Deep Tracking

I’m obsessed with deep work. I believe it’s the key to crafting a meaningful and interesting career. And yet, even I — Dr. Deep Work himself — sometimes struggle to fit enough of it into my weekly schedule.

I recently set out to find out why…

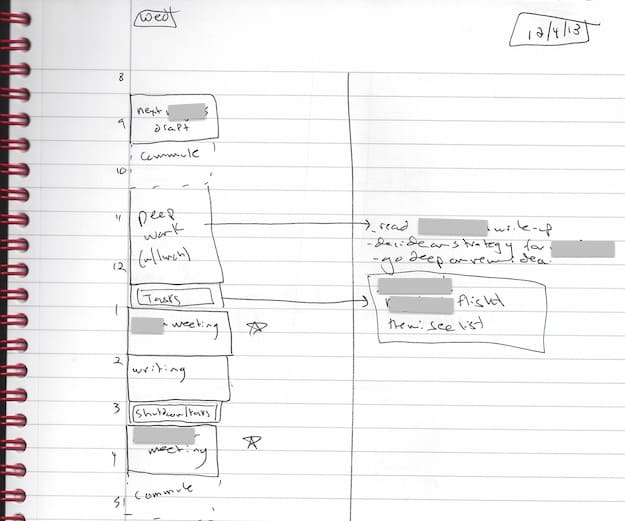

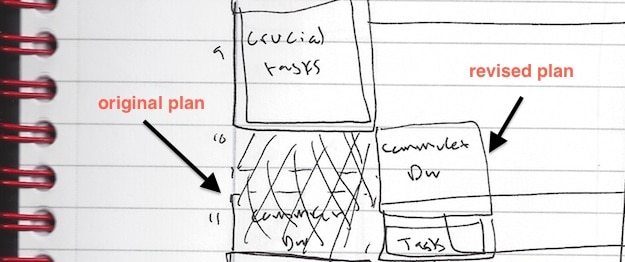

Fortunately, I have a good data set to use in this effort. As readers of STRAIGHT-A know, I believe in time blocking (if you don’t plan every minute of your day in advance, your efficiency will plummet).

I use Black n’ Red notebooks for this purpose, one page per day. As shown in the above picture, I hold on to my old notebooks so I can study my habits when needed.

I went back through the notebook I used during my fall semester and identified two weeks: one which was good (close to half my time was dedicated to deep work on research and writing), and one which was bad (less than a quarter of my time was dedicated to these efforts).

My goal was to understand the difference between these two weeks, and by doing so, hopefully identifying the scheduling traps most damaging to efforts toward depth.

(I recognize that even my bad week represents more deep work than most are able to fit into their schedule [I’ve been at this for a while], but what matters here is the relative difference in time, not the absolute values.)

Read more