Tangent Troubles

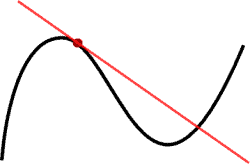

Calculus is easy. Or at least, it can be. The key is how you digest the material. Here’s an example: when you’re first taught derivatives in calculus class, do you remember it like this…

![]()

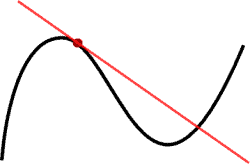

Or do you intuit this image…

As I will argue in this post, for any technical course — be it calculus, physics, or microeconomics — the key between an ‘A’ and a struggle comes down to this distinction. Below I’ll explain exactly what I mean and reveal how top technical students use this realization to consistently ace their classes.

How Every Technical Class is Taught

Technical classes have a simple structure. In each lecture, the professor presents a series of concepts. Depending on the difficulty of the material, she may cover anywhere from one to more than a dozen. For each concept, the professor will derive the result from concepts you already know and/or provide an example of the concept in practice.

That’s it.

This simplicity is good. It will make it easier for us to develop a strategy to conquer the material…

The Magic of Insight

What do you do with the concepts being spewed by the professor? Most students dutifully copy them down along with their accompanying examples. For example, if it’s the first week of calculus, you might record the standard derivative equation I reproduced above.

This is fine, but it’s not enough….

In addition to capture, you need to develop insight.

What do I mean by insight? That click in your brain — the moment when the tumblers of your mental locks align, the door swings opens, and an intuitive sense of what and why come flooding out. Forget the equations you copied from the blackboard, I’m talking about developing an understanding deep down in your bones.

For our example of the derivative, this might mean having a solid mental grasp of this image:

A derivative at a given point is just the slope of the tangent line that kisses that point. Even more intuitively: it can be though of as the “steepness” of the graph at that point. That’s all. The complicated equation from above is just a way to calculate a specific number that describes this steepness.

If you understand this graph — really understand it — you understand the insight behind derivatives. If all you know is the equation from above, then you’re screwed.

Insightful Studying

I am now ready to reveal the big dark secret about technical class studying: If you want to do well in a technical class all you have to do is develop insight for every single concept covered in lecture.

That’s the whole ballgame.

That’s how every high-scoring technical student does it.

There’s no shortcut.

It’s the only way.

Here’s what I commonly observe: the students who struggle in technical courses are those who skip the insight-developing phase. They capture concepts in their notes and they study by reproducing their notes. Then, when they sit down for the exam and are faced with problems that apply the ideas in novel ways, they have no idea what to do. They panic. They do poorly. They proclaim that they are “not math people.” They switch to a philosophy major.

Without insight you can’t do well.

How to Develop Insight

Developing insight can be hard. (Though it gets easier with practice.) Especially when you’re given a dozen new concepts per lecture. The implication: you have to invest a lot of effort during the semester — not just right before the exam — to keep up with a technical course. Every one of those concepts described in lecture has to be translated from symbols on a blackboard to a shiver-inducing deep comprehension. It’s not easy, but at least the challenge is now well-defined.

Here are some tips that can help:

- If you have a hard time understanding the material as the professor presents it, prep the concepts before class by reading the textbook.

- Ask questions when the professor loses you. Often their answer can knock you back on track to insightful understanding.

- Ask the professor or TA for clarifications immediately following lecture.

- Try to review your notes as soon as possible after class to cement insights while the information is still fresh in your brain.

- Always go to office hours. But before you show up, spend time with the troublesome concepts trying to build insight. Figure out exactly where you get stuck. This will help the TA or professor give you targeted, useful advice. Never just say: I don’t get it.”

- Keep a running list of every concept taught so far in the semester. Mark the ones that you have an insight for and the ones you don’t understand. It helps to see clearly exactly what insights you still need.

The Practice Factor

Once you’ve developed an insight for every concept in a technical course, the final step before a test is to do a small number of practice problems for each to practice applying it. (This is where the mega-problem sets of Straight-A come into play.)

Here’s the crucial observation: if you skip the insight-generating phase, no amount of practice problems will help you side-step exam disaster. If it’s a week before the exam, and you lack insights on most of the concepts: you’re out of luck.

It’s Not Easy, But It’s Also Not Complicated

It’s hard to do well in technical courses. But it’s not complicated.

During the semester, you have to see yourself like a lone soldier trying to fight back the tide of encroaching concepts. Do everything you can to build insights in the heat of battle. Become obsessive about conquering concepts.

Once you’ve turned your attention to the real battle needed to do well in technical classes, you can invest your time and energy exactly where it’s needed.

And if not, there’s always philosophy…

Cal,

This post couldn’t have come at a better time! Thank you!

You’re absolutely spot on: insight is the key. Kalid Azad (https://betterexplained.com/) calls it the “a ha” moment. His website has several articles you might find useful.

What exactly qualifies as a technical course? I find myself doing this for my hydrology and biology classes, but they involve more complex systems and memorization than math concepts.

Roughly speaking, courses with math or similar logic-based problems (i.e., theoretical computer science.)

Roughly speaking, courses with math or similar logic-based problems (i.e., theoretical computer science.)

or perhaps formal logic? you know, the study of logic? but that’s philosophy, so it can’t be technical..

