Today is March 14th, which to us math nerds is also known as Pi Day, in reference to the first three significant digits of the mathematical constant pi (3.14).

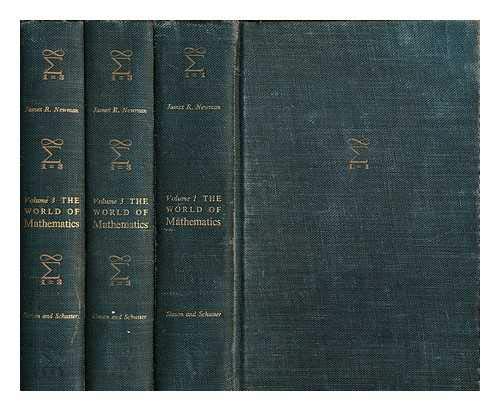

Part of what makes pi interesting is that it’s one of the most famous irrational numbers, meaning that it cannot be expressed as the fraction of two whole values (though 22/7 comes pretty close). In honor of Pi Day, I thought I would learn more about the history of irrational numbers, so I turned to one of my bookshelf favorites, The World of Mathematics: a four-volume history of math, edited by James R. Newman, and published in a handsome faux-leather box set in 1956. (I picked up my copy at a used book sale five years ago.)

The first volume contains an extended essay (originally a short book) titled “The Great Mathematicians,” written by Herbert Western Turnbull, the late Scottish algebraist. Turnbull dedicates much of the essay to great innovations from ancient Greek mathematics. It was Pythagoras (570 – 495 BC), he notes, who is most often credited for discovering that irrational numbers exist.

We know something of the proof that Pythagoras used due to a later account by Aristotle. The proof is elementary by modern standards (indeed, it’s a common example in undergraduate-level discrete mathematics courses). It goes something like this…