The Remarkable Life of Erez Lieberman

Last week, a reader sent me a profile of the scientist Erez Lieberman. Now I’m obsessed.

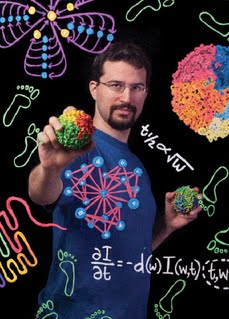

Lieberman is a Junior Fellow at Harvard’s elite Society of Fellows and a Visiting Faculty member at Google. He’s a boldly interdisciplinary mathematician who prizes interesting projects above all else. “I’m always on the lookout for new methods that I think will open up whole new domains,” he explained.

Lieberman cracked the 3D structure of human DNA, showing that our genes are packed in an esoteric geometric whimsy known as a fractal globule.

He used graph theory to improve our understanding of evolution.

He sifted through Google’s massive database of scanned books to search for statistical evidence of cultural shifts.

The six papers he lists on his web site were all published in either Science or Nature. Two were cover articles. He’s been featured on the front page of the New York Times, was a Tech Review 35 under 35, and won the $30,000 MIT-Lemelson prize for innovation.

He’s also only two years older than me.

Lieberman represents my dream of an academic career done right. He swings for the fences with wildly interesting projects which earn him recognition, but more importantly also earn him freedom. At this early point in his career, he can work on what he wants and where he wants. He’s constructed a life centered on intellectual novelty, and it’s remarkable.

The reason I’m writing this post, however, is what happened after I first encountered Lieberman’s story.

The Case Method for Defeating Procrastination

After encountering Lieberman’s profile, I dived deeper — deconstructing his CV, reading other articles on his life, and watching videos of his talks. I drew on this detailed understanding to tweak my recently unveiled research process (a process, I was happy to discover, that is already similar to how Lieberman approaches his work).

Among other things, I revamped the little bets piece to be more ambitious and boldly interdisciplinary. I also turned up the aggressiveness with which I planned to attack them.

Along with this newly improved and validated research process came a boost to my motivation to follow it. The idea that I might ignore this plan now seems inconceivable.

I’m telling you this story because it captures an axiom that applies well beyond just success in academia: one of the most effective ways to sidestep procrastination is to find the story of someone who personifies what you want to accomplish, figure out how they accomplished what they did, then base your process on their approach.

I call this the case method for defeating procrastination. It’s simple but it’s also powerful.

Of course, the fact that the case method works well makes sense in light of my recent posts on an evolutionary explanation for procrastination. These posts argued that procrastination is not a character flaw, but instead our mind rejecting a plan that it doesn’t trust (a behavior it has evolved to do).

The case method helps avoid this rejection by building this required trust. When you extract a plan from a story that generates deep aspirational longings, you’re deploying a powerful recruiting tool to get your brain — especially the long ago evolved portions that respond well to such emotion — on board with your plan. The result: no procrastination.

From Neatness to Effectiveness

The fact that the case method works well surprises me less than the fact that it’s deployed so rarely.

When we face a big goal in our lives, we’re attracted to convenient strategies — something that fits our personality and schedule, and that wraps up in a nice internally consistent logical bow. But we have no reason to believe these easy strategies will work particularly well, which makes them susceptible to evolutionary procrastination.

The case method, by contrast, is difficult and can produce strategies that are less convenient. (Lieberman’s approach to research, for example, requires an aggressive, almost obsessive attack on potentially interesting directions and expects nine out of ten such attacks to fail.) But you can also trust that the strategies it generates will probably work — making them much less susceptible to procrastination.

In other words, if there’s something in your life that’s really important that you accomplish: don’t just dive in. Start by finding someone who has already made it happen then put in the time to figure out exactly what they did right.

#####

This post is the third in my series on rethinking the causes and cures for procrastination. Previous posts:

- How to Cure Deep Procrastination

- The Procrastinating Cave Man: What Human Evolution Teaches Us About Why We Put Off Work and How to Stop

(Photo from erez.com)

Hi Cal!