Then would you recommend using a computer to take notes, or would you recommend pencil & paper? I currently take notes in my hydrology class (good combo of equations & bulleted concepts) with Word and the Equation Editor, but would this be applicable for a Calculus course?

Wow, I shudder to think what kind of response you’ll get from philosophy majors!

What you said captures everything I ever learned (the hard way) about the optimal way to learn. I definitely know the awesome feeling when my mental gears click into place. I experienced it a lot while learning physics. Every new concept simply falls into place, as if it couldn’t help being there given the other concepts I’d learned. It’s an addictive feeling!

I would argue though, that the rate at which many science classes move makes it very hard to stop and turn things over in your head until you can achieve deep comprehension. I took Stats last year and the class moved very quickly to a point where it required vastly more math knowledge than the class had to justify why stat tests are done the way they are done (so our prof was always like, “If you want to know that, take Probability.” Good call.)

I’m all for learning a moderate amount very well rather than learning an encyclopedia’s worth superficially, but some course objectives necessitate the latter. It was very frustrating not understanding things thoroughly. Next semester I’ll have to take a biopsyc class whose teacher lectures so fast, it’s all people can do to put things down, then go home and digest it all. The thought doesn’t make me happy. Did you ever take a class like that and what did you do?

@Amy: I think that’s the kind of question you’ll do better to figure out for yourself rather than have someone tell you. Just try taking notes with a computer and a pencil and see what works better given your notetaking speed and the materials.

I’ve always found that taking written notes is better for me. If I’m typing then I’m not really thinking about what I’m getting down. So while I have them for later, I’m not really thinking about what I’m doing. When I write then I’m at least having to pay attention and can hopefully jot down questions that might come up or concepts that help me.

I find a good set of notes is amazing to have, particularly for review, but as the writer expresses, if it’s all you’ve got, you’re screwed when you go to write an exam.

this is a great post! it’s exactly what I’ve learned the past 3 years of engineering classes. There’s no quick and easy way to gain insight – it’s a gradual process that can’t wait until the week before a major test…

Definitely a helpful post. I feel like the quiz and recall method tests ‘insight’ particularly well, since you have to explain concepts back to yourself outloud, in your own words.

@Linh, cmon!

you know there is no discrimination or anything against any other major, just an example in which you do not need calculus to graduate.

I think this post hits home. Speaking of which I did send an e-mail about how to study for Calculus(but i didn’t respond, sorry!)I’ve never done the insight step, but I have followed the tips. I guess I should follow this article when I retake Calculus.

Lay off the philosophy majors already – philosophy is tough in its own way.

I would argue that this post also reflects what you need to do well in music performance classes. There is just a different application. To play a phrase a certain way, you have a formula that tells you when to play each note, etc. To actually play it well you have to not only understand the formula but know what’s going on behind it and how to do that with your instrument. You can’t fake it, and you can’t just learn how to read music. You have to learn how to play it.

As a right brained person, I’ve always found that the technical courses were the death of me. Being a visual learner, I have to have an image to represent a concept. So I’d have to agree with this post being very useful and probably the key to most courses out there. That being said, some of the best technical courses I’ve taken, the instructor has done an amazing job taking abstract topics and making them concrete.

Posts like these make me glad that I placed out of Calculus I and II, although at times I consider what it would be like as a mechanical engineer over a biology undergrad.

Great post! More of these technical posts will be greatly greatly appreciated!!!

To fulfill Linh’s expectations (probably not):

I major in philosophy and actually, these tips come in quite handy.

But to switch so a philosophy major if you tend to skip the insight-developing phase is not the best idea I read from you.

Currently, I’m thinking of my philosophy class as a technical course, because the vocabulary being used is technical. I wonder how well this approach would work for that [bi-weekly hell]?

I studied a lot of philosophy both at college and grad school. It was harder than any math course I’ve ever taken. I like to imagine that when new philosophy students complain about the difficulty, the professors say: “if you can’t hack it, go become a math major.” There’s a nice symmetry to that…

I find that it is a great post to keep up the motivation in taking calculation subjects like math, micro and econometrics.but to undermine that the reading and theory subject also not fair.every major has its own strong point.so don’t look down on other majors.

In How to Become a Straight-A Student I recommended using pencil and paper for technical courses. That’s my approach. But then again, I’ve met a lot of people with those fancy Tablet PCs where they can take notes on the screen, which seems to work as well…

Exactly! That’s why in my last book I talked about adding “technical explanation questions” to your mega problem sets — to make sure you’ve got the key insights down.

Very interesting…

I’m trying to keep at least one technical post per week…

Tell us more about the specific study challenge here…

What a great post, it’s exactly what i have to do with subjects like microeconomics, macroeconomics and others. It is really amazing how you capture the intuition thing, wich is fundamental. You should write more about this stuff, it’s very interesting and there’s a lot of us out there studying to become an engineer, so would be very helpful.

P.S (Sorry about my english)(Greetings from South America, Chile)

Excelent post Cal. I will start applying these techniques in my finance and accounting courses.

I find this easier said than done.

Unfortunately, it only requires more studying if this technique doesn’t help you. Also, your school may not have a good teaching core for the computational sciences. I consider myself smarter than most and if I don’t study…then I will fail every class I step too. It’s not about scan-trons or looking at your friends test anymore to see the right number to put down; collegiate math will show you how committed you are to school. I would say that .625% of the world is of a savant nature and could sit into a math class for two weeks and completely ace everything on the test without having to take notes or complete any homework. In addition, about 60% are hindered by a congenital illness (ausbehgers, autism). Think of homework as fun; think of your quizzes as check marks for your progress. Every math class will drop the worst test, a C is not bad, and every university will have a department curve unless your at MIT, Carnegie, etc. Do not fear math but only fear the laziness which dwells in us all.

