The Deep Procrastination Crisis

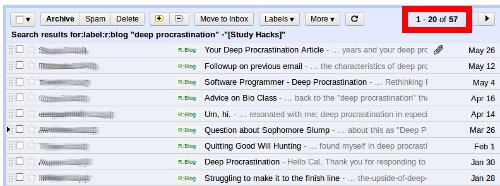

Above is a snapshot of my blog e-mail inbox, filtered to only show e-mails from students struggling with deep procrastination. Notice that there are close to 60 such messages. If I include blog comments in the search, the number jumps into the hundreds.

Deep procrastination is a distressing affliction. Students who suffer from it lose the ability to start school work. Deadlines pass and they hand nothing in. Professors provide special extensions, but the students still can’t bring themselves to do the work. And so on.

As evidenced by my inbox, this issue is surprisingly common, especially at elite colleges. Yet it’s also almost entirely off the radar of traditional student counseling, which is why I dedicate time to it here.

In my previous post, I introduced a dubious evolutionary explanation for an otherwise very real phenomenon: procrastination, in my experience, is not a character flaw, but instead evidence that you don’t have a believable plan for succeeding at what you’re trying to do. In this post, as promised, I want to apply this evolutionary perspective to help better understand, and therefore better combat, the deep variety of this common issue.

The Question of “Why”

Deep procrastination usually strikes students later in their college career, when the difficulty of their courses ratchets up. At this stage, their work load gets harder and harder, and at some point some powerful part of their brain says “no more!”

An evolutionary perspective on procrastination helps explain this reaction. The student is asking his or her brain to expend lots of energy (from a biological perspective, studying for an orgo exam is an expensive thing to do). One way to see this process is that there’s an ancient part of our brain that has evolved to evaluate any such plans — a filter, of sorts, to prevent the wasting of precious energy.

“Why are we going to expend so much precious energy?”, it asks.

The more modern, abstract-reasoning, rational part of the student’s brain is quick to respond: “Because we need to expend this energy to pass the test which we need to earn our degree!”

“What the hell is a ‘degree’ and why do we need one?”, the ancient brain counters.

“Because that’s what you’re supposed to do,” the rational brain responds.

And this is where the problem occurs.

The rational part of the brain is promoting an abstract societal value. It knows that for a middle class American, earning a college degree is an expected milestone on your path to integration into the middle class economy

But the ancient brain doesn’t do well with abstract societal values, which are a recent addition to humankind on the scale of evolutionary time. One way to understand deep procrastination, therefore, is as a rejection of an ambiguous, abstract answer to the key question of why you’re going through the mental strain required by the college experience.

(As in my previous post, I’m using an evolutionary explanation metaphorically — as a way to help explain a concrete phenomenon I’ve observed in my research and writing on this topic. Whether the evolutionary explanation for the phenomenon is strictly true is somewhat beside the point and beyond my expertise.)

The good news is that this understanding provides a clear strategy for combating this scourge: form a more concrete and personal answer to the question of “why.”

Combating Deep Procrastination

From my experience, an effective answer to this question of why you’re at college can be constructed through the following process:

- First, devise a (tentative) answer to the following question: What makes a good life good? This is the foundation on which everything else in your life will be built. Your goal is not the identify the “right” answer, but to instead identify a working hypothesis. This answer will evolve along with your life experience, so this is not a time for perfectionism. If you’re religious, your starting point for finding this answer is obvious. If you’re not religious, you could jump into philosophy — as this question has been at the core of human thinking since the time of the Greeks — but I’ve found it’s more approachable to start with biographies of people whose life you admire, looking for evidence of their own responses to this prompt.

- Second, decide how your experience at college can best be leveraged to support this vision of a good life. If, for example, you decide the key to a good life is to master something useful to the world, this might lead to you to see college as an opportunity to master a hard skill while exposing yourself to examples of people applying this skill in useful ways.

- Third, identify the set of specific student tactics that will help you succeed in this leveraging. In our above example, this thinking might lead you to the concrete strategies I espoused in my romantic scholar series.

This process provides a more personal and concrete answer to the fundamental question being posed by your ancient brain.

“Why should I expend all this difficult energy?”, it asks once again.

“Because it’s part of a well-thought through plan for leading a good life,” you now respond.

“Sounds good,” it agrees while you head to the library.

