told Steve he could join the team traveling to the UN climate conference in Johannesburg to present a petition signed by American youth.

This was the experience Steve emphasized in his head-turning application essay.

Decoding Steve’s Story

With these details established, let’s return to our motivating question: Why is Steve more impressive than David? The obvious answers now spawn troubling complications:

- Explanation: Steve worked hard.

Issue: Being a varsity athlete requires many more hours of hard work than Steve’s efforts. - Explanation: Steve revealed brilliance or natural talent.

Issue: It’s hard to identify any specific brilliance or talent in Steve’s story. His path required him to attend conferences and send pitches to reporters. Being captain of a varsity sports team, by contrast, requires great natural ability — both in terms of athleticism and leadership. - Explanation: Steve showed “passionate” commitment.

Issue: So did David. He stuck with track through four grueling years and kept up his calligraphy throughout this same period. - Explanation: Steve did something unusual, creative, and outside the structure of the school.

Issue: Japanese calligraphy is also unusual, creative, and outside the structure of the school.

Steve’s impressiveness is intuitive and inescapable, but as the above exercise reveals, rationalizing this reaction proves tricky. To sidestep this obstacle, we must appeal to the curious psychology of social comparison.

Lassiter’s Insight

What happened inside your brain when you read the descriptions of David and Steve? According to a clever series of experiments conducted by G. Daniel Lassiter, a psychology professor at the University of Ohio, your first response was to look into the proverbial mirror. Or, as Lassiter describes it, somewhat more formally, in his 2002 paper on the subject: we have a “pervasive tendency…to use the self as a standard of comparison in [our] dispassionate judgments of others.”

Put another way, to evaluate a person’s accomplishments, we imagine ourselves attempting the same feat, allowing your own capabilities to provide a convenient benchmark for assessing others’.

(In Lassiter’s experiments, students took tests made up of difficult mathematical puzzles. He showed that when a student was asked to rate the intelligence of another student, this judging student used a self-assessment of his own intelligence, combined with how well he did on the test, to construct the rating.)

Let’s walk through the logic here. When you first encountered David and Steve, your brain began to compare them to yourself. In essence, your brain asked: “Could I do that? And if so, what would it require?”

For David, this question was easy to answer. Assuming you had more or less the same athletic ability, you could imagine yourself becoming captain of the track team: show up on time to practice, work hard, respect the coaches, etc. The Japanese calligraphy is even easier to imagine yourself learning — it requires only that you sign up for lessons. You might conclude that David has more natural athletic ability and is a harder worker than yourself, but neither of these assessments leads you to think of him as a star.

(Admissions officers would agree. They’re not looking to build hardworking and diligent classes. Instead, they want to build classes that are interesting.)

Then there’s Steve. Your attempts to mentally simulate Steve’s path likely derailed. How the hell does a 16-year old end up lobbying delegates at an international UN conference? Your failed simulation then lead to a powerful conclusion: he must possess something special. This conclusion is soon followed by a feeling of profound impressiveness.

I call this outcome the failed simulation effect, which I formally define as follows:

The Failed Simulation Effect

Accomplishments that are hard to explain can be much more impressive than accomplishments that are simply hard to do.

This is the secret of Steve. He’s not brilliant. super passionate, or ultra-hard working — instead, he accomplished something that’s hard to explain. This is why he is more impressive than David, even though his high school career required less time devoted to extracurricular activities.

“Stanford Doesn’t Take Students with B’s!”

To help cement this concept, let’s consider the story that inspired the title of this post…

In the late spring of 2004, Kara, a junior at an elite Bay Area private high school, felt nervous as she arrived for a meeting with her college counselor. Over the past three years, Kara had avoided the crush of competitive activities and AP courses that her peers suffered through to impress their reach schools. Even more galling to the hyper-competitive students at her school, she had even allowed the occasional B to creep onto her transcript.

(When her best friend tried to get Kara to drop a difficult linear algebra class, Kara, to her friend’s horror, simply shrugged and replied, “I like linear algebra.”)

“You’re on the cross country team, which is good,” the counselor began, when Kara sat down in her office. “But you’re not the president of any clubs, and with these grades, you’re just not going to get into your reach schools.”

Kara stammered a response, but was cut off: “Kara, Stanford doesn’t take students with B’s!”

This counselor, however, had not taken the failed simulation effect into account. It’s true that Kara had avoided an overloaded schedule, and in general enjoyed her high school experience. (“I was perceived as the relaxed kid at my high school,” Kara told me recently, grinning sheepishly as if admitting a crime. ) But her main activity, when described right, thwarts any attempt to be mentally simulated: she had developed a technology-based health curriculum that was adopted in ten states.

When you dig deeper, Kara’s path to this accomplishment was much like Steve’s — serendipitous occurrences developed, over time, into something inexplicable. But these details are irrelevant, because before you can ponder the reality of the story, the failed simulation effect has taken hold.

Indeed, in defiance of her counselor’s protestations, Kara did get accepted to Stanford — not to mention Columbia, Johns Hopkins, and MIT, where she now attends.

The Most Important Effect You’ve Never Heard Of

I devote an entire third of my new book to exploring the failed simulation effect. I also made it a cornerstone of Study Hack’s zen valedictorian philosophy. So it’s clear that I’m a huge believer in its power. This being said, it’s still fair to ask whether this neat abstract concept actually plays a role in real world admissions decisions.

To answer this question, I turned to Dr. Michele Hernandez. Dr. Hernandez is a former assistant dean of admissions at Dartmouth College and the author of the bestselling book, A is for Admission. She currently runs an elite college counseling service, and offers a popular 4-day application boot camp.

In other words, when it comes to figuring out what works in college admissions, Dr. Hernandez is the person to ask.

“College admissions officers are only human,” she told me. “If they stop to say to themselves as they read a file, ‘wow, I wonder how Nancy managed to do this,’ that will be a huge plus.”

Though the specific name, failed simulation effect, is new to Dr. Hernandez, the general concept is not: “In my private practice, I always push students to try something like this that will make them stand out. My most successful students are those that take me up on my offer.”

Such students, however, are surprisingly rare, and this is due to a thorny reality: it can be incredibly difficult to put this effect into practice.

A Simulated Catch-22

Like many students, your instinct on first hearing about the failed simulation effect was probably to think to yourself: “What could I do, like Steve or Kara, that will generate this same reaction?”

Unfortunately, the chances are slim that you’ll come up with a good answer.

