At a time when educators are increasingly concerned about technology’s impact in the classroom, the Washington Post published an op-ed with a contrarian tone. The piece, written by the journalism professor Stephen Kurczy, focuses on Green Bank, a small town in rural West Virginia, home to the world’s largest steerable radio telescope. Due to the sensitivity of this device, the entire area is a congressionally designated “radio quiet zone” in which cell service and WiFi are banned.

The thought of a disconnected life might sound refreshing, but as this op-ed argues, there’s one group for which this reality might be causing problems: the students in Green Bank’s combined elementary and middle school.

“Without WiFi, the 200 students couldn’t use Chromebooks or digital textbooks, or do research online,” Kurczy writes. “Teachers couldn’t access individualized education programs online or use Google Docs for staff meetings.”

Some teachers in the school are frustrated. “The ability to individualize learning with an iPad or a laptop – that’s basically impossible,” explained one teacher, quoted in the piece. “Without the online component of our curriculum fully working, it’s really detrimental to our instruction,” said another.

These concerns aren’t merely hypothetical. As Kurczy points out: “Green Bank consistently [posts] the lowest test scores in the county.” He quotes the school’s principal, who blames this on the students’ “lack of access to engaging technology.”

The message of this op-ed is clear. At a time when we’re rushing to condemn phones in classrooms, we should be careful not to extend this ire to other ed-tech innovations, as without these, students struggle.

It’s a tidy point. But is it true? I decided to dig a little deeper…

To start, the claim that Green Bank posts the lowest scores in the county is easily confirmed. But there’s a caveat here: Pocahontas County, which includes Green Bank, is small. It includes only one other middle school and two other elementary schools, so even modest differences in the student populations can create big changes in measured performance.

The only other middle school in the county, for example, does boast higher test scores, but it also serves only around 100 students, meaning that a small cohort of more advantaged children could explain the entire gap. (It’s perhaps notable that this higher-performing school is co-located with a hospital and across the street from a country club.)

What we really need is time-series data. The classroom iPad/Chromebook revolution took off in the 2010s, so if the lack of WiFi is what’s holding back Green Bank, we should see a unique decline in their performance starting last decade.

I couldn’t find time-series data for individual schools, but I could for individual counties in West Virginia. Given the small size of Pocahontas County and the fact that roughly half of its elementary and middle school-aged students attend the school in Green Bank, if the lack of WiFi is really negatively impacting the student population, this should be reflected in the county-level data on performances in grades 3 to 8.

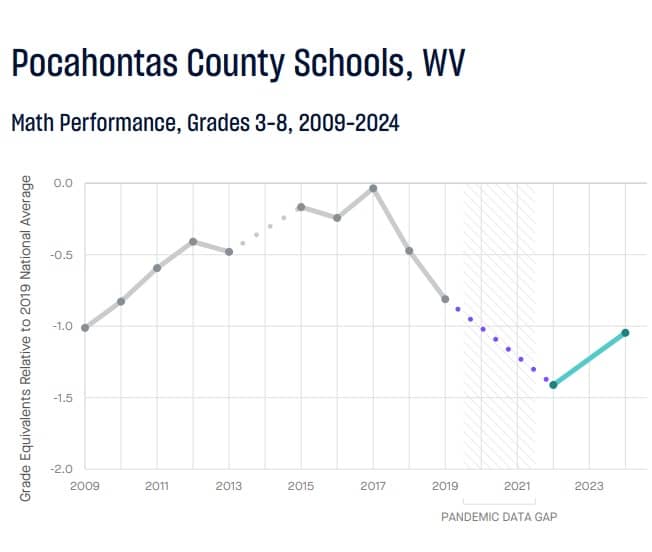

So what do these data actually teach us? First, let’s look at scores on standardized math tests in Pocahontas County over time.

These scores had been steadily increasing, but then, around 2017, they began to drop. We then see, starting in 2022, the start of a post-pandemic recovery.

The timing here seems to roughly align with the WiFi hypothesis: if iPads and Chromebooks took off last decade, then we might expect to see a negative impact on performance in Green Bank right around this point.