I started reading your articles in this month, when i went on vacations, and they had a profound impact on my plans for this semester. Thanks a lot!

I checked out the first link of your text, and one of the things that caught my attention was the follow: “His approach stands in stark contrast to the standard scientific career: find an area of interest and become increasingly knowledgeable about it.”

How do you explain this apparent contradiction between the vision of Erez Lieberman about his work and the philosophy of “do one thing really well”?

Grettings from Brazil

Cassio Kendi

Great post cal! Love the article!

Cal, What I love about this post is not just that it describes a remarkable and inspiring scientist. Thanks for that. What is really great is that this post is itself inter-disciplinary. You draw from Lieberman’s career not just models for planning your own research and career–which might be expected–but a device to apply in a connected but in fact different and unexpected field, namely, understanding and battling procrastination. Kudos.

Cal, this is very insightful. I’ve always been interested in the lives of great people, and reading their biographies always rekindles my motivation. Biographies can be frustrating, though, because they often focus on the “what” of the person (what he/she did) and gloss over the “how”. The “how” is the really interesting part. A collection of strategies and methodologies of the great minds would be an invaluable resource…

On a related note, I was reading Einstein’s “Ideas and Opinions” and stumbled upon this gem which reinforces your education philosophy:

“It is also vital to a valuable education that independent critical thinking be developed in the young human being, a development that is greatly jeopardized by overburdening him with too much and with too varied subjects (point system). Over-burdening necessarily leads to superficiality. Teaching should be such that what is offered is perceived as a valuable gift and not as a hard duty.”

Are you kidding me? Both of your strategies here are trivial. First, your “case system” simply translates to “be more interdisciplinary” or find more opportunities for such interdisciplinarity in your “little bets” –fine, good luck with that, but how does this solve the procrastination problem? Second, starting from the lives of remarkable people and working backwards is a surefire way to develop mind paralyzing anxiety. So I look at Barack Obama, I want to be like him, I can break down every step that lead to him becoming president(or let’s say a powerful politician) –fine, I’ll follow the same steps, go to harvard law, etc. etc. But so many other factors played into his success. I want to be a famous actor. Hey I read the biography of Keanu Reeves, I’ll move to LA and start going to auditions, etc. Again, I can trace every step, I’d like to have the kind of life of either of these people –does my prefrontal cortex or whatever really believe either is going to happen for me? I don’t think so. It seems to me, that with truly remarkable people, as opposed to just getting run-of-the-mill degrees(which is what your strategies are best suited for), remarkable success really depends on a lot of factors you don’t account for.

The “don’t just dive in” approach seems better suited for grand projects like writing a book, or doing what Erez Lieberman did. I’ve found for things like improving social skills or exercising, just getting started was the biggest hurdle. Once I started then I adjusted accordingly to what was more effective. Getting started in these areas are a psychological hurdle more so than anything else.

I think it also depends on if you have developed the action habit. I’d agree that hyperactivity could have you running in circles, but doing nothing all the time also doesn’t get anywhere.

I believe it is all a matter of what your intentions are with a particular discipline or skill.

Cal, how do you reconcile his multidisciplinary approach with your philosophy of choosing one discipline and becoming so good at it that no one can ignore you?

I think Erez does do one thing really well: his particular brand of topology-centric mathematics. What he does differently than other scientists, however, is take the time to learn enough about other fields to see where he can apply this skill of his.

I find this is often the case where you find successful interdisciplinary efforts. That is, that there is a real asymmetry in expertise: someone who is world class at one thing learns enough about another to apply it (think Steven Levitt’s microeconomics work).

That’s not the case method. That was the result of me applying the method to this specific case study and a specific research goal of mine.

The case method itself is broader: use people whose stories generate aspirational longing as the foundation for your practical systems.

You’re asking whether this approach to reducing procrastination will guarantee to make you president?

You seem to be reading my post as: “here is a system to accomplish any goal or get any job.” That’s puzzling to me.