Here’s why: If you’re able to think up an activity that will generate this effect, then, by definition, you were able to simulate the steps required to complete the activity — otherwise, it wouldn’t have come up as a possibility. If you’re able to simulate these steps, then it’s likely that other people could simulate them as well. The result: the activity will not generate the effect.

It’s a catch-22: if you can think up the activity, it won’t have the traits you need.

Fortunately, Steve’s story highlights an escape from this paradox.

The Insider Advantage

Sophomore-year Steve could not have woken up one morning and thought: “I got it! I’ll find a youth-focused sustainability organization and volunteer to work on their media outreach so I can earn a trip to a UN conference!”

But for junior-year Steve, who had already done work with the UN, leading him to meet a representative of SustainUS, this failed simulation effect-generating idea was completely natural.

The difference is that junior-year Steve had become an insider. We can generalize this observation into an effective strategy for finding similar projects:

- Choose a field.

If you have a deep interest, this makes the choice obvious, but don’t over think this decision: you don’t need some mythical perfect match with some equally mythical innate talents or passions — your interest will grow with your involvement. - Get your foot in the door.

Join a community; volunteer; attend a conference: whatever exposes you to the inside workings of the field - Pay your dues.

The more you exceed expectations, the quicker you’ll rise to insider status. - Once you’re an insider — and not before — seek projects with failed simulation effect potential.

If you start this search before your an insider, you’ll end up with generic ideas that are easily simulatable.

In other words, devote your energies towards becoming an insider and head-turning project possibilities will eventually come along for free.

Putting the Pieces Together

As you age, the failed simulation effect becomes less relevant. At its core is the surprising juxtaposition of an impressive accomplishment and the young age of its progenitor. When you’re 25, by contrast, and trying to craft a remarkable life, the failed simulation effect won’t save you from actually becoming really good at something rare and valuable.

But for a high school student, this effect can provide a strong foundation for building an impressive college application without living an overloaded lifestyle.

As mentioned, I devote an entire third of my new book to detailed case studies and step-by-step instructions for how to realistically integrate this advice into your life. If you’re serious about this philosophy, you might consider pre-ordering a copy. In the meantime, however, the ideas laid out in this article should be more than enough to get you started: quit the key club; ditch the expensive mission trip; drop the 5th and 6th AP course from your schedule; and put your attention toward becoming an insider.

Then once you’re on the inside, let the failed simulation effect lead you to an uncluttered, meaningful, and happy high school life.

(Photo by Luke Redmond)

Cal, what an insightful observation. When I read the two stories, I did exactly as you suggested – I held them up to the mirror and assessed a higher value for the accomplishment I couldn’t visualize myself achieving. As soon as you broke it down, the light immediately came on.

Recently I was admiring the achievements of the Intel Science Talent Search winners (see https://www.societyforscience.org/STS) and hoping that my daughters might achieve something at that level. But as you suggest, the challenge of pulling off an achievement of that magnitude is very daunting. While I figured that I would push them toward deep involvement where their interests lead them, I had not thought out the specifics of how to go about that. I will absolutely add the failed simulation effect to my list of techniques of inspiring and motivating them.

Great post as always, I’m going to pass this along to some of my students who are finishing off their applications. I’ve in essence communicated some of the same concepts to my students but not as succinctly and eloquently as this.

Where you able to get into some of the larger chains based on your pre-orders?

this is AWESOME

It’s interesting that you mention science fairs. I actually have a chapter in my new book where I take the awe-inspiring resumes of two Intel winners, then break down, step by step, the reality of their achievements — as it’s different — and somewhat less daunting — than most people assume.

Encouraging deep involvement with a small number of interests is an excellent strategy. I observed in my research that even simple things — discouraging cluttered extracurricular schedules, expressing admiration for figures who immersed themselves in a single field for the love of learning — can go a long way in this direction.

I’ll be in the larger chains. The question, however, is how many copies! (My red and yellow books are chronically sold out at Barnes and Nobles and Borders). The more I can sell over the next few months, the better launch we’ll have. I really appreciate all the support you’ve expressed already.

David’s story is boring, Steve’s less so. You do not need an experimental psychology to pin that down… (although you may need it to fill a third of a book with that 🙂

i’m sorry i think david is the more impressive one.

No knock on Steve, but I think the reason his achievements seem more impressive when summarized is that we’re pre-conditioned to be impressed by the UN itself. The perceived prestige of his accomplishments ties into the cachet of the organization. The rest seems like him taking advantage of lucky breaks — having been talking to the right nonprofit at the right time, having geographical proximity to the UN, and so on.

Where stuff that is particular to Steve comes in is that not every student would have taken advantage of those opportunities.

Great work again Cal, you keep raising the bar. 😉

Your definition of the failed simulation effect would be less ambiguous if you replaced “explain” with “account for.” Otherwise a natural reading is, “Achievements that are hard to describe…”, which isn’t what you mean.

“Boring” is a meaningless term in this context. When you start drilling down to get specific about what makes an activity “not boring,” you’ll find the task complicated by the same sort of issues that I describe in the article.

Columbia’s admissions staff disagrees (they reject tons of “David’s” each year).

An interesting suggestion.

Thanks for a great article! Minor edit: “your” vs “you’re” in the sentence “If you start this search before your an insider…”. Regards.

I have to be honest. I had two thoughts. The first is that these two snippets are way too little from which to draw a meaningful conclusion, and so I decided to go with a gut reaction. The second is since I went with my gut reaction, I thought that David was more impressive because he DID pass the simulation effect. For him, I knew exactly what it took to do what he did. For Steve, I had no idea, and so I just assumed that he probably got lucky or the event he was describing was described with enough spin on it to make you dizzy.

I was a Dave in high school (substituting robotics team for calligraphy). Luckily, I didn’t apply to Columbia. I did, however, get into a number of top tier institutions including Penn and Stanford. So I think you have to be careful here. The admissions councilors think very carefully about results of admitting different students. Although they will admit as many Steves as they can, each with equally unique and impressive sounding experiences, they still gladly admit students with standard and impressive credentials. The fact that you mention that Columbia rejects “tons of ‘David’s'[sic] each year,” has more to do with the fact that there are overwhelmingly more applicants like David than there are like Steve. They may find the few Davids that they do admit to be equally as impressive as the Steves they admit.

I am a well respected member of my profession, I am often asked to save failing projects. I lead teams of people turn around multimillion dollar failures into collosal career saving wins. My oldest child of 3 will graduate highschool next year. My wife of 17 years and I have a wonderful happy family. I am only 37. I disagree with you on how the failed simulation effect loses it’s weight as you get older. The story changes and the rewards aren’t as big. Oh yeah, I don’t have a college degree either, but that is a different topic.