@a,

practice with something relatively simple, then go more complex as you feel comfortable.

Agreed.

However it is so refreshing to see a post that isn’t catering to liberal arts majors for once 🙂

Please don’t insult other fields. I am a statistics major, which is very hard. Sure, to me that seems more challenging than philosophy or liberal arts.. But that’s because I am not those majors. They are harder in much different ways! Even if what I am doing is much harder… who cares? Everyone is just trying to get by. Focus on yourself and how you can improve, don’t focus on how you’re so much better than other people. That makes you bitter and unimpressive.

Great article, thanks a lot. =)

What would you say to someone who believe they DO understand the concepts, but maybe doesn’t because they still do poorly on the exams?

I find that this is my problem in my math and physics classes. I can usually follow what the professor is saying in class, I can see how he does the example problems. I can even do the hardest HW problems from the book and beyond (albeit I do these in the comfort of my apartment and not in a lecture hall, and sometimes they take me awhile, but I DO eventually figure them out), but then when the exam comes its like I’ve never seen those types of problems before, those “problems that apply the ideas in novel ways” as you said.

I am hesitant to go to office hours because I never have “specific questions” which is what the TA’s and professors usually field. It’s so frustrating to always go into the exam confident, but always leaving angry and disappointed.

Any advice?

@Golden Bear

I’d take along the lecture notes/problems you’re working on to office hours. As Cal pointed out in an earlier point, showing the professor your partial solution to the problem will tell that professor exactly where you are stuck and what conceptual difficulties you are having. It will also set you apart from all the other students who come to office hours looking for the solution.

OMG!! THANKYOU CAL! I’ve been looking for these type of articles for long. Looking forward to more of these. Question though, assuming this applies to high school as well as I am a high school student. I am often one of those people who say I’m just ‘not a maths person’. Teachers always tell us its effort and hard work and that if you work hard and do the work you’ll get the results. I’ve worked hard the entire year and still really struggle in technical subjects like maths. I can do all the problems from the textbook in class, even my teacher says I should get A the entire year but I never do, even with all the revision I do. It really sucks, I walk out of the exam and figure out what I did wrong. There are a few straight A students in my grade and after reading this, I have no doubt that they use insight, probably without knowing it. But do you honestly believe that everyone can do it? I think intelligence plays a big part which doesn’t give me hope. I hate that I’m surrounded by genius friends who are in a far different league than me but with common goals.Their constant ‘i don’t study’ line is really annoying and they always get an A. It’s also interesting that the people who have a mathematical brain don’t do very well in humanities and vice versa. They would say ‘I could never do history’…

I also agree on both points. But having faced those novel problems in calculus and having done very well in calculus, I can wholeheartedly say that this was the key to my success. More please. After all, Cal, you’ve conquered these technical courses. what you did and what worked for you. I’m also going to be thinking about this issue some more.

Sorry, I meant to say: “tell us what you did and what worked for you.”

What seems to work is the combination of insight building plus practice of deploying the insights (i.e., through practice problems in your mega-problem sets.) If you have insights without application practice you will freeze up — as you’ve experienced — on the test when you have to apply it.

At the high school level? Of course. The difference between students is simply their confidence and exposure to the material up to that point. The student’s who have always been told they are math people, tend to attack problems with more confidence, and struggle longer until they get answers — a type of delibrative practice that increases their ability.

You can catch-up. It does take time, but the right type of time. Make sure you have the insights learned. Then practice doing novel problems under time pressure. Work on your test-taking tactics. You’ll catch up.

Heh.

No offense taken re: the philosophy cracks. However, I’m not sure how useful the advice to switch to philosophy is for those unable to develop mathematical insights, considering high-level mathematical logic is often, if not a required course at the undergraduate level, at least required for success in upper-division philosophy of science courses, etc., as well as being a robust field of philosophy in its own right. This is true of every major analytic program in the country.

Perhaps you should advise erstwhile math majors to switch to English.

I’m a little unsatisfied with your post. You’ve highlighted the key to success in the technical field – developing mathematical insight, physical intuition, etc. However, you’ve not actually told us how to do this. It is like my piano teachers telling me, “You must play that passage softer!” without actually showing me how to do it. I find your books and blogs rife with this kind of pseudo-advice, and I find it very frustrating.

What is a meaningful measure of how insightful you are about a concept? What techniques can be employed to ensure you’re gaining this “insight”? I can construct the wavefunction for hydrogen from scratch, but I don’t feel I have any “insight” into the myriad quantum numbers that fall out of the calculation.

Regarding your tips:

1. Reading the textbook may be helpful, but it’s very difficult to gleam what’s relevant on a first pass. In fact, I find that the most “insight” I gleam out of a book is when I pick it up again a year after last studying from it. Then I ask myself, “Why didn’t I get this stuff before? It’s so simple when I look at it now!”

2. It’s not always so simple to just “ask” the professor about what’s confusing you. Speaking personally, I find it difficult to ask meaningful questions in class when my mind is swirling with confusion, and professors have a bad habit of misinterpreting your question and going off on an irrelevant tangent for 5 minutes, further confusing and discouraging me.