I’m trying to provide practical methods for people struggling with practical goals. Let me re-summarize: If you’re worried about procrastinating in an important pursuit in your life, don’t dive right in, instead work backwards from the story of someone who accomplished it before you. This will produce tactics that are more resistant to procrastination.

The case method can help greatly reduce this psychological hurdle. If you encounter someone who is fit and enjoying life, and you find out that they have some specific approach, this can really lower your barrier to entry.

Thanks for switching back to the old design. I admire your efforts to try and improve the site. I’m not opposed to change, and if you find the time, feel free to try a new design. However, this one is usable, cute, and distinct–though, perhaps, not as trendy a layout as Zen Habits.

That reminds me of something that has been bothering me for quite sometime. Why is “the East” (e.g., “Zen,” “Yoga,” “Meditation,” etc.) trendy?

(In the village my family lives, people simply go to the top of a local mountain at sunrise, meditate, stretch as best they can, and go on with their days. They don’t carry around rubber mats, go as a group, listen to chants on a CD player, and talk of their “newfound feeling of peace.” Yoga is something people can do without sensationalizing it by saying, “I feel more at one,” and whatnot.)

Whenever I see “Eastern” traditions being advertised on the East Coast, I’m usually reminded of apple marketing its latest gismo. I guess I should be flattered.

Cal,

You write, “I think Erez does do one thing really well: his particular brand of topology-centric mathematics. What he does differently than other scientists, however, is take the time to learn enough about other fields to see where he can apply this skill of his.”

This clicks for me. The work that wins MacArthur Fellowships, the so-called genius grants, is often interdisciplinary. Here’s last year’s list. https://www.macfound.org/site/c.lkLXJ8MQKrH/b.6239745/k.FB13/2010_MacArthur_Fellows_Announced.htm

Closer to the scientist’s original training, an entomologist once told me that no one had ever studied a new species without making a contribution to the entire field.

My theory: A return to simplicity is trendy (reaction to latest ramp up of consumerism) and some eastern traditions provide a nice metaphor for that thinking.

Yep. There seems to be a trend in here. Master something hard and useful. Then learn just enough about other fields to apply it.

You could read about the influence of role models.

Superstars and Me: Predicting the Impact of Role Models on the Self

Hey Cal, I know this doesn’t completely pertain to this blog post, but I have had a question on my mind.

I really would like to employ the principles you talk about, but I feel like my stress is not necessarily coming from academia, but rather my family life. I would like to be successful and get into a good college, but there is so much stress from my family and so many things that are limiting what I can do. I feel like I am a flower that doesn’t have the right soil, amount of water, and amount of sunlight to flourish. I could do so much more were it not for my family situation, but college admissions seem unfair, as all people come from a different home life of varying stability. In my case, the excessive instability is disallowing me to be as exceptional as I can be and want to be. I don’t know if you have any advice for me, but I sure as heck could use some advice. It seems like I get emotionally upset now and then because of my family’s situation that I am not procrastinating, but rather am doing what I must do – maintaining emotional homeostasis, if you will. By doing that, I feel like I’m not able to focus on the task that needs to be done, and I just need some advice. You’re a role model to me, Cal. I couldn’t find your email, so if you need mine, it’s [email protected]

Thanks Cal.

Hi Cal – I read your blog all the time and love it! This is the first time I am commenting though, but I just can’t help myself this time. I have to repeat what someone else wrote in one of the earlier comments: Are you kidding me??? Seriously!