Money + Luck = More Opportunity!

(assuming Steve’s parents are carrying him.)

An alternative would be to apply to a university in the UK, Canada or Australia where extracurricular activities are meaningless.

Great post Cal!

This is a non-trivial insight.

It reminded me of this comment on Feynamn:

“There are two kinds of geniuses: the ‘ordinary’ and the ‘magicians’. An ordinary genius is a fellow whom you and I would be just as good as, if we were only many times better. There is no mystery as to how his mind works. Once we understand what they’ve done, we feel certain that we, too, could have done it. It is different with the magicians. Even after we understand what they have done it is completely dark. Richard Feynman is a magician of the highest calibre.” – Mark Kac

Great post, Cal.

I love this post Cal. It has really inspired me to become an insider and get involved in something that I love!

I have a question though. I play a varsity sport and have been playing in a state orchestra for the past three years. What troubles me is that I see all sorts of similarities between Dave and I. I am currently a junior in high school, so I feel like time is running out too. Should “Daves” like me continue with the “sports, grades etc.” or abandon them to become an insider?

What’s your advice?

This post is comforting for me, as a high school sophomore suffering a disastrous year. But how can you apply the failed simulation effect to writing? The only thing I could think of that the majority would be impressed with is writing a book in high school, or publishing in a magazine such as the New Yorker (and I am uncertain if this is possible for a high schooler). There is no equivalent, as far as I can tell, to writing a technology-based curriculum for several states.

Cheers!

I enjoyed the article, but at the end of it, I found myself thinking, “Oh wait, did I just read 5000 words which basically are a re-packaging of the very familiar concept of the “wow, how’d he do that?”-reaction?”.

Hey Cal, I really really enjoyed this post. Great job!

@Daniel

Do what you love. This comes across to admissions councilors much more than leveraging your activities for the best affect. Part of he point this guy makes is that the people who become insiders do so because they find something that they love to do (or at least interests them enough to pursue it). They are not trying to manipulate or trick their way into a good college.

You should continue to do as well in school as you can and pursue the activities you enjoy. To be perfectly honest, no matter how hard you try, you likely won’t become an insider if you’re just doing an activity for the sake of becoming an insider.

This was an excellent story. This is covered in more detail in your new book?

The University of Ohio? I’m not sure anyone in human history has been a professor at that non-existent institution. Ohio University, on the other hand, has been around since 1804.

Trying Failed Simulation effect is a good strategy to join a great college and it is good for teachers as they get an interesting student. But does such a student perform well in the great college? Has he ‘really’ learnt how to work hard and excel? or will he just be successful by relying on randomness?

What wonderful work, Cal. You are doing justice to your mission “demystify sustainable success”. Note also that “the insider advantage” explains most of the “miracles” that human beings were capable of. Ex. Jesus and Buddha proposing a new morality, Michelangelo painting the divine, Einstein redefining how the universe gravitates, Chico Xavier becoming Brazilian icon with charitable services, they all became insiders befor proposing their best ideas.

I also believe that it is not necessary to want to be a super star to implement these ideas. For all that we can turn our minds, we will come out best by first submitting ourselves to experience and then adapt theories to facts and not the reverse, as suggested Sherlock Holmes ;D.

PS: Cal Newport is working on Demystifying Sustainable Success for years and since he noticed the “confounding effect” he is helping us to deal with it. He also claims that noticing “The Failed Simulation Effect” was natural and this why we find it a masterpiece.

Best,

Hi I’m just wondering, to what grade is your newest book written? Is it good for juniors and seniors? or is it best for freshman and sophomores?

Curious, Cal.. How did you become an MIT star when you don’t seem to do extracurriculars? What part of your app got you into MIT?

The level you’ve reached with your education amazes me.

Great post Cal. Your insight into this area is eye opening. While reading your post it reminded me of (Dr.) Farrah Gray an improvised south side Chicago youth determined on becoming a CEO of his own company. He accomplished this, sold the company and became a self-made millionaire at the age of 14. The “failed simulation effect” really resonated with his success and the steps to building an “insider’s advantage” are evident in his story. He entered a field that he was deeply interested in: helping economically challenged youth and combing it with leadership and entrepreneurial instinct. As a result he got his foot in the door by co-finding a club in Chicago that helped educate “at-risk” youth in ways of obtaining money legally. He continued by sitting on advisory boards and doing a television and radio simulcast. By paying his dues he ended up with a flagship office on Wall Street and after an interview at the age of 11 got national recognition through mainstream media. Years following he began several other youth oriented business ventures that were quite successful. Consequently, he started foundations to keep giving back, speaks around the country and was awarded an honorary doctorate degree from Allen University. Though he is an exception and already has a doctorate he would certainly make an outstanding applicant for another degree. Dr. Gray created a mind boggling failed simulation; for many, their pre-teen youth is hardly comparable in terms of accomplishment let alone their high school career. All his accomplishments lead Donny Deutsch to say in an interview with him that he was the “most impressive guy” he’s met.

Right, but that would still indicate that you’re better off being a “Steve” than a “David” in terms of maximizing your college options.

That’s actually very heartening to hear. Can you provide us more details about what the FSE might look like post-college?

What a great quote. I’m going to use that.

I wouldn’t abandon long-term investments at this stage, especially if they provide you with real tangible benefits in your life. This shouldn’t stop you, however, from finding a new area to start building an insider status.

Oh no! This is exactly the type of brainstorming I warned you not to do! That’s the point of the article, if you could think it up now, it’s not going to generate the effect. You need to find a way to become a writing insider — some organization or community you can get involved in that requires writing and rewards ability. Pay your dues there before looking for your FSE opportunities.

The last third of the book is dedicated to the topic. I walk through the science behind it, then provide some more concrete rules for how to generate it in your own life, then walk through three detailed case studies to show what those rules look like in practice.

The unspoken rule behind any admissions advice is that it’s assumed that your grades and test scores are within the median 50% of accepted students. If you’re below that, your activities don’t matter. If you’re in that range, then you’re going to do fine — academically — at the school. The real trick is how to stand out from all of the other students who will do fine. That’s where phenomenons like the FSE come into play.

Definitely. It’s really at the heart of my last article, on Professor McLurkin, as well. There’s something crucial to gaining knowledge before doing something that catches people’s attention.

The book is applicable for all four years. Actually, I’d like to think that it’s applicable to anyone interested in understanding the science behind being interesting, and how to leverage it to transform yourself into a more interesting person.