3. It’s not as easy as “finding exactly where the problem is.” Have you ever had an unexplainable feeling of confusion? You know something’s not right. Something about the concept is bothering you, but you can’t place your finger on it, and so you can’t ask a meaningful question? What is one to do in such a situation? If I knew exactly where my problems lay, I would have them cleared up immediately.

4. This is the first piece of useful advice. I find review of notes helps clear up some of the confusion that was experienced the first time around.

5. Same as 3.

6. Again, what is a measure of “insight”? Sometimes I think I have excellent physical intution, and then I talk to someone and realize I don’t have a clue.

You can see my frustration, I’m sure. It’s not enough to present the challenge. One also needs to present the solution, and a means of gauging one’s progress.

I don’t mean to come across as harsh. Many principles outlined in your book and blog have helped me immensely, but these are mostly related to organizing my study time. I haven’t found much helpful advice on how I should best use that study time to learn, memorize, gain insight! into the material.

It may just be that I’m a stupid, slow learner, though. I wish not to have to admit that quite yet, though.

As I described in my follow-up post about my discrete math class, one way to solve this is later, when trying to write out the proof (or explanation) for a concept, you’ll identify exactly where you get stuck. You can then begin looking for information to get unstuck. You might start with the textbook or a web search. If still stuck, you’ll have a very specific question to bring to your professor or T.A.

Very good article! I’m wondering what tools you recommend for organizing and visualizing concepts. Do you find mind maps helpful here or something else?

This is exactly the philosophy with which I have approached most of my work (with variable success). You are not learning for the sake of a grade or any performance, but for what exactly says, that “deep down in your bones.” This is actually the foundation of learning anything, not just math. It is easier to see with math though.

@Adam, how to actually do this?

In my ponderings, the internalization of material comes through two things, active mental thought * TIME. You need to give yourself the time to sit down and just ponder/power through the material.

More insight on how to do this successfully? Approach everything, everything, with a sense of confidence, an absolute sense. You can learn the material, it will come to you, if you put in the requisite effort required (for me the effort to do this in a physics class is lower than a, I dunno, let’s say organic chemistry class, it was simply that way, different sorts of insights).

The thing is, if you approach it with confidence, that you can get there, you brain will be mentally prepared receive the information, be plastic enough to itnernalize it, and go to the efforts of time and concentration that it might require. If you don’t approach it with confidence, you might be just like “PV=nRT… right” and just keep going on and on… the best advice I can give is CHECK YOURSELF WHEN YOU ARE FALLING INTO THAT MENTALITY, take a break, get a drink of water, take deep breaths and hit the books again.

I think Cal has hit the nail on a lot of good tactic INSIGHTS into how to learn at the college level, but the more fundamental level most of us need learn our purpose/motivation in doing the things we do, and then attacking with full effort and confidence.

Hi Cal, I ran across this post — I completely agree with the philosophy and enjoy how you phrased it. When learning, I aim for those epiphanies where everything clicks and you don’t need to memorize symbols, you see the formula for the concept it represents.

Unfortunately, math is such a pyramid of ideas that if you have a loose foundation it becomes easy to lose insight for the subsequent topics. I definitely think there’s an element of mental perseverance to believe you can “get” it at an intuitive level, even if things aren’t clear now.

Unfortunately, in school it seems our rush to cover material means we can forget the higher purpose of what we’re learning (which isn’t to memorize and forget, memorize and forget 🙂 ). Anyway, great post!

Dear Cal Newport,

First, thank you for having written and published those two wonderful books of yours. Thank you, thank you, thank you. Secondly, thank you for your blog. Thank you so much. Third, I am a French student enrolled at UVA as an international student. I chose applied calculus as one of my classes and I’ve always struggled with mathematics, even when I was starting to like it. And , one of my problems was I did not understand the interest of what I was learning. What I want to ask you is, what I have been taught by my private math tutor and some of my math professors is that I have to do a lot of exercises, and being very focused. What do you think and what advices could you give me to ace my applied calculus class ?

Their advice fits, more or less, what I say above. You have to develop insight for every technique. Focusing very hard on an exercise, trying to figure out *why* you’re doing what you’re doing (and not just hoping to stumble into the right answer), and enlisting the help of your tutor/professor when stuck, is a good path toward insight development.

This art, as you call it (and I agree!), is what made me fall in love with the sciences, and what is keeping me right by its side. Because of my lack of efficient study skills, I’ve often skipped the insight phase. As a result, my grades went down and I began losing confidence in myself and my abilities. At times I wonder if the sciences are really right for me. Only time and a stronger commitment to effective studying will answer this question, but after reading your article, the insight phase is now something tangible, something I can grasp again.

Thank you so much for the advice you provide on your blog, it is so valuable and can still be so easily reached by many.

I think this post hits home. Speaking of which I did send an e-mail about how to study for Calculus(but i didn’t respond, sorry!)I’ve never done the insight step, but I have followed the tips. I guess I should follow this article when I retake Calculus

Related feedback from the philosophy department: If you give up math for philosophy, you’re probably still screwed. I teach philosophy. The students who do best are the ones who try to understand the issues at stake and why they’re at stake, rather than just trying to remember whatever it was that Socrates (or Hegel or Lucretius) said. The latter can barely do more than spit back at me whatever dead words were on a page or in their notebooks; the former are set up to think through the matter when I ask them what Socrates (or Hegel or Lucretius) would have said about x (or would have said to each other). It’s not easy, but IMO, working smarter up front means not having to work so hard later.