Honestly, I normally think that almost everything you have to say is great, but I have to say that this post of yours has me totally confused. I was utterly certain when I started reading your blog post–after reading the fluff piece in the online magazine that you linked to–that you were going to go on to turn this guy Lieberman into a cautionary tale, rather than holding him up as your perfect role model. You say he does “wildly interesting projects which earn him recognition”: surely we couldn’t have been reading the same profile of the same guy! Yes, of course it is extremely impressive to have all those Nature and Science articles but please bear in mind that they are mostly really really short and do not represent anything like a series of important scientific advances. Their evolution/social networks paper in Nature is extremely brief, setting out a theoretical framework but with no empirical application, so how can we say if it is useful or not in understanding something important about actually existing social reality? They throw in a sop to empirical reality in a couple of throwaway lines at the end of the article, mentioning only two possible (wildly diverging) empirical applications of their entirely theoretical study. Their empirical hypothesis for their proposed study of “certain animal species”–not even naming a single possible species that might be appropriate–is frustratingly (and laughably) vague, and then they conclude with an off-the-cuff utterly meaningless ‘prediction’ about human social networks: that “[t]he fewer friends I have the more strongly my fate is bound to theirs.” How in the world can such a vague and vacuous sentence shed any light on human behavior in empirical reality? The Science paper using the Google books database yields “wildly interesting” research findings such as “two central factors that contribute to culturomic trends”: (1) “[c]ultural change guides the concepts we discuss (such as ‘slavery’)” and (2) “[l]inguistic change–which, of course, has cultural roots–affects the words we use for those concepts (‘the Great War’ vs. ‘World War I’).” To translate into plain English those utterly vacuous statements that they have tried to present as serious scholarly insights, we get: (1) people discuss topical things (2) when referring to famous historical events, people don’t use phrases that haven’t been coined yet. To empirically back up these bold assertions, the authors used the awesome power of a massive dataset of millions of books digitized by Google to show that people were more likely to use the word “slavery” during the U.S. Civil War than other time periods, and that people didn’t use the phrase “World War I” before “World War II” began. Presumably, until Lieberman’s “wildly interesting project” came along, historians thought that people used the phrase “World War I” even when there was no “World War II” that had to be distinguished from it.

Come on, Cal – it’s clear that Lieberman violates almost every single one of the tenets you have been drilling into us all for years. Like several other commentators have written, Lieberman represents almost the exact opposite of your crucial argument: don’t ‘follow your passion,’ but rather pick one thing to get really really good at, though sustained training to achieve hard focus, with the ultimate aim of being so good (at your one, highly developed, but also very rare and valued, skill) that “they can’t ignore you.” This guy doesn’t fit with that at all. Now, of course I don’t want to make out as though this Harvard Society of Fellows Junior Scholar is not a really smart guy who has had great success in his career, but I honestly fail to see what is so fantastic about him that he should serve as your role model. First, the linked article is just a fluff piece on an academic whose career makes for an interesting short article that’s somewhat entertaining. There’s nothing in that article that makes me think this guy is an exemplar to follow as an academic. He’s quirky, for sure, and his discovery of “the three-dimensional structure of the human genome” is obviously a really important discovery. But the article doesn’t give the crucial detail we require about the way in which he make his discovery that would allow us to assess his relative “genius” versus his extremely fortuitous stumbling upon an old, long-forgotten journal article. We have to know more about how he came across that old article in order to know if it was more a case of good fortune or something specific about his way of working that kind of ‘inevitably’ meant he alone could make that kind of discovery.

His research project which uncovered a mathematical formula to predict how quickly irregular verbs will “regularize” over time superficially ‘kind of neat.’ But is it actually *important* (either substantively or theoretically)? What thing of great importance did that research give us? Who actually cares about a solely *empirical* finding that the speed at which some verbs “regularize” hews to a mathematical formula, but we have no idea why that should be, or whether it tells us anything important at all about language? Does it matter in any meaningful sense whether more people say “learned” than “learnt” right now? I think you’d be hard-pressed to find someone who would say this is a really significant piece of scholarship. A small band of scholars, of course, would think this really important, but there’s no way that’s a significant “interdisciplinary” piece of research. Most importantly, he has empirically uncovered a mathematical rule, but told us absolutely zero about the theoretical importance of that empirical finding, if there is one at all. What plausible mechanism could we think of that would account for this empirical finding? If we can’t think of one, then the empirical finding on its own is just a neat little curiosity: we say, ‘huh, that’s kind of interesting,’ and then forget about it just as soon as we read it.