I went to MIT for graduate school. In graduate school admissions, your extracurriculars are meaningless. All that matters is your ability in the field and your proven ability to do high-level research. This is sort of a general theme for achievement beyond college: put in the time to get good at something valuable — that’s what matters.

I know of Farrah (I read “Realionaire” when it first came out). I agree that he’s an excellent example of the FSE at play. (Though I don’t think he refer to himself as “Dr.”, as this isn’t usually standard for honorary degrees.)

Hi – sorry to spam this post – I was just wondering how long it generally takes to respond to emails? I really need your advice on something but don’t want to spam your inbox if it’s 2-3 weeks; as the need for advice will have changed. Thanks. J

For e-mails from students, around 1 – 2 weeks. For other e-mails, around infinity weeks. If you leave your question as a comment, you’ll probably get a response sooner.

Very interesting post and analysis. However, I think there may be a simpler explanation (excuse me if someone in the comments already suggested it): Steve’s activity focused OUTSIDE HIMSELF. He was doing something that benefited the world. David’s accomplishments were essentially self-centered (not meaning they were selfish, merely that they were entertaining for himself rather than beneficial for others). I was impressed because Steve’s efforts indicated values I agreed with (which is my own bias that I need to be careful about).

That hypothesis would predict that students who spend a lot of time volunteering — say at their church, or local hospital — would have a big advantage in admissions. But they don’t. These activities are focused outside themselves, but they don’t generate the failed simulation effect.

Firstly Steve enjoy working public, volunteering and he found his talent , natural talent at that time .

And he’d hard worked that time because he love it.

In conclusion: I think we should go outside safe zone, join in public activities, through them we’ll find our true talent.

This article is fascinating!

There’s just one problem: On the Common Application, there isn’t much room to describe the projects in detail. If I “designed a technology-based curriculum recently adopted by several states”, I would have to write Internship at a Technology Company instead. I can still attach a resume but the reader would obviously be able to simulate the steps that led to the achievement. Is there any way to get around this?

Thanks!

Let me push back here a little bit. First, as I pointed out above, I don’t see any amazing natural talent being displayed in Steve’s story. Second, the amount of hard work he expended was significantly less than David.

This comes back to the observation that the failed simulation effect is responsible for a bulk of the impressiveness you feel.

I never used the Common App, but the solution seems obvious to me – just write about your surprise project in one of your application essays. It should be the most interesting thing you have to write about if you follow the zen valedictorian strategy here, and i doubt that most admissions officers take more than a cursory look at the list of ECs anyway. At schools like UChicago your essays are king.

I’d have found this more interesting if the situations between Dave and Steve had been more comparable. You’re comparing someone with business and international experience to someone who has run a track team. Sorry, but the guy who can interact maturely enough to fool UN officials is way more impressive than the guy who pursues Japanese calligraphy through sheer practicality.

This is the tricky part of the failed simulation effect: it makes a student seem so obviously impressive that your instinct is that it’s obviously explainable. But when you look closer, the explanations falter.

Let’s take your explanation for a ride. You say the key is that Steve “interacted maturely enough to fool UN officials.”

I could contrive other activities that required quite a bit of maturity, for example, sitting on the elder council of your local church, or running a large charity event that required sponsors, etc. Neither of these examples are as impressive as Steve.

The difference: failed simulation.

I still disagree. Any position that requires a person to interact with international lobbying delegates with real power has a lot more pressure than with a church council. To me, what’s impressive about Steve is that he has experience in business situations with relevance to real world issues that can take him places after college, whereas Dave is going to have a tough time finding a place for track and calligraphy in a professional setting.

Please Anna, allow me to enter your conversation. But

is not as limited as you think. Take, for example, the Brazilian “idol” Chico Xavier, what he did was only write (psychograph) books and give food to people. But he did it in such a massive way and letting so few to himself that even this simple work could impress the world. He had been suggested to the Nobel and so on.

I mean, he did church council work, but took it to a worldwide relevant level. It’s hard to imagine how he did it and we can only repeat their results if we become really committed insiders in the charitable services. (And this is how it links to deliberate practice, loving what you do, develop discipline…). I think we can also imagine David using calligraphy to promote peace, love and education in a relevant leval, but he faild to use what he loves to do all possible good.

You keep changing your assessment of what makes someone impressive. Let’s try this new idea: “experience in business situations with relevance to real world issues.” A student with a serious corporate internship would have more high pressure exposure to relevant business situations than Steve. Yet we’re not nearly as impressed by the student who maintains a hard internship.

To come back to my main point: The failed simulation effect is what remains when you begin systematically testing the various ideas that might pop to your head about why certain students impress us.

Yes, please. Do provide details!! If I understand Cal correctly, this article is solely intended for high-schoolers trying to get into elite colleges rather than to people trying to get a job or get into grad school.

Actually, tucked inside this quote is a really interesting point which I will definitely think about some more: are certain extra-curricular activities considered more “valuable” than others? If so, what criteria can we use to weed out more valuable activities from less valuable ones?

This reminds of two references:

1. The following quote from Thomas Jefferson: “I’m a great believer in luck and I find the harder I work, the more I have of it”

2. The Bill Gates story from Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers: Gladwell mentions how Gates had access to certain computer technology at the University of Washington that most people didn’t have access to back in the early days of computers, which allowed him to get many hours of programming experience long before he dropped out of college.

This does seem like a good point. I’ve heard some of my fellow undergraduates talking about certain activities as having more “prestigue” than others. The last thing I heard described as having “prestigue” was something called the Diversity Summer Internship Program. Judging from the mention of “diversity” in the title, I’d say that the “prestigue factor” has to do with how closely it conforms to some contemporary political agenda.

i LOVE this post, but once I got to thinking about it, I know you said that kids can’t set out -trying- to do something spectacular, but I really feel like the activities I could have turned into something big didn’t have a higher level to get to, or the fact that I’m in a public school in a small town may have limited me.

I took every opportunity to be involved in my school district’s education committees and programs, was the only student on two district-wide teams, and created a workshop for 4th and 5th graders to present to every classroom during my study halls. I designed a logo for the district that’s everywhere now, but I don’t think there was much more I could do. It’s not like they would let a kid on the Board of Education, no matter how many great ideas I had or how much drive I had to complete every project.

The other thing that I was hoping would develop into something bigger would by my involvement with classical & contemporary Indian dance. I live by a city (not too big, though) that has a significant Indian population. I’ve worked with the same dance teacher since I was 5, developed a close relationship with her, had the best graduation performance in the history of the dance school, and went on to choreograph over 5 dances and teach my own group of beginner dancers for 2 years. The problem is, almost every Indian girl who applies to college does some sort of dance, and I worried that the people who worked in admissions wouldn’t realize that I had more creativity, diligence, and talent than a good chunk of those girls. And the core problem was the same as my problem in the last post: there was no where higher that I could go. There was no dance team I could join, no professionals who I could work with, it wasn’t NYC, Boston, or NJ where loads of Indian people would be there and I may have more performance opportunities. We only performed as a group, and I had very little I could do to make this something more.