I was begin facetious. Philosophy classes were among the hardest I took at college. I’ve since studied it at a more advance level in graduate school (including Hegel, but not Lucretius), so I have a very healthy respect for those who do it well.

Thanks for this post Cal. I have your books and plan to go reread them before the beginning of my new semester. I’m transferring to a University this fall from a community college. I’m looking to get a Liberal Arts degree along with a teaching credential but am going to specialize in math. It’s not like I’ll be going into seriously hard math classes with only a specialization in math, but I thought I would start to read up on your technical posts anyhow. Here I found that this is something I do intuitively. I suppose that’s why I “get math”. It’s good to be aware of the process though and to use it to your best advantage.

Thanks as always Cal!

Ps. Cal, you should read “What’s Math Got To Do With It” by Jo Boaler. It’s a very fascinating book about how math is being taught in America and why we are producing so many kids that don’t “get math.” It’s interesting because your post does touch on part of that. Jo Boaler says that teaching kids simply how to do the equation and asking them to repeat the problem over and over again, just with different numbers, never teaches them what’s actually going on in the equation. As a result, students have a hard time doing problems that don’t have a memorized equation that they can apply because they really don’t know how numbers or equations really work.

Bravo. I think that this applies to all technical science classes, where you need to understand the relationship between different concepts in order to correctly complete the coursework. I’m still a highschooler, but going into Junior year, I think this is going to come in handy.

Once you have an “intuitive sense of what and why”, you know you have developed the necessary insight for a concept.

How much sample problems are necessary to ensure you won’t “freeze up”?

edit: how many

I know this comment is late, but it’s what I always try to get my students to do, and I like the clear way you layed it out. I remember how before I graduated someone asked me how I managed to get good grades on the tests in one of the challenging classes(linguistics attracts a lot of english majors who aren’t used to science)- my answer was just that you have to remember every single lesson during the semester, and understand how to apply it. Seemed like a pretty basic concept, there was no “trick.” I like your wording – developing insight for every concept introduced in lecture.

Yes! Yes! I have a math test tomorrow and this is exactly what I needed! Since the 6th grade I have thought that math was my weakest subject and so I would copy down every single little thing that the teacher explained…and when test time came all I had was a notebook full of formulas and notes that I couldn’t understand…I have been following this method until now and YOU made me realize my mistake. THANK YOU! You’re a lifesaver 🙂

Since I know the secret now, with a little insight and practice, I will ace my test tomorrow….and it will be the first math test I have aced in 7 years… I am SO putting this page on my favorites..

I’ve always wondered why all the smart kids in my class aced their tests…and whenever I asked them how much they studied, they told me that they didn’t study anything for the test. I was always confused b/c it seemed like I was working much much harder than they were…b/c I was practicing problems late into the night and I always bombed the tests, and was nervous and anxious on test day while they looked calm and collected.

maybe a bit late for me..next week, adv calc test, the upcoming week, adv calc, adv stats n linear algebra final exam..i’m dead

I was also confused about the math when I was in school.I think that’s the kind of question you’ll do better to figure out for yourself rather than have someone tell you.

After attending college (while working part-time) for four yrs without completing a degree,I entered the full-time work force as an Electronics Technician(wishing to be an Engineer). I am now nearing retirement with the hope of returning to college studies as part of my retirement. Because of the current economy, I will probably need to continue working part-time. Thus back to the same issues of not having the necessary time to do all the calculus homework to really get to an “a ha” moment. Anyone have any thoughts or comments?

There’s no real magic shortcut here. At the base level, for any subject, you have to identify: what is the understanding necessary to do well in this class. You can then search for the most efficient possible ways to build this understanding, but the time will still remain substantial for a tough subject.

If there’s not enough time in your schedule to match this requirement, then there’s not enough time.

I see formulas not as numbers and variables arranged in a function to arrive at a conclusion, but as the way that they appear in a graph. Would you consider that as insight? That’s for my Calculus classes at least. Doing this for Physics or Chemistry is MUCH harder.

awesome. rite on!

Good God, I wish I knew this from before. Now I understand exactly why I never did well in my Physics course despite doing hundreds of questions. Exam is in a few days… I suppose there’s nothing else to be done.

Cal I think you’re great but I think your answer to Wtldavis was a little dismissive.

Wtldavis as someone who has never taken an advanced Math class I’m probably not qualified to answer but as someone who took an FX makeup class that took a ridiculous amount of practice time (about 60 hrs for class, lab and practice)while working part time, I wonder if it would be best to take one class at a time per semester. I know that means it would take a long time to get your degree but it’s quicker than getting over your head and than quitting. Good luck I know what it’s like to be older and go back to school. 🙂

Wonderful post!

I need to think of how I can use it for my students (I TA in a statistics course…)

Speaking as a degree holder in both IS and philosophy and a person whose delivered enterprise-grade code, I feel I must retort.

I have often been asked “when do you use your philsophy degree?” My answer is

“Every day.” Many times, I wonder how people think clearly without one. Then,

one day, when reading yet another email from an engineering team that I was

supporting that was rambling, mentioned several facts but contained no directed

wish, and was non-sensical I realized: this is what the world to people

who don’t know how to argue clearly looks like!