And is it a good model for a satisfying and intellectually stimulating career as a scholar to have an approach to selecting research projects that seems to just be going to whatever talks are on at your university, being struck by some factoid or other, and then just abandoning any previous body of work you had been building up previously to go chasing something totally new? That doesn’t sound like “be so good they can’t ignore you”: who exactly are going to be the “they” who “can’t ignore” him once his Harvard postdoc ends? If he just has a string of journal articles that are all over the place substantively, and he is just dipping in and out of all sorts of disciplines, what specific discipline’s faculty at *any* university would rather give him a tenure-track job over an actual specialist in their own discipline, who has shown an actual commitment to their discipline and not shown a career track record that suggests he’d drop that discipline in a second just as soon as some other mildly interesting factoid from some unrelated discipline slips into view?

It seems more like, as you said, he has an empirical method (“his particular brand of topology-centric mathematics”) and he just sort of casts around for whatever empirical context he could get away will applying it to, and then just seeing what happens. Is that a good example that we should build our academic careers on? You imply that he is an eclectic interdisciplinary scholar who shuffles from discipline to discipline, sticking around just long enough to shake it up by making an important discovery. But I have a really hard time believing that specialists in the fields he drops in and out of would see his research as a serious contribution to their disciplines (except presumably the people studying the human genome).

Finally, “culturomics” is surely his least meaningful pet project. Playing around online with the Google N-grams viewer is without doubt a fun and really addictive way to pass a few mindless hours throwing words into the search box and seeing what pretty graph is thrown up. But it is emphatically nothing more than a mere idle distraction from the kind of “hard focus” work that you emphasize we need to do to build a satisfying career. What really meaningful and important substantive and theoretical inferences can you draw from using the N-Gram viewer? It’s just another piece of fluff pretending to be a groundbreaking advance that will shake up loads of disciplines.

The things you can use the N-Gram viewer to check out are hardly riveting. Most obviously, when you search some terms and it spits out some graphs, it is almost impossible to use the graphs to draw any inferences about anything meaningful! I’m not saying it’s not a wonderful project by Google to attempt to digitize by 2020 all the books there have ever been, and to make them fully searchable with N-Grams. That’s pretty cool. But in all seriousness, Cal, I challenge you to come up with a genuinely important and interesting research question (preferably some knotty, long-standing, open question in some discipline that has stumped that discipline’s great minds for a long time) for which the N-Grams viewer is uniquely placed to provide an unambiguous and important answer. (Or, indeed, let’s not even require it to be “uniquely placed” to give a solid answer to an important research question: just any genuinely important research question that N-Grams viewer can give a reasonably clear answer to that isn’t already obvious to any sensible person and/or couldn’t already be straightforwardly answered without resorting to a gimmicky ‘method’ like N-Grams.)

In the Science article outlining this empirical tool, they just give a bunch of unconnected demonstrations of some questions that you might use N-Grams to investigate, but their findings from the N-Grams tool are hardly exciting, let alone groundbreaking and let alone being of reasonable interdisciplinary interest. They used N-Grams viewer to show that China censored the use of “Tiananmen Square”–what an amazing finding! And that the Nazis kept Jewish artists and academics out of German books during Nazi rule. Seriously, Cal, who would possibly have seriously argued for rival theories that China didn’t censor “Tiananmen Square” after 1989 and the Nazis didn’t censor Jewish authors. If your data is just confirming what everyone on the planet already knows and absolutely no-one would dispute, what is so admirable about this project? Similarly, the examples of N-Gram searches used for the New York Times article on “culturomics” are not exciting at all: the use of the word “women” sharply rises upon entering the 1970s, as the use of the word “men” starts to drop around the same time. What possible explanation could there be for this fascinating empirical result? The comparison of the use of the words “fry” and “grill” from the 1950s to the 2000s is kind of neat, until we ask what possible important research question might a scholar want to pose that this graph would really help in answering. Finally, there is a graph showing that Jimmy Carter was mentioned with much greater frequency than Marilyn Monroe from around the time he became President. Does the finding that Jimmy Carter was a lot more likely to be mentioned than Marilyn Monroe while he was the President of the United States genuinely surprise anyone? And the example given of the kind of projects that “vindicate the project’s value” is someone putting up a series of graphs revealing–to everyone’s amazement, I’m sure–that people mentioned phrases relating to the atom a lot more in the 20th century than the previous one. And, in an amazing counter-intuitive twist, we discover that people didn’t mention Chernobyl much in books until around the time of the disaster. And then mention of Chernobyl became less frequent again as time wore on.