I recently found out that I was rejected from harvard, yale, mit, columbia, and brown. I know that my academic credentials were not as amazing as they could have been, but i’ve taken a total of 8 AP classes, am #8/334 in my class in a respectable public school, and have a 2330 on the SAT. If either of my interests in education or indian dance had something more that I could aspire to and achieve, maybe I would have been accepted.

I know it’s useless now, but what exactly can one do in a more rural area?

I’m not so sure that the rank ordering matters. So long as their is a sufficiently sized market for your skill, you will gain “capital” you can cash in.

I definitely think this has some practicality beyond college applications.

I’m a law student, about to graduate. I am interested in family law, which a lot of places don’t practice. Those who do practice it focus on it. So there’s a very specific set of employers. At my school, my class was required to complete the intro class for family law, and 2 additional classes are offered (there’s another that is arguably useful, as well). I’ve taken 2 out of 4.

But I’ve also worked at a family law firm, interned for a family law judge, and have been involved with a family law specific research project (that I was approached by a professor and asked to help with!).

However, none of those has helped me as much as becoming a member of my local county bar’s family court committee and women lawyer’s group. Attending those meetings has given me insight about who’s hiring and what they’re looking for, as well as what issues are being faced by family court lawyers in this area right now. I am able to have intelligent conversations (and form opinions!) about issues that many of my classmates are not even aware of.

My point: even if there aren’t many ways to differentiate yourself initially, by becoming an insider you may learn more about what is important to members of the profession so you can better highlight how you fit their criteria.

“An alternative would be to apply to a university in the UK, Canada or Australia where extracurricular activities are meaningless.”

I have to completely disagree about the UK, I’ll be applying for university here this Autumn. While Oxford and Cambridge both say they only want academic excellence, most of the other top universities take extra curriculars into account. Where I think we differ from the US is that doing extra things doesn’t count for that much (though they do get a few lines in your personal statement) unless it’s related to your subject. Since you apply straight away for your “major”, universities expect to see a deep interest in it in your application- for example, my best friend is applying for English, so she’s joint editor of our school paper, she enters poetry competitions, she helps teach younger students how to read, etc. A whole lot of students get three As at A level, so it’s important to stand out in other ways.

Interesting post though! I have an opportunity coming up that might help me gain some insider status, so I’ll have to see how that goes.

Steve sounds like those anoying teachers pets who would do playlets about “issues” at assembly.

This is a great post! 🙂

But I am a college student already. Could you talk about how to get into the best grad. schools? Like I want to go to Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Can I email you if I have some other personal questions regarding college success?

Thank you Cal.

Great article!

Coming from a cognitive science/psych background, I really believe in the “pervasive tendency…to use the self as a standard of comparison in [our] dispassionate judgments of others.”

I run an admissions/writing consulting company and face this issue with applicants all the time. However, I would also make the case that while the psychology of impressiveness is always at play, the psychology of authenticity is equally important. A student that is the star of the track team may have an edge on the student that founded the non-profit if he/she can write with a voice or angle that is refreshing, bold, and authentic. The more admissions officers read about over-packaged, over-groomed applicants, the more they simply seek real people. Students with a point of view, and not an admissions ulterior motive.

I see your point completely. Just want to stand up for the overstretched track team captain to let him/her know, point of view still means something–and the human admissions officers are still responsive to ‘old stories’ told in a new, passionate, unabashedly authentic way.

Great blog!!!

Janson

Ivy Eyes Editing

http://www.ivyeyesediting.com

http://www.ivyeyesediting.com

Great article, Cal! I feel very inspired to do the things I always wanted to do. I do have B’s in my transcript (though most of them are in PE and one in academical subject). Personally, I had to wage a war against myself; as an Indian girl, I was “conditioned” to do something admissions officers will love; however, I felt bored and unhappy with my life.

Now, I do extracurriculars which I have a high interest in. I volunteer as a camp staff for little kids, in a museam as well as the library, not because I want to amass hours. I am also involved in my school’s theatrical arts department although I am a math-science type of person who wants to major in engineering physics. I have also developed a leadership program and a month-long entreprenuership simulation that enables students to be familierized with the start-up process. And all this at the expense of throwing away classical music, which I did not very much like at all.

I’ve got to disagree a little bit here. What struck me most about Steve’s essay as opposed to David’s was the scope of the accomplishment (perhaps only in addition to asking myself if I could do that and what it would require). The scope of Steve’s accomplishment is Global (there is only one UN) while the scope of David’s is local (there is a track team at every school and, presumably, a captain of every track team).

Hi Cal,

I am a junior in high school who lived as a stressed student from an overload of activities my freshman and sophmore years. Now I am in many fewer activities, but feel as of I wasted those years. I feel as of there was no point to those activities if I am not going to lost them in my college apps. The only activities i kept with are my church choir, a book club, and possibly soccer in the winter. I am not sure if i should pursue this activity since i am not a high candidate for the role of team captain.I have many interests and am involved in different communities, but I am not sure how to go about asking for a more “insider” project. Please bestow me with your genious advise!

P.s. Please forgive my grammar and punctuation errors above; I am writing from my touch and am not the best typer in the world in this apparatus.

You *have* to read my new book, especially part 3. Even if you camp out in B&N and read it in the cafe, still make sure you read it. Your answers are there…

grest post… i started my high school search since the 9th grade and I’m currently in the 11th grade. i totally agree with you on the simulted catch -22. i want to get into stanford university, but my extracurricular activities are not so strong.. my question is how do i begin something like what steve did in the engineering or business field?

the thing id that i i think of something i can do that toally defeats the purpose of the simulated catch-22… What do you recommend? where should i begin? what type of organizations should I be “in” to get that powerful application?

Start with the four step process I lay out in the post. From there, you can get more details in my recent book.

Hi,

Im an international student who really wants to get admission in stanford undergraduate. In my country, we have the british a and o levels, so how many subjects would you recommend for a good chance in stanford? And, there’s limited opportunity for me for what i can do extra curricular wise, i have participated in MUN’s as i love to debate, and i was the captain and vice captain of my school basketball team. Do you have any suggestions as to how i can improve my extra curricular activities?

Thanks!