This explains why so many engineers are treated as “trolls” by the suits. They

get trotted out for the dog and pony, but if you can’t explain the upside of

your area of expertise, then you will never advance beyond a tactical level.

Ask any engineer who’s made it big time (Technical Staff, Distinguished

Engineer), and this is the crticial skill between the alphas and the betas.

While much of the content of IS or CS degrees will change (SNOBOL versus

Haskell), the ability to reason, explore with tenacity, and structure thought

(arguably what programming also is, but in a human language), is a feature of

our condition and is unlikely to change.

It should also be noted that many philosophy degree holders are required totake symbolic logic. This makes languages (or notation systems) like the

lambda calculus or Haskell an exercise in the concepts already studied in the

pure abstract (noumenon, as we say) sans the luxury of a compiler to say if we

got it right!

Lastly, philosophy degree holders demonstrate a great deal of tenacity in the

pursuit of understanding structured thought. If you can stick through Being

and Time or the Critique of Pure Reason and derive the essential

insights located therein, you can follow a messy call stack

with the best of them.

Besides, CS is the study of a finite state machine, philosophy is the study of

the conditions of human experience, an infinite state machine 🙂

Regina scienitarum non deiecta est, amice.

Cal, you blew it.

Your explanation of the ‘intuitive’ side of differentiation is not good.

Qualification: Maybe your explanation is okay for an MIT ‘plug and grind computer scientist’, but let’s set those people aside! :-)!!

First, yes, in calculus and in nearly all of ‘mathematical analysis’ of which calculus is the most important part at first, ‘intuition’ is important. Really, for each good definition, theorem, or proof, there is a ‘picture’ (graph, diagram, etc.) that illustrates what is going on and makes much of the algebraic manipulation fairly obvious.

So, you are correct encouraging pictures.

Second, your picture omits any illustration of the role of h. So, you need to draw not just the tangent line but a few ‘secant’ lines, one for each value of h you want to illustrate.

Third, the derivative is a ‘local linear approximation’ to the function. Or, pick a value of h, remove the lim_{h \rightarrow 0}, rearrange, and get approximately

f(a + h) = f(a) + h f'(a)

which shows that as tweak h, f(a + h) gets tweaked by approximately just hf'(a) which is linear in h. Of course, the right side here has just the first two terms in the Taylor series.

That we are taking a limit here is crucial because we get the ‘chain rule’ that says, roughly, if we differentiate f(g(a)), then we get the local linear approximation of f evaluated at g(a) times the local linear approximation of g evaluated at a — when we differentiate a composition of two functions (here f composed with g), we get the product of the two linear approximations. This fact generalizes to where f and/or g is a vector valued function of a vector variable — nice since we get a product of two matrices.

This chain rule is especially nice since in the related subject of ‘calculus of finite differences’ we do not take a limit as h –> 0 and do not get a chain rule.

Here we see a secret: One good approximation to a complicated discrete situation is to ‘smooth’ the situation and use calculus. Can get some practical attacks on some NP-complete problems this way, etc.; some of these attacks are called ‘Lagrangian relaxation’.

Third, differentiation is linear: So with mild assumptions

(af(x) + bg(x))’ = af'(x) + bg'(x)

which is important. The two main pillars of analysis are continuity and linearity, and here we see linearity (again).

Fourth, what happens at a = 0 for f(a) = |a|, that is, the absolute value of a? Right: Without some ‘smoothness’ assumptions, there need not be a unique tangent to f at a. So, essentially everywhere in science and engineering where calculus gets used, we are asking for some ‘smoothness’ conditions. Such an assumption is more reasonable than we might think because every continuous function can be approximated as closely as we please by a function ‘smooth’ enough to be differentiable.

Fifth, the tangent, local linear approximation, and derivative get much of their importance from the fundamental theorem of calculus that if integrate f’ then get back f. A good illustration is to have f be distance traveled so that f’ is speed. Then if for, say, each second, multiply speed f’ by time of one second and add, get a good approximation to f. That is, at a, f'(a) tells us how rapidly we are ‘accumulating’ f. Or the speedometer tells us how fast we are eating up road on our way to our SO’s house.

Sixth, yes, in solving problems, first we have to guess at manipulations that might get us to a solution, and for good guesses intuition is crucial. But to do well on tests, still need to be able to solve the problems. One way to know that can solve lots of problems is to take a good sampling of the problems in the book and solve those.

Net, intuition does help and at times is crucial but is not sufficient.

@Steven:

Read the f*cking comments asshat. Cal clearly stated he was being facetious..twice.

This insight building phase was missed in the red book. In the red book, you said to forget the ideas and focus on the steady stream of examples presented by the professor. Then construct the mega problem sets, using the technical explanation questions. Even the technical explanation questions didn’t help much, accept to know the process of solving the problem. I focused on the problems in class and assignments, explaining the process of how to solve the questions via the TEQ. However, all i got was average marks. You should give better examples of how you made your TEQ, and how you developed insight.

This was missed in the red book. In the red book, you said to forget the ideas but focus on the examples presented in class. What you wrote, contradicted what you wrote in the red book. I focused on the example and problem assignments. I made my mega problem sets and the technical explanation questions to go along with it. The TEQ I made, required me to explain the procedure of solving the problems. The result, average marks. You should provide mores examples of how you went about developing insight, and some of your TEQ.

