In 2018, the NYU social scientist Jonathan Haidt co-authored a book titled The Coddling of the American Mind. It argued that the alarming rise in mental health issues among American adolescents was being driven, in part, by a culture of “safetyism“ that trained young people to obsess over perceived traumas and to understand life as full of dangers that need to be avoided.

At the time, the message was received as a critique of the worst excesses of the academic left and wokeism. But in the aftermath of Coddling, Haidt began to wonder if he had underestimated another possible cause for these concerning mental health trends: smartphones and social media.

In 2019, working in collaboration with the demographer Jean Twenge (who wrote the classic 2017 Atlantic cover story, “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?”), and researcher Zach Rausch, Haidt began gathering and organizing the fast-growing collection of academic studies on this issue in an annotated bibliography, stored in a public Google Document.

At the time, the standard response from elite journalists and academics about the claim that smartphones harmed kids was to say that the evidence was only correlational and that the results were mixed. (See, for example, this smarmy 2020 Times article, which amplified a small number of papers that Haidt and his collaborators later noted were almost willfully disingenuous in their research design.) But as Haidt continued to make sense of the relevant literature, he became convinced that these objections were outdated. The data were increasingly pointing toward the conclusion that these devices really were creating major negative impacts.

Haidt began writing about these ideas in The Atlantic. His 2021 piece, “The Dangerous Experiment on Teen Girls,” forcefully declared that we had transcended the shoulder-shrugging, correlation is not causation phase of the research on this topic, and we could no longer ignore its implications. The sub-head for this essay was blunt: “The preponderance of the evidence suggests that social media is causing real damage to adolescents.” (Around this time, I interviewed Haidt for a New Yorker column I wrote titled, “The Questions We’ve Stopped Asking About Teenagers and Social Media: Should They Be Using These Services At All?”)

In 2024, Haidt assembled all this information into a new book, The Anxious Generation, which became a massive bestseller, moving more than a million copies by the end of its first year, and many more since. As of the day I’m writing this, which is almost two years since the book came out, it remains in the top 20 on the Amazon Charts.

In the aftermath of The Anxious Generation, as new research continues to pour in, and we hear from more teenagers and parents about their experiences with these devices, and schools (finally) start to ban phones and discover massive benefits, it has become increasingly clear that Haidt was right all along. Last month, even the Times technology reporter Kevin Roose, a longtime skeptic of Haidt’s campaign, tweeted: “I confess I was not totally convinced that the phone bans would work, but early evidence suggests a total Jon Haidt victory.”

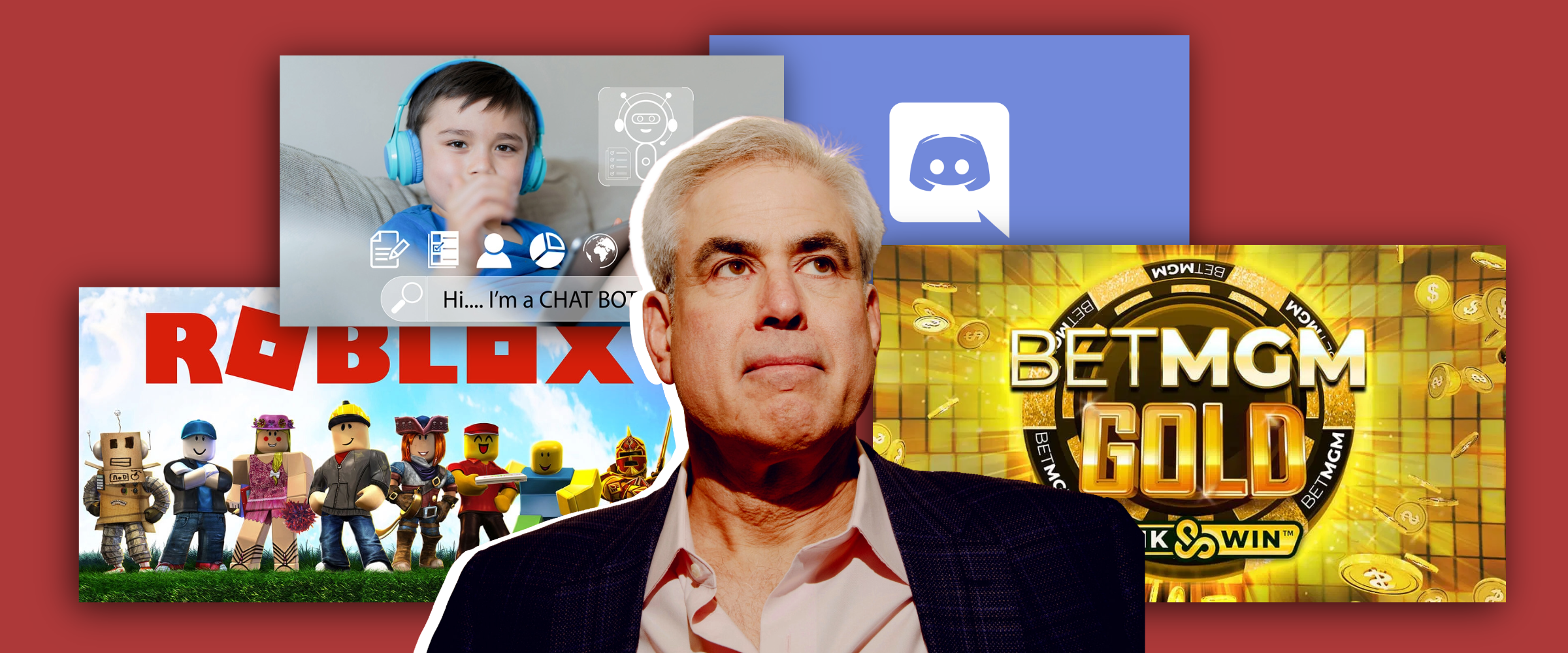

All of this history points to an urgent question for our current moment: Given that Haidt was so prescient about the harms of smartphones, what are the technologies that are worrying him now? Presumably, these looming dangers are ones we should take seriously.

To answer this question, I went back to read what Haidt and his collaborators have been writing about in the months following The Anxious Generation’s release. Here, I’d like to highlight three technology trends that seem to be causing them particular concern…

Read more