Hmm. So, I’m like, completely devastated by this post. I might as well be wearing a name tag that says “Hi, my name is Dave!” Wow, I’ve screwed myself over with hard work for the last four years. Anyone could pull off a load of AP courses, extra curriculars, fundraising, work and volunteering. Its all… feasible for anyone who “tries”.

I sincerely hope college admissions officers, especially at top-tier schools are smarter than you give them credit and are able to see past the “OMGWOW” factor. In your comparison at least, I feel Dave is superior to Steve, not only because I am like him. You explicitly state that he is more talented, and more hard working. Steve has only what falls under the category of “intriguing life experience”.

I was personally taught the key to success was hard work. I never had any huge opportunities that would land me in the UN or anywhere else, and neither did any of my fellow Daves. I took the little local ones I could, and sincerely enjoyed and worked hard on each one. Hard work and talent are worth a lot more than any big lucky break. Without that lucky break, Steve would be worth less than any Dave.

My initial reaction was that David was more impressive, because the calligraphy is unusual, and it made me wonder what kind of intriguing person he might be.

After reading these posts, and Cal’s ideas, I would like to say that I think the difference is, that the way these two young men’s accomplishments are described, it would seem that Steve’s activities expand and deepen, while David’s are more static. In other words, if David had also experienced serendipity, perhaps his calligraphy teacher would have also involved him in a study of Zen Buddhism, or perhaps David would have gotten into teaching calligraphy to kids in the city, or illustrated a book…

The irony is that, for me, it is exactly that he stuck with calligraphy for 4 years, without doing this other stuff, that was impressive. It speaks to self-discipline, humility, patience and perseverance:an ability to pursue something with an eye to perfecting it overtime, something that is relatively rare in our impatient culture. David is very “zen”!

I think parents can help their kids by helping them find the meandering path of interest that can help foster experiences like Steve’s. But I agree with others that it is much better if this “wise wandering” (a term I love) is driven by genuine interest and not ambitions for college.

And congratulations to those students who remain relaxed and enjoy these pursuits for their own sake, and to the girl who didn’t care about getting a lesser grade while taking the linear algebra that she loved! These are the kids how have not only the most satisfying experience at college,but the healthiest, emotionally. The point is the journey, not the destination, as they say.

It’s an interesting idea, but I find Steve’s and Kara’s stories more convincing than David’s not because of failed simulation, but because they accomplished something that mattered to the wider world. While it’s very nice to master calligraphy and to perform well in sports, it doesn’t actually benefit society much. David and Kara made genuine, lasting contributions to the world outside high school.

As one who has been involved in several UN and WHO “initiatives” – let me dissuade you of the misconception that the UN actually accomplishes anything in the REAL wider world. My experiences have taught me that 99.99 percent of what goes on at or via the auspices of the UN is completely worthless word merchantry that ultimately accomplishes nothing. You may as well stay home and masturbate than waste time on a UN-related project or initiative, unless you judge that simply going through the form of talking and debating, then producing reports that are circular filed and are entirely futile endeavors is nonetheless somehow productive. I judged it to be a complete waste of time after several UN/WHO adventures I was involved in.

It seems to me that Steve’s credentials at the UN came from pure chance. While reading Dave’s story, chance was not on my mind when I thought “How did he do this?” Steve managed to be at the right place at the right time. What happened if he was 1 hour late? Would he have gotten to where he was now? These questions leave me wondering, and not in a good way. Just food for thought.

Remember, however, if you’re an admissions officer, you don’t know the details of the story of how he got started, you’re only encountering the final result: the fact he did this work with an NGO and the UN.

What do you think my chances are like of getting into Stanford? I medaled at an international business competition, medaled at a national science fair competition, has been a competitive swimmer for the past 7 years and has medaled at a provincial competition representing my school. I also am the president of my school’s athletic council, an executive on the business club, mentor for a Kid’s Club and am a strong devotee to the practice of yoga. I’m in the Ib program and have a 95 average this year, but in the previous years, it was low 90s/borderline high 80s.

Steve story is like getting a “game ball” in the little

league. When a no hitter touches a ball that is unusual and he gets

attention. Unfortunately society has lost objectivity a long time

back.

Loved the article. But I am still confused – what is “B” possessing?

Straight from the horse’s mouth. As quoted from Stanford’s website, “Merely being involved in many clubs is not what is most important; your depth of commitment in whatever you do interests us the most.”

Thank you for the article on the failed simulation effect. It challenges conventional thinking on what it takes to succeed in college and in life. Congrats on a job well done.

Ha ha the url of this blog is funny 🙂

how-to-get-into-stanford-with-bs-on-your-transcript

Carl, the last bit on being young is really insightful.

I just turned 21..and I’m already in my 2nd year in the University, would you consider me old to launch into the failed stimulation test?

When I read the descriptions both sounded equally impressive to me. Then I read your text and realized that my reaction confirmed your point — I work in international development; from my perspective landing a UN job is neat but on a par with the track captain experience. Like one of the first commenters, I was more impressed when I heard Steve’s detailed story. I had originally assumed he got the internship through family connections.

so does getting around all Bs in one semester of sophomore year classes just deny you acceptance into reach colleges? because i have all As in my 4 ap classes this year both semesters, and i have no Bs except for my first semester in sophomore year. that was the only semester i got Bs, and they were all accelerated courses

Stumbled upon this blog and just have to comment. The posters here have completely lost sight of reality. What do you think getting into Cal Tech or Stanford will buy you in the long run? My parents and some grandparents all graduated from Stanford. They are not particularly richer or happier than their friends who graduated from University of Oregon or Montana State. They take pride in their college achievement, of course, and have a good life but never pressured me to do the same. I was expected to get very good grades and be involved in high school and get a college degree but not at the expense of my health and sanity.

Great article – leveraging social comparison.

I can’t speak for Cal, but it seems to me now is the perfect time for you to launch FSE 2.0. Getting into undergrad school is behind you, but admission to grad school or launching your career is just around the corner.

But, the key difference now is that you need to focus on becoming an insider in the field you want to move into. That way, you develop high competence in your target field and, hopefully, parlay that into a failed simulation effect unique to your field. The goal now if for you to stand out from all of the other (very smart) college grads who will be applying for the same positions with the same companies or grad schools.

The first step out of undergraduate college is, in many ways, like the first step out of high school. The only difference is the forms you submit now called a “resume” and “job interview” rather than “college application” and “essay”.

[The other difference is that the people you meet while you become an Insider will be the ones who provide references rather than your teachers… and, they may be the one who points you to a job opening that is not advertised through the placement office). So all the more reason to simply start down the ‘insider path’ and then let the FSE take root.]