So, Cal, honestly, what’s the appeal of a guy who jumps around from substantive area to substantive area making a series of superficially interesting empirical findings but which on second thought lack any kind of serious theoretical depth or sophistication. He just seems like a charming chancer who jumps at any research opportunity that presents itself, without thinking deeply and carefully about he will build a research career that hangs together, and without building up a satisfyingly deep and rich body of cumulative scientific knowledge about a relatively specific research area that might allow him one day to “be so good they can’t ignore” him. I really do think he represents almost the polar opposite of everything you have been trying to teach us for years!

Point taken, of course my e.g. of the president was extreme, but didn’t your advice instruct to suggest remarkable people. It seems to me that selecting remarkable people is precisely the way to decrease your belief that you can similarly accomplish such a thing. Also doesn’t someone like this undermine all the so called 10 000 hours of practice, be good at one thing, etc. etc. advice out there –doesn’t she exemplify the value of courage and passion more than your examples of wannabe rappers, screenwriters etc.? And she seems to have accomplished it all in a relatively short time and moreover, by carving her own individual path, not reverse engineering from someone else’s example.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/brit-marling-of-another-earth-does-stardom-her-way/2011/07/19/gIQAhmijTI_story.html

@Declan: “And she seems to have accomplished it all in a relatively short time.”

Given the title of that piece includes “does stardom her way,” it’s not surprising she’s portrayed as an overnight sensation.

A less fluffy article paints a more realistic picture – https://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2011/07/18/brit-marling-another-earth-her-journey-from-georgetown-to-sundance.html

“It’s courageous to take charge of an artistic career, but Marling has been doing that since she was a little girl. The daughter of real-estate developers who moved a lot, following projects, said her nomadic lifestyle as a child influenced her choices as an adult. Back then, theater was her only constant, and she grounded herself by writing and directing her own plays and casting her friends.”

“after graduating from a performance arts high school in Florida.”

“she and Cahill moved to Cuba for a year to film a documentary”

“The trio lived together in a house in Silver Lake, where they did nothing but write, read textbooks about screenwriting, and analyze films.”

“Marling would spend half a day with Cahill writing Another Earth, which he directed, and the rest of the day writing with Batmanglij, who directed Sound of My Voice.”

And in response to “not reverse engineering from someone else’s example” –

“As the engaging and self-possessed Marling stands at the threshold of stardom, she is pondering which version of herself—writer or actor—might figure more prominently in her future. She appeared in one episode of NBC’s Community last season and recently completed filming on her first big-budget movie, Arbitrage, with Richard Gere.

For the answer, she said, she looks to the Tina Feys and Kristen Wiigs of the world.“

The find-someone-to-emulate approach does not seem likely to work for me. You need to find an approach that works with your way of thinking, and the person you choose to emulate may have had a very different thinking style. Some people succeed by being very narrowly focused, others by having a breadth of knowledge and interests. Some people pick up projects and work on them intensely in short bursts, others work at a more measured pace but stick with the same project longer. Trying to match someone else’s optimal working style is likely to lead to frustration if it is not a match for your own optimal style, ending up with more procrsatination, not less.

Of course, your approach also assumes that you find other people’s success inspiring. Some people do, but I don’t. I find biographies and autobiographies (even of people whose work I admire) to be extremely tedious. About the only time I’d consider your approach would be if I needed to go to sleep quickly and needed something very boring to read to put me to sleep.

Didn’t someone already provide you the link as a comment on the “Double majors don’t publish novels” post? You refused to publish it! Anyways, happy to see you’ve answered the question of interdisciplinary vs specialist.

Interesting assessment…

I didn’t read his work as closely as you did, but I came away with the impression that he’s on track for a fantastic career. (Keeping in mind that I just came off job hunting myself, so I’m still in that hiring committee mindset.)