As I noted in an earlier post on this subject, this self-reflection is not an easy process. But college really is a fantastic time to face these basic questions. Deep procrastination, once you understand its source, doesn’t have to a Jobian affliction. It can instead be seen as the prompt you need to get your internal shop in order.

If you’ve had success combating deep procrastination with answers to these basic questions, please share your experience. Concrete examples help deep procrastinators commit to a way out.

I used to suffer a lot from this, although my degree is certainly of great use for me and my life goal. I think you re approaching the right point when you say that students suffer from procrastination at later stages of their studies. I recommend any student who feels familiar with the situation to examine exactly where the point is when you start doing other things (e. G. Checking Facebook) instead of studying. Try to jump beyond that. Just write that one sentence down. It will be good enough for now. Set yourself tiny timeframes and reward yourself with pauses, coffee, chocolate, whatever. A tight schedule and an exact plan will make you much more efficient and you will have time to watch sports with your friends or see your girl in the evening.

This is my experience and I implemented it after failing in more than three exams/essays. I had my best term ever.

I find the question of why very interesting. indeed, if there is no reason why, then why bother getting a degree at all? There are lots of answers, if you are genuinely interested in the material you’re reading, there’s not much of a problem. If you want to get a degree in order to get a particular job, then you’ll struggle more, but you can develop an interest and appreciate the value of the learning, even if you find it boring. If your degree is simply for the expectation of having a degree, because you can’t imagine not having one, or to please your parents, or just for money, that’s going to be the hardest slog.

“The Now Habit” is a very very good book for ending procrastination. The unschedule techniques and reframing “have to’s” as choices it a huge deal (and also helps say no to things you really should be anyhow).

It helped a TON when I used to have issues with this.

The Now Habit: A Strategic Program for Overcoming Procrastination and Enjoying Guilt-Free Play

Cal,

I consider the view you outlined in your previous post to be a subset of the well-documented phenomenon of people to procrastinate more over abstract tasks than concrete ones (my comment in your previous post has a summary of the research).

I see in your current post that you echo this by contrasting the abstract rational thinking of the ‘modern’ brain with the ‘ancient’ brain’s focus on immediate relevance and thus the need to form concrete plans/strategies to deal with this dichotomy.

It’s why David Allen (Getting Things Done) tells us to break large, nebulous projects up into smaller concrete tasks (we’ve heard this from many others but it’s nice to know there’s solid research that backs it up).

With procrastination I think there are two other major factors to consider (which are hinted at by your ancient/modern brain explanation):

hyperbolic discounting – the universal tendency to make more rational choices for actions due to take place in the future and less rational (or more contingent) choices for actions in the present. It explains why almost everyone would be willing to delay getting $100 in a month’s time in order to receive $110 a day later, whereas if you give the same people the choice to take $100 today or $110 tomorrow many would take the $100 up front.

the “Divided Self” – the notion put forward by Schelling et al that we do not possess a single unitary self but actually a collection of disparate selves which are competing with each other for attention and control at any given time.

The Divided Self Theory offers a radical solution to why we procrastinate: the ‘me’ that makes plans for the future is not the same ‘me’ that fails to execute them in the present. There is in fact a rational future-focused self and a present-focused self which are two antagonistic aspects of the divided self that constitutes us.

It solves at a stroke the philosophical conundrum of procrastination – why we do something which is inimical to our interests even when we *know* that it will ultimately make us worse off.

It also suggests that beating yourself over the head with the injunciton to ‘try harder’ is not a smart way of dealing with the issue.

There’s an excellent article by James Surowiecki from the New Yorker that explains all of this better than I can: https://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/books/2010/10/11/101011crbo_books_surowiecki?currentPage=all

(I posted this at the bottom of the comments to your previous post just before I saw you’d issued an update so please excuse me for putting it here as many would not have seen it).

My tip: Simplify your plan. The brain hates complex plans with lots of decisions. If there are too many moving parts, your brain simply refuses to sign off on it, leading to procrastination (not sure if it’s deep or not, I don’t know where the line is on that).