I had to take calculus for my job in 2010. I got it done.

Background: I got a computer science degree, in some sense, in the early 1980s. But, to avoid some money situations (drastic change of major to computer science, taking business calculus), and fear of “the” calculus due to a bad trig teacher…. So, I had to take “the” calculus. I got a bunch of dummy books, and a TI-89 calculator. My background of doing computer code maintenance for years got me through this. Those tests I took: calculators were not permitted. But, basic trig formulas were provided. Calc II course in the summer: we were allowed the integration formulas, only, along with trig identities. Of course,during that summer, I hired a lawn mower service and house cleaning service while I was taking calculus II in the summer’s 8 week course.

Key: Get to know classmates! Work with them. Get into study groups. Without my classmates, I would have not gotten my high A’s in calculus, probably gotten low B’s to C’s, without them for sure in calculus II.

In this day and age: get dummy/idiot books (I did), and read/work those problems as well.

Hey, no fair, I want to be a philosophy major! Haha but really, this post is spot on. I do, however, want to say that even though I’ve gotten over 100% in every math class I’ve taken (I’m currently a senior in high school taking AP Calc AB) because I’ve intuitively done pretty much what this post is saying, I really don’t like math that much. So while I do not panic or do poorly in my math classes (I’ve always had the highest grade in the class), I still don’t think of myself as a math person, and this is something that has always hung me up. I feel like I should think of myself as a math person because I do so well in math (and science) class, but a math/science/engineering focus in college really doesn’t interest me. What do you think?

@ an_entrepreneur

You missed the point. Why would Cal spend that much time/text explaining the derivative? A simple picture and an equation to show the difference works fine. Concept vs memorizing. This isn’t a blog about Calculus, it’s about studying. Here’s your math website -https://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/FUN.html#mathematics

Cal, great job on this post. I used most of the methods of your post already except making the list of the concepts. I’m in grad school right now and I’m feeling the “concepts flood” building a little too much in my QFT class. I just started making my list to help me out. Thanks again.

wow!,you have pinpointed the key to win in all these technical courses, but I still get confused about the concept–mega-problem sets, you mentioned above. Can you explain more about this?

In this grand scheme of things you’ll get an A+ for hard work. Where you lost us ended up being in your specifics. You know, as the maxim goes, details make or break the argument.. And that couldn’t be more true here. Having said that, let me reveal to you exactly what did give good results. The article (parts of it) is definitely rather convincing and this is most likely the reason why I am taking an effort to comment. I do not really make it a regular habit of doing that. Next, even though I can easily notice the leaps in reasoning you come up with, I am not really convinced of exactly how you seem to unite the ideas which inturn help to make your conclusion. For right now I will yield to your issue but hope in the near future you connect your facts better.

Isn’t it that the line should only touch one point of the graph?

It DOES “touch” only one point on the graph. It may “intersect” other points on the graph or “cut” the graph in places though. If it weren’t allowed to, continuous functions like the sine function wouldn’t have derivatives.

What if I am already behind in understanding concepts?

hey…. philosopy requires a tremendous amount of insight too. That click that happens when you finally manage to piece together the concepts of nietzsche.. its like a symphony.

Still, great advice on calc though!

Hey Cal, just wondering what your opinion is on how students should implement the quiz-and-recall method. At the moment, I’m using Anki primarily for its spaced-repetition system; I’m doing this by writing questions in and relying on Anki to schedule questions for me.

How does this method sound? Is there any software you’d recommend, or does pen-and-paper/word processing work just fine?

Thanks

What a load of BS

I know it’s many years since the article was written but I still read this one over and over as I try to get insight into basic maths (late high school , 100 level college papers). I don’t like the idea of just plugging numbers into formulas so really want to know what is going on.

Using the following as an example “A derivative at a given point is just the slope of the tangent line that kisses that point. Even more intuitively: it can be though of as the “steepness” of the graph at that point.”

I am unsure of this as intuition vs actually really understanding the formula. i.e to really understand the derivative intuitively should I know it as described above or know what every variable in the equation is doing and what would happen if one f those variables was manipulated ?

I know you’re just trying to put in a bit of good humor…. But you can still love philosophy and math. Descartes is the father of modern trigonometry; but let’s not forget he’s a philosopher too. I think the philosophy major is laughed on because it doesn’t provide any jobs besides teaching philosophy again. But I love philosophy. I want to be wise and live a beautiful life. And I want to share that beauty with other people. I changed my major from computer science to philosophy. And my grades in math were fine. ( All my grades were something to brag about.) But I chose philosophy because I wanted something deeper than solving problems we can step by step finding the answers to. I wanted something a bit more deeper, wild, and cosmic.

Great post! The only thing I disagree with is that philosophy is very similar to math. Both require you to have insight into the concepts before you can apply them. But grading tends to be easier in philosophy courses. Maybe that’s why you put them on different camps.

Yeah! It’s an helpful post. I feel like mathematician after getting this from. Now I understand exactly why I never did well in my Physics course despite doing hundreds of questions. My Exams are in a few coming day, I suppose that will be awesome. Thanks for sharing this great post.

Are there any procedures of questions to ask to ensure you understand the insights? How do you go about understanding the insights?

