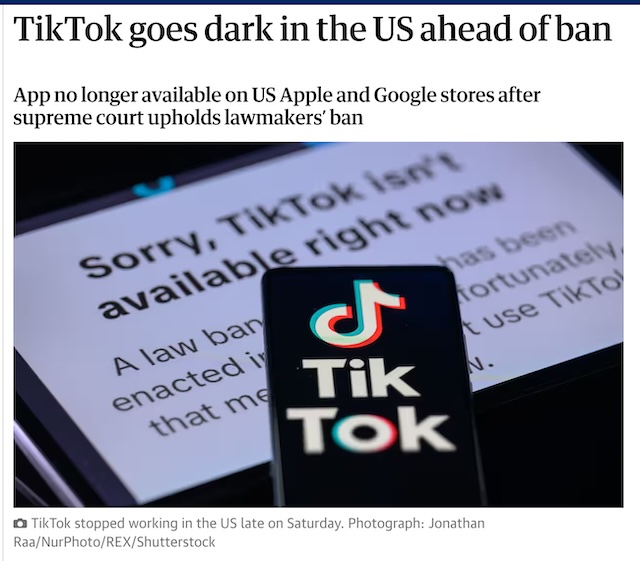

On Saturday night, in compliance with a law that the U.S. Supreme Court had just upheld, TikTok shut down its popular video-sharing app for American users. On Sunday, after an incoming president Trump vowed to negotiate a deal once in office, they began restoring service. It’s unclear what will happen next, as some lawmakers in the president’s own party remain firmly in favor of the divest-or-ban demand, while some democrats seemed to back-pedal.

From my perspective as a technology critic, the ultimate fate of this particular app is not the most important storyline here. What interests me more about these events is the cultural rubicon that we just crossed. To date, we’ve largely convinced ourselves that once a new technology is introduced and spread, we cannot go backward.

Social media became ubiquitous so now we’re stuck using it. Kids are zoning themselves into a stupor on TikTok, or led into rabbit holes of mental degeneration on Instagram, and we shrug our shoulders and say, “What can you do?”

The TikTok ban, even if only temporary, demonstrates we can do things. These services are not sacrosanct. Laws can be passed and our lives will still go on.

So what else should we do? I’m less concerned at this moment about national security than I am the health of our kids. If we want to pass a law that might make an even bigger difference, now is a good time to take a closer look at what Australia did last fall, when they banned social media for users under sixteen. Not long ago, that might have seemed like a non-starter in the U.S. But after our recent action against TikTok, is it really any more extreme?