My favorite study on this: Ask doctors “You’ve seen a patient for [something they see a lot], tried lots of drugs and they didn’t work, and he’s scheduled for surgery tomorrow. Then you realize you forgot to try aspirin. What do you do?” Something like 90% say “postpone the surgery and try aspirin.” But if you instead say “You realize you forgot to try aspirin and [some other common drug],” only 40-50% postpone the surgery. The extra complexity of the plan made their brains say “Nope, not going to evaluate this branch.”

Your advice to try to answer “What makes a good life good” sounds just like your previous great article about thinking deeply about the lifestyle we want to have for our ideal life and then to plan backwards from that goal.

This really is a great method to consider your needs and desires in different areas instead of only our career.

I forgot to mention it, but a great book about overcoming not only procrastination, but also many other problems in your life is “Self-Discipline in 10 Days”. The author effectively and concisely explain how to develop self-discipline and use it in order to combat such problems. Highly recommended

Cal, I think that you should also look into psychological reasearch(especially recent research), about how to cure procrastination and the severe case of deep procrastination.

there are some great articles on PsyBlog about such research.

Any suggestions for good biographies of inspirational people? I was thinking Einstein.

Would be cool if someone gave me an idea here.

Newton, Einstein, Feynman are great examples of books to read.

Sometimes how one frames the work helps, I’ve found that having to prepare work for a friend or a colleague helps me get over deep procrastination. The social structure helps. Its too big to have ‘in 5 years I’ll earn X amount’ or even for me ‘I’ve an exam to pass’. Small goals and rewarding oneself.

99% of procrastination is not being able to find 1% justification for the action.

p.s. most students are just bored

I think this got me: “procrastination, in my experience, is not a character flaw, but instead evidence that you don’t have a believable plan for succeeding at what you’re trying to do”.

I’ve found that in general if you are always (a) well-planned and (b) have strong principles on how to make decisions then procrastination is usually not an issue. (a) is generally easy to set up, i.e. following Cal’s weekly booking system is one example of something that is reasonable to adopt.

(b) is always much harder. Partly it is what determines your ability to stick to the plans (part a), but more importantly it simplifies decision making, especially when the right choice is the more difficult path (i.e. study hard vs slack off). Putting this in the context of this article, it means convincing your ancient brain of your principles first, and then the rest just follows without much questioning.

For example, in the doctor study mentioned above, I think that part of the problem is that the doctors in the study deciding to still do surgery simply don’t have a strong enough of a principle regarding not doing unnecessarily expensive, dangerous, or time-consuming procedures.

As a student example, if you develop a principle that, even outside proper planning, that studying is the proper thing to do, then even last-minute studying comes easily (though typically it is avoided if you plan well).

Your explanation does not account for fear of failure, which I believe to be a very powerful factor.

Excellent prescription. What I’ve found to be an issue is that when one procrastinates, he’s procrastinating on something concrete, while the thing he wants (that’s supposed to motivate him!) is relatively abstract. According to Dan and Cheap Heath of “Made to Stick” and “Switch” fame concrete assertions are more motivating/compelling than abstract ones.

Thus, a possible strategy would be to attempt to make your why for doing the task, just as concrete as the task you’re procrastinating on.

I suffered from deep procrastination in my first year at university and subsequently had to withdraw and go to college. It took another 2 years before I started getting better. It wasn’t an easy task to get rid of deep procrastination, because you need to work consistently over a long period of time, and also be driven by some strong goal that gives you results and motivation from time to time. I still procrastinate on assignments here and there (I wish I didn’t) but at least in the big picture, I am very serious about school now as I want to get into medicine.

What is your answer to “What makes a good life good”?

Great post Cal, and I really enjoyed you covering the point of “What makes a good life good?”. In my experiences so far, and the readings of others, self-awareness is key to finding the perfect balance in your life. In Chris Lowney’s book, “Heroic Leadership”, he outlines how Jesuits went through ‘Spiritual Exercises’ which outlines self-meditation to figure out who you really are. Because before you know who you really are, you can’t figure out what you want to do with your life.

Just a tangent, but I really think that the idea of Vision->Goals->Planning could be a good topic for long-term goal setting and keeping the end in mind, and figuring out what you really want. Good post, keep it up!

Thank you for this. It’s been a while since I was a student, but my current research leads me to think that, for me, when Deep Procrastination hit me back then, it was my Fixed Mindset hitting the brick wall of what I could no longer easily absorb. The result was a paralyzing blankness that I only managed to get through (and get my degree) with brute force. Your way is not only much more likely to succeed, but its rational calm approach is more humane as well.