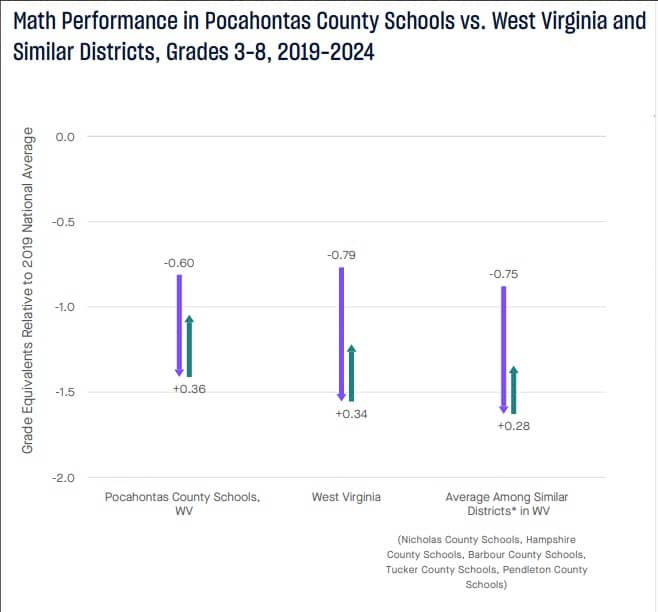

To run a proper controlled analysis, however, we need to compare these changes to similar counties in West Virginia that had full access to WiFi. Fortunately, we have these results.

The following chart measures both the magnitude of the performance drop from 2019 to 2022 and the magnitude of the subsequent recovery from 2022 to 2024. It compares Pocahontas County to the entire state, as well as to a set of five counties with similar population sizes, demographics, and socio-economic status.

The result?

Compared to other counties in the state, Pocahontas County schools had a smaller performance drop and larger recovery. Put another way: the county in which nearly half of the measured students lacked access to WiFi did better than other counties with similar student populations and full access to classroom technology.

The more plausible story told by this data is that rural West Virginia schools are struggling, and something appears to have made this worse around 2015 to 2017 (most likely deteriorating economic conditions). But the solution to these problems is likely not as simple as getting more internet-connected Chromebooks into the students’ hands.

(That being said, the fact that this school is using old technology is a problem, just for other reasons. As Kurczy’s reporting reveals – he wrote an entire book on this town – the teachers in Green Bank are frustrated. They feel left behind by the county, and they are missing out on the productivity gains we take for granted, like the use of shared documents or the ability to easily distribute assignments online.)

The big news coming out of Green Bank is that the school district has finally negotiated an agreement with the observatory to allow classroom WiFi, and, I guess, I’m happy to hear it

However, the more important reminder here – and this applies to me as much as anyone else – is that when it comes to writing about technological impacts, we have to be wary of motivated reasoning. Just because something feels like it should be true doesn’t mean that it necessarily is. The data often – frustratingly – paints a more nuanced picture.

Cal, I wonder why you (and the source of the whole argument for that matter) so readily accept the premise that digital education also must be wireless.

While the reason for the disconnect sounds sensible on the surface, it’s not like there’d not be solutions, like, you know, LAN cables.

I think the ed tech revolution relies heavily on WiFi because it’s not practical, from an infrastructure perspective, to have individual LAN cables at every desk in every classroom. It only became cost-effective when you could assign each kid their own low-cost portable computer that they could bring from room to room and connect wirelessly.

Correlation is not causation. A simple lesson that’s easy to brush aside when we emotionally desire a particular outcome. I still have to remind myself of this almost daily because of my human tendency to jump to conclusions.

There was no digital education 30 years ago, and children still did well at school. I am wondering if the teaching methods have changed for the worst in the meantime. I noticed that there is less scaffolding than before, and that the fundamentals (reading, writing, counting) are not so solid, because less hours are dedicated to them.

There are many issues to unpack in this opinion piece.

First, the core premise of education needing WiFI is easily addressed with computers connected to a wired network in every classroom. State and Federal grants exist to fund such a need. There is real need for WiFi itself. It may be easier, but that doesn’t mean it is better.

Second, the use of Google or Apple for education through their slick, hard sell tactics should be a concern. Chromebooks are a nice solution to get kids into the Google ecosystem and keep them there for life. This is the same reason Apple for education programs exist. I’ve watched local school after school get all excited about being a “Google School” and in exchange for the school district paying out millions, Google gives them bone-stock Google services at a 5% discount. There is no support, no special consideration for the needs of children, nor even training for the teachers. It is merely expected that *everyone* just loves Google.

The whole situation is pathetic. “Please save us Google/Apple from our inability to think creatively to solve the issues!” The decline of American education is real.

This gets to the core of the issue about public education. Are public schools workforce training grounds for the future workforce or are they liberal arts education in the classic sense; hopefully teaching children to learn and think critically? Before the ubiquity of the Internet in education and all these corporate programs, American children were doing fine compared to their global peers. We continue to slide down the global rankings against more advanced countries; there I said it.

The challenge isn’t lack of WiFi.

Three reasons to use WiFi in classrooms. It’s a working tool in the same way a scientific calculator is to hard science; leant to use it early. As mentioned WiFi is much simpler and cheaper than hard wired LAN. Lastly the argument about the “slick promotion” of commercial educational sites is one more way to teach people how to discriminate between advertising spin and facts.