Great post, thank you! I feel that the insight piece is definitely what I was missing as I took my technical courses: ECON I & II, & Business Calculus. will definitely use the techniques suggested as I prepare to take my Business Calculus class, yet again for the 2nd time! I must admit that my lack of study time & attempting to take the course online was the worst mistake. This time, I will be taking it on campus & definitely invest a minimum of 10 hours of study time each while – all while frequenting the math lab at my school. This is the ONLY class I feel standing between me & my Business management degree. All of the other classes are relatively easier.

Cal, I am 52 and love your books..Wish I had them when I was struggling through physical chemistry. I got a masters in medicinal chemistry many years ago, but I changed careers and now a captain of a 240 ft supply vessel..OK..here is my request. All of these kids lives they have been in a sort of meritocracy.Hard work and it pays off with grades and recognition. But when they get into the real world its not a pure meritocracy anymore..They will all one day work for a blithering idiot that more often than not has an inferiority complex and resents intelligence.. If you dont believe me…look at any election or poll and the idiot leads and gets elected…Please write a book to guide these deserving champions on the pitfalls of post academia..Would love to hear your thoughts on this.

Warmest Regards

Dave

I think it’s very helpful because I’m new here and it’s the fiest time to learn something in English. This idea helps me to think in different way so that I can get used to studying here.

I actually do think practice problems can develop insight. Some concepts (e.g. quantum mechanics) are more about getting used to something than just having the aha. Also, doing practice problems can give you a little bit of a timeout from straining for insight and in the back of your mind, insight (“physical intuition”) may come. Furthermore, certain aspects of some problems may trigger the insight view–they may even be designed to do so.

So, yes, push for insight, sure. But don’t avoid practice because you “don’t get it”.

How can you practically apply this to teaching? Why don’t we teach the insights in our k-12 schools? How do you practically learn or teach insights for Pre-Algebra for example? Could you give a practical example for say how to teach the insights of a distributive property?

I think College is stupid, the professors are only money driven and it is all taught in a such a linear way. I definitely think College is a waste of time if you have a real passion that you want to pursue. I think any of you that say the misunderstanding of Calculus or mathematics makes people stupid or is a ‘weeding out’ formula you are wasting your breath. Math does NOT make one smart. What makes one smart is innovation, service and problem solving. You do not need math or college to tell you this, in fact if you have a passion for something work an odd job and find online courses that relate specifically to what it is you are looking for. This is the future of our generational learning, and College is full of linear learning programs that teach that failure is a painful thing and that when you fail you stay there, rather than a learning experience. They re-enforce this idea by making students take exams which actually do not help or aid in learning at all. I have friends who can back up my claim here but take it as you will. What is it YOU want out of life, what is it that you want to succeed in as much as you want to breathe? And besides why spend thousands of hard earned dollars on a stupid overpriced Linear Education system than pay hundreds on something that can actually benefit you?

Thank you for the post cal. I have a few problems with this as I have tried to put this process into action in my calc 2 class without success. This test came out to be a D whic was very disappointing (almost decided to quit trying to be a engineer) My process was a follows. Step accomplish all of my homework and write up study guides for a step by step process of what to do and why. Step 2 was to work on the even problem sets that were in the book for 2 days before the test. When I finished my test I thought I did B level work. Fast forward a week later I get my test back with a 65%. Upon looking at my test it appears that most of my intergrals were wrong I forgot some basic calc 1 material like the product rule in e^xy. With all of this happening I fell behind in my engineering physics homework. I would love some feed back as I’m really struggling to believe that I can do well as an engineer. As of right now I’m trying the Feynman technique to study for my next test on the shell method and work problems. Btw i am working about 20-30 hours a week and stressed out I’m doing poorly in my classes.

I am not Cal, but I think that classes like Calc 2 are more about solving problems than anything else, in a short amount of time. You should try to progressively restrict your time spent solving a problem to a shorter time, I used to practice on past papers in half the time.

I couldn’t agree more to this. The problem is that I’ve never been good at math, and I chose not to pick Math during my A level. That’s the reason I’m struggling in university now. I practice a lot for Calculus, by a lot I mean A LOT, sometimes for 8 or 9 hours a day. However, I always manage to get just average in the class. And this is just about Calculus. My CGPA is 3.71 and thats only because I had a C in Calculus. I know I should develop more insight about what I’m studying but while I’m here, with 6 courses, I can’t go back and start from high-school topics.

My advice: If you want to succeed in university, work your buts off in secondary school. University can be easier if you know your stuff. Good luck!

Simple insight isn’t going to give a person the capacity to do complex systems of equations and rearrange complex equations to figure a result. Some people just truly aren’t cut out for this stuff.

Thank you for the post as a mechanical engineering student this was insightful.

Insight is not just “helpful”, nor is it some platitude that would be wonderful, if only the world were perfect – no! Insight is the ONLY thing. The ONLY thing! IIf you are not 100% focused on reaching an “ah ha, I really get it now…” sort of epiphany, then you are wasting your time, the taxpayer’s money, the school administration’s efforts to help you be an educated person, etc. The Calculus represents the culmination of concepts in mathematics and geometry that had been gleened from the greatest analytical minds throughout the history of the known world. It is both simple and profound, and in that sense it is beautiful. If this is sort of lost on you, then make yourself learn to love it. There are vastly more satisfying ways to squander your youth than falling behind in a calculus class and struggling just to achieve a C-.

I love the soldier fighting back waves of concepts analogy. This article is sooo good. Now how to teach this concept to my kids……