One approach that comes to mind: get into the best college you can right now. Once there, you will encounter the stability you were missing before. This is the time, perhaps, to hit the ground running and starting taking your potential out for a spin.

To prepare for this impending opportunity, now is a good time to start getting your mindset, strategies, etc., in order and practiced.

As Tyler nicely illustrated in his reply to your comment, I find that digging deep into remarkable people’s lives is motivating, as you get past the myth of genius and find the underlying patterns of success. These are sometimes difficult, ambitious patterns, but at least they’re clear.

I think the case method works best when you feel a sense of connection to the details of the story, which might in turn require a matching of approaches.

That being said, I’m not a big booster of the “different styles of working/learning” etc. camps — some things are more universal than we might expect.

Comments from first time commenters are held in moderation until I approve them. I approve everything that’s not spam. I also have an autospam filter, however, that sometimes throws out non-spam.

Hello Cal,

Thanks for this article about Erez Lieberman. Before college, I was part of another lab competing with his group to crack the 3-D structure of the DNA. We published our findings on Nature a couple of months after Erez Lieberman’s published theirs in Science. The professors I worked with seemed to have deep respect for for his youth and intellect. I was determined to emulate him and have continued with research in college. I completely agree with your suggestion that an effective way to be inspired is to find the story of someone who personifies what you want to accomplish. Thanks for reminding me. 🙂

D ’14

@Tyler –thanks for the article. Jesus, AND she was a successful economics major good enough to be offered a job by Goldman Sachs. It is interesting though, both Brit Marling and Erez seem to have a lot of collaborators on all their projects.

I should say, I do agree with some of Tom’s comments as well about Erez –even though watching his TED talk clearly demonstrated he has a quick wit. For example, on his website he has various “art projects” –they are absolutely pathetic and no self-respecting artist or art historian would give them more than a moment’s attention. In a sense he HAS done one thing fairly well but has coupled it with extravagant self-promotion and self-mythologizing. Most of his “spin-off” projects though are fairly trivial. Nothing wrong with that –as Ted Turner used to say, “early to bed, early to rise, work like hell and advertise.”

What to do when your role model “DOVE IN” and happened to be lucky?

Lucky for me, my role model did not and I figured out what she did, but for many others… that is not the case.

Julie and Julia, the movie based around Julia Child’s cooking and recipes, seems to fit this. I don’t know maybe Julie procrastinated coooking dinner everynight, and this project took her to a completely different level and inspired her out of complacency.

Personally, I do agree with your stand that “procrastination is not a character flaw, but instead our mind rejecting a plan that it doesn’t trust.”

I have had a really hard time trying to fight against procrastination. I have been believing that “motivation”, “determination”, “planning”, and “complacency” are the four main causes. However, there is still something missing, and now I know what it is 🙂 thanks

one of the most effective ways to sidestep procrastination is to find the story of someone who personifies what you want to accomplish, figure out how they accomplished what they did, then base your process on their approach.

This is exactly what motivational speaker Tony Robbins has been preaching for years. Seems to have worked well for him and his clients.

I do think this guy has a niche. I was reading an article about Ben Mezrich, the guy who wrote about the MIT blackjack club, who published another book about the interns who stole moon rocks from NASA. Apparently the moon rocks people contacted him – he’s now known as the guy who writes up crazy true stories about geeky mischief. Now, I have the literary talent of a tortilla chip, but I still think that’s a pretty awesome life. If he can do that, then there’s nothing wrong with being “the guy who does crazy applied math”.

He’s also a very good writer.

This may be the key of his strategy. Say you are a mathematician, it takes a lot to out-rank great mathematicians. But if you go next door to biology, you are better at solving some problems than the best biologists.

There’s a folklore:

“Tian Ji was invited to participate in a horse-racing event hosted by the king and Sun Bin proposed a strategy for Tian Ji to win. Tian used his inferior horse to race with the king’s best horse, his average horse to race with the king’s inferior horse, and his best horse to race with the king’s average horse, winning two out of three races.”