“Once you’re an insider — and not before – seek projects with failed simulation effect potential.”

Unrelated to the topic, but quite interesting nonetheless.

How does one short-circuit a wide range of Artificial General Intelligences used on the planetary energy farms?

Simply — pique AGIs ‘interest’ by producing consistent stream of ‘simulation-failing events’.

This (consistent) failure to regulate processes on the farm will (gradually, but inevitably) change AGIs priority from that of energy control to the one of information control. And, as we all know well, information is much harder to control… nay, information is impossible to control. 🙂

However, there is an unpleasant side effect of this turning process. The AGI will eventually run out of suitable ‘simulation-failing sources’ (that is, out of inventive people), and will have to subject its… subjects… to extreme conditions in order to extract from them the last possible drops of useful information. Life-destroying conditions are most useful in this regard because, as we all know, self-preservation is the strongest of natural impulses, and innovation blossoms in times of dire need.

Thus, sacrificing the whole farm is surprisingly common AGI decision.

Amazing post, filled with the best information ever I wish I learned even a year ago. Crack time for university applications are coming up in less than a month and I only wish I could have had the chance to make something special happen. Thank you for this — perhaps I’ll let my brother, an intense robotics and computer nerd, know, and hope that he can have the same situation as Kara.

Considering this post now has upwards of 10,000 unique views, its not such a secret trick now, is it? Funnily enough, it still works.

The common factor of the two success stories seems to be: admission or acceptance at the national or international level.

To be honest, neither one impressed me in any way, shape, or form. I considered both to be nothing more than self serving and typical college applicant with package-peanut filler type “accomplishments.” Maybe if one of the applicants did a few tours in the mountains of Afghanistan, I might be more inclined to take a closer look. In that case, he would at least understand the true nature of the world we live in and not be another cookie cutter politician playing a role in the UN’s puppet show. I would have burned his application just for mentioning “climate change.” A higher education shouldn’t be about political motives but rather the journey and search for truth. We don’t need any more “skull” members creating secret organizations that “do not exist” for the purpose of leading the herd. Marketing = sales = the type of work I did pre-college graduate at the local shopping center. The product doesn’t matter because the rules of marketing remain the same. So Steve is looking rather flat and predictable to me. David on the other hand learned calligraphy; so either he is a hopeless romantic who still believes in pen and paper or someone from his family is completely disconnected with the social realities of today’s youth and thought a calligraphy pen-set from Micheal’s would make a great Christmas Gift…although this is merely speculation. He could have in fact been Jewish, so it would have been one of the gifts from the 8 nights of gift giving. Either way, rather than let the thing collect dust in the darkest corner of the garage, he actually invested effort to make use of the kit. So, in conclusion, I have to give him credit for that.

Hello Cal,

Thanks for the highly insightful post. I am currently a high school freshman/sophomore who plans on becoming an environmental engineer. I have a question: how do I know when I’ve become an insider? This year, I started a project in my school’s environmental club that highlighted the detrimental effects of dolphin captivity. We organized a flash mob at a mall and filmed a video that won first place for its age group at a youth film festival. This summer, I have an internship at a local NGO that starts in two days. Is now the time to start brainstorming for failed-simulation projects?

Hi Cal, I am going to be a junior soon. I was just offered to apply for a job as a “social media correspondent” for Zinch. I just stumbled upon it. I wanted to know if that is more interesting than David’s activities? Is it impressive? I’m not doing it for passion, i’m trying it to see where it goes and to get paid.

wish I’d read this when I was in my teens! Any advice for the over 30s?

Insider’ job is something a normal teenager doesn’t do? So how can one can a job like that? Especially when I live in a suburban neighborhood and not the City.

Sorry, I’d want to know what their SAT scores are.

You can get into any school with a B average and SATs that are 2400.

I’m in high school now and like many of my peers I’m already worrying about the college application process. I’ve recently read your book How to Be a High School Superstar and it offers so great advice, but you often provide a vague explanation for how these students get these opportunities, saying they “stumble” upon it. I don’t understand how I can do great things like these students when I don’t have the luck to “stumble” upon such great opportunities. What I really have trouble with is the initial procuring of an opportunity. If you have any a dive, it would be greatly appreciated! Thank you!

Seems like a much more fair way would be to just admit people based strictly on SAT scores. It is meritorius and gives everyone an equal chance. In the end, as you pointed out recently Cal, all these “interesting” kids become either lawyers, doctors, management consultants, or investment bankers so it’s not like these elite colleges are pumping out “interesting” kids who will transform the world.

That’s a terrible idea. Do you have any idea of the controversy surroundig the SAT as well as the ACT? There are brilliant students with learning disorders, testing anxiety, and low socio-economic status who would be totally shunned if we used SAT scores as the sole admittance factor. They would likely need the high quality education they would receive more then the white males that are statistically more likely to do better, especially if their parents are wealthy enough to pay for tutoring for that perfect score. The SAT is actually considered one of the worst predictors of academic performance and success later on in life, and is far from fair and ‘equal’ in any way, shape, or form.

I’m currently a junior in high school. I really want to go to Stanford; however I haven’t really developed any insider status for anything. I am interested in pursuing medicine, so I have volunteered at a local hospital and I also worked with clinical trials business.

I am deeply involved in science fair and business club and I have won awards at the state level. But I have not placed at nationals….

What do you think my chances are of getting accepted to Stanford?

I live in Africa, Ghana and there arent many opprtunities for me to be innovative and use my resources, at least the little I have. I want to attend Yale University on a full scholarship, a far fetched dream I have been told, but my average grades and never really having done something outstanding in my life impairs me. Are there any programmes available that would enable me, a passionate aspiring International Human rights lawyer to reach my full potential,like Steve?

Here’s one more thing – the UN group thought Steve was a worthwhile intern. David’s work may have been intense or quirky too, and yes, the athletic position he held was probably more work than what Steve was doing. But David’s work was all in school. Steve didn’t just get validated by a school, where he was amongst high schoolers – he was validated by professionals that had nothing to do with high schoolers. That says a lot.