Armed now with the understanding of how mindset works (thank you, Dr. Dweck!) and working hard to cultivate a Growth Mindset, I can see how your solutions can be applied to many kinds of deep procrastination (with, in my case, a lot of scribbling on paper to work through your questions and suggestions).

I wish you great success in your new post.

Procrastination sometimes is also necessary, for the brain to change directions, so that when we return to focus on the task at hand, we will be more inspired/ refreshed?

Don’t you think ADHD is also responsible for deep procastination?

As an academic life coach, I work with high school students and help them prepare for college. I guide them through the college application process which is often filled with stress and anxiety. On top of navigating high school and trying to have a social life, students must also think seriously about where they want to attend college and what they want to do with their life. With all of these paramount questions, it’s only natural to want to put it all off or not think about it. From my experiences working with students, procrastination is at the forefront of the stress.

Like you said, determining the reasons behind procrastination is crucial. In a student’s case, being stressed about the college application has a lot to do with all the work involved in applying to college. To avoid procrastination, I like to design a schedule with my clients that gets them motivated, without being too overwhelmed. For example, rather than stress about the application for two days straight, spend two days writing down which colleges you are going to apply to. If you outline the process step by step and split up the project into small pieces, the work will be achieved without a daunting task!

There is a big difference between procrastination and deep procrastination. I totally agree that at this level, procrastination is more than lacking the requisite interest/motivation/discipline/study skills – it is something that takes root so deep that it is no longer in control of the rational self.

I dropped out because of deep procrastination from a course I loved. After a year’s break, I was ready to go back and finished by course with every single essay in on time.

I don’t know how I got through to my ‘ancient brain’ though – I think by virtue of a year’s self-analysis I bypassed those questions and was in agreement with myself as to what made me happy.

Don’t you think ADHD is also responsible for deep procastination?

No. I think that can lead to normal procrastination problems. The deep variety, however, touches on something deeper.

Hmm…

I am a recent college student who HAS no life goals. I find it difficult to put in any effort whatsoever. I am considering whether or not I should withdraw for a semester. If I don’t get at least a 2.0 next semester, I will be expelled.

The problem is… what would I be DOING for that stretch of time? How the hell am I supposed to figure out what I want to do with my life?

I swear, if I had a certain goal and I knew that I would need the skills taught in my particular major to ACHIEVE that goal, I would be much more motivated. Right now it feels like they are just throwing random facts and information at me… and I have no desire to catch them.

Overworking students is a fantastic way to cause deep procrastination. One, you can only work so hard before you start going insane, and switching activities without switching topics is not the same as a real rest. Some programs do not allow enough time for students to rest.

Two, because with too much work and too many projects it is very hard to stop and think plans through, because the plans are too big and scary, and making them takes time you could be working in. Trying to plan how to handle a semester-long design studio project can give you a panic attack: the amount of stuff you have to do is so overwhelming and your time so limited.

I still need to practice making plans and then blocking out the stuff that’s too far ahead. You have to have some sense of what’s ahead to succeed, but if you focus on it too soon you won’t be able to get today’s work done.

Your deep procrastination is what others have simply called indecisiveness. There is a small, out of print book, Overcoming Indecisiveness that provides some very useful help.

Overcoming Indecisiveness stresses that the most important aspect of decisiveness and achievement is the commitment to following through on what you decide; your point here that having a believable plan for achieving your goal is an obvious and very important extension of that idea.

Procrastination basically is a problem in affective forecasting and having no implementation intentions.

Is deep procrastination in a 16 year old female simply defiance? All thoughts appreciated!

For the first time in my life, I am experiencing this. And it’s not so pleasant.

Now instead of beating myself up and feeling guilty, I understand why. Thank you!

I wish your site had been around when I was in school – I think I would have paced myself better and given myself some breathing space. And not worked so hard to convince that little part of my brain that I needed to do something “because you’re supposed to.”

Do you have any posts with advice on how to keep to a schedule? My work is in social media and I find it hard to focus and build incremental progress in one area vs hopping from one area to another.