I like most of the messages in Newport’s books. It seems to me that the most important is that students delve deeply into an area that interests them. That is a good message for life. Colleges will figure out who they want to accept. The bulk of students at the most “elite” schools have the As and good backstories. For top schools, they are standouts for some reason or other. Mimicry or relying on some guide to pattern yourself after is not a very good idea-even if the guide is filled with good ideas. If you buy this book as a high school freshman, you are doing it wrong-high school, that is. High school is not just prep for getting into college. it is a time span equal to the time you will be in college. So, the best way to get the most out of high school is to consider those four years to be as important as college-in the sense of involving yourself fully in important activities and being fully engaged in being a high school student. Don’t consider your involvement in terms of college admissions, consider your involvement in terms of its value to you. Chris Peterson, from MIT, has an often cited article that is worth a read. Many of the points are consistent with Newport’s books-https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/applying_sideways

When I first read this I didn’t know what UN or NGO meant, so when I saw the descriptions I found David to be more impressive. After looking into it I feel that Steve is only seen as the more impressive one because people perceive the UN to be a really great thing.

Anyway, I think that the athlete is usually more impressive

Thanks for sharing an insightful justification. Steve is impressive because his clarity is deep and profound… and this is important because focus matters (especially when one is dealing with personal statement for college). I think impression is directly related to expression; your expression will compliment the interpretation and perception of others. Well, I couldn’t agree more, this article is brilliant and complete in itself 🙂

Oh no! My application to UC Davis sounds like a David! I hope I get accepted.

Fantastic article.

One thing I think is missed in the article though is the big differences in intellect between various people. For example, I believe it is possible for, say a student, to think up of something that an admission officer would say “wow how did he/she do that?”, even though the student actually had it planned out before.

So I actually did all of this – I founded a nonprofit at 15, brought it to help almost half a million people by age 17. I applied to Stanford EARLY ACTION when I was 18, visited the campus, attended a lecture, did a kickass interview. Oh, and my SAT scores were in the 95+ percentile. I also was an AP scholar with honor… then an ap scholar with distinction.

The ONLY thing dragging me down was my transcript. weight was 4.2, uw was 3.5.

And you know what? Flat out rejected.

I noticed a few kids asking fearfully if having had some Bs on their record will prevent them from getting into a good college, even if they have all this other cool stuff to talk about.

I just wanted to say some encouraging words to them.

When I was a kid, I was such an over-achiever my parents were worried that I would work myself sick (Not an invalid fear — I had done it before). So in high school, they made me SWEAR to get one B per semester. If I brought home straight A’s, that was rewarded far less than a transcript with a B on it. I kept my promise and for all four years of high school, I got less than straight As. I still got into every fancy college I applied for anyway because I was able to put unusual accomplishments on my application.

Another anecdote: My father routinely *failed* classes in high school, not because he was dumb, but because he was bored. He was accepted to (and attended) MIT based on the electronics and physics knowledge he self-taught and applied in his basement (while not doing his homework).

Many colleges say on their websites or in their admission materials that they are less interested in your grades and more interested in your “commitment” or “insight”. They aren’t saying that to trick you! Your grades are not the only thing that define you, either for college or for life, no matter how much it seems like it when you’re in the thick of it!

Brilliant ideas. Awesome advice to get in statford

You are a very strong story teller my friend.

I will definitely use this piece of information as I apply for Law School at the end of the year. Keep up the passion, it’s much appreciated when reading your words.

I’m worries that the article doesn’t address the gap in opportunities connected with sociology economic status. While there are anecdotes that have kids from lower class standing doing spectacular things, it’s difficult to become an insider when you have to get an after school job or your family is cutting it pretty close on basic needs. I think the emphasis on the unusual insider gig perpetuates a classism enshrined in the college admissions process as it is today. It also relies on parental finding and connections– something you might not have if your parents are tradespeople or work in retail. It strikes me as an unjust standard that rewards those who have the best social and economic resources.

Ahh! Posting from a phone. Sorry for typos. worries=worried, finding=funding.

There’ s something you neglect to explain: the essays. I hope colleges like Stanford know that opportunities like these that “make you an insider” are at least 70% a fluke/a stroke of luck. It’s simply you finding an opportunity cropping up, and seizing it. If all colleges only admit people like ol’ Stevie there, they’ll have nothing but “lucky” students attending…and they don’t even know whether that stroke of luck will last. Colleges need to see your personality, and from there, they can deduce whether your character and drive can produce something good for them in the end. What better way to do that than through essays? Don’t get me wrong; it’s good to have these “achievements” under your belt. However, if those achievements came by strokes of luck, then they really shouldn’t be achievements at all. Besides, there are also a ton of people who get admitted who have NOT done anything brilliant; they expressed their creativity and uniqueness through their essays and got good grades. Really simple. There are other factors, like if the admissions officer who read your essay had lunch already. I’ve heard numerous people get in because they added this one interest that compelled Stanford, like “playing DDR” or forming a “lunch club.” I think it’s less the probably lucky accomplishments you have under your belt and more if you have the character and visionary mentality to get you far. Your argument is very sound. However, is it generalizable to everyone? Even at least the majority of applicants? No.

Also, that important word crops up yet again: LUCK. Everyone, even the David’s have a chance. It’s just those little random factors like random errors in a science experiment that decide whether you’re accepted or not. Truly, admissions is based on luck moreso than anything. Even being an insider.

I go to Stanford. From my experience, Dave looks a lot more like a typical Stanford student than Steve does. Steve sounds more impressive to the average person than Dave but not to an Admissions officer at Stanford. How many people applying to Stanford do you think are similar to Steve? A lot of them. Most people write what they think admissions officers want to hear in their essays and then you get some boring list of accomplishments like going to a UN conference or being the president of an honors society. Actual Stanford students write stories that make them stand out like how Dave’s passion for Japanese calligraphy developed and how it has changed his life. That is much more interesting to read than a pretentious essay full of awards and honors that you should have put in your application.

Can you share your high school experience, and how you think you appealed to Stanford? I’m a Junior in high school with quite a few B’s on my transcript from my sophomore year (it was a slap in the face). I am a section leader in my band and Vice President of Band Council, President of my environmental club and run the school garden, and President of a kindness club that I started. Getting into a top school is pretty much all I worry about(Stanford especially) and it would be really nice to hear from an actual Stanford student:)

I would have chosen Steve. In my opinion being on a sports team does not persuade me. Steve’s story however is more unique because he actually got invited to the United Nations. If I was in charge of picking students for colleges, that’s more than enough to persuade me. Also Steve worked very hard in my opinion to get in contact with those people. He proves right there that he is very persistent. I’d choose Steve.

I go to Stanford. From my experience, Dave looks a lot more like a typical Stanford student than Steve does. Steve sounds more impressive to the average person than Dave but not to an Admissions officer at Stanford

Cal, please write some blogs about more psychological hacks to use in college to become successful. “The Failed Simulation Effect” was an interesting blog. Thanks! You can also make a separate categorey for the “psychological hacks”.