Wow. I’ve been going completely insane for about a year now with exactly what you described as deep procrastination. I have maybe 12 credits left in college and I don’t think/plan on ever finishing. I had articulated exactly your thoughts of the brain saying what’s the point, and likened it to hitting the wall in marathon running. My thought was kind of that I always hated school, and being 20 years into an institution that I hate, at some point becomes intolerable. My whole life, I never attended school, I always crammed the night before, even in elementary school, and at some point in college with courses like stats and calculus that model doesn’t work. It can be done, but the information your tested on doesn’t exist in the textbook. Anyways, it was nice to hear the issue written up in an academic way and I am now going to further research it to come up with a better life plan. Thankyou

I have never in my life been compelled to

leave a comment on a website. I am in my 2nd

year of university and I struggle with procrastination.

This website is an inspiration to all those who want to beat the beast and succeed in life. I learnt that to succeed you have to have a plan, a solid, realistic plan you believe in with all your heart.

Thank you Cal and the fellow writers for the advice.

Thanks for writing about this, I feel much better reading about it. Thought I was going nuts struggling with absolutely horrid procrastination. I´m studying but also working full time in a creative job in the day and recently hit a complete wall with my university work. It was if my brain was just shouting no! No more assignments please. It didn´t matter if it was something I would usually enjoy and could have written in a couple of hours. Anyway, I have no excuses as I chose to do this course. I find having a good cry helps.

Procrastination has been a major problem for me. With the help of you advice I intend to give it up next week or soon after.

I think Stephen Covey said it best — “just say no” Many times people procrastinate because of outside influences.

It’s still hard to cure deep procrastination after use your method.

thank you. I always knew my procrastination wasn’t just out of laziness, telling myself to jjust work ended with me arguing with myself internally and I’d wasted time and felt like crap at the end. I will try this, and thank you for a proper explanation.

Cal, you are awesome. Thank you.

I suffered from deep procrastrination in the first 2 years of my Ph.D. I always had the dream to become a researcher. This was the motivation behind all my earlier hard work, so when I finally did become a researcher (or a researcher jn training), it became harder to find a good motivation.

Furthermore, I found out I have ADHD and the change of work environment (from home to the university) meant I suddenly couldn’t concentrate anymore and I couldn’t get any meaningfull work done. I put in hard effort every day, but despite that I couldn’t get started on my research. My effort was not awarded with meaningfull results, so eventually I couldn’t find the motivation to get started any more. A change of my work method and working at home instead of at the office did the trick. At the moment I’m very happy with my research (third year of the same Ph.D. project).

I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently. I see this as the important question of drive – what drives you?

What drives me is the fact that we have limited time on earth, so as someone once said, instead of counting the days, we should make the days count. If we lived forever, there would be no hurry to get things done, since there would always be tomorrow.

While this is a great abstract answer, what helps me is something a lot more concrete: habits. As you write yourself fixed-schedule productivity can help cure deep procrastination, since you say to yourself, no matter what, I’m going to keep working on this from 9 AM to 5 PM every day.

But what if you are really burned out?

Feynman, Nobel-Prize winning physicist, shares this story where he, too, got burned out. He resolved to just play around with problems, regardless of whether it was important for the future of physics. In another interview, he shares that what drives him is curiosity.

At the end of the day, you can have these cool tips and tricks, like forming habits and trying to make each day worthwhile, but at the heart of it, you have to be interested in your work. In other words, focus on the work instead of these abstract considerations (kinda like what Newport is advocating for in Being So Good That They Can’t Ignore You).

I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently. I see this as the important question of drive – what drives you?

What drives me is the fact that we have limited time on earth, so as someone once said, instead of counting the days, we should make the days count. If we lived forever, there would be no hurry to get things done, since there would always be tomorrow.

While this is a great abstract answer, what helps me is something a lot more concrete: habits. As you write yourself fixed-schedule productivity can help cure deep procrastination, since you say to yourself, no matter what, I’m going to keep working on this from 9 AM to 5 PM every day.

But what if you are really burned out?

Feynman, Nobel-Prize winning physicist, shares this story where he, too, got burned out. He resolved to just play around with problems, regardless of whether it was important for the future of physics. In another interview, he shares that what drives him is curiosity.

At the end of the day, you can have these cool tips and tricks, like forming habits and trying to make each day worthwhile, but at the heart of it, you have to be interested in your work. In other words, focus on the work instead of these abstract considerations (kind of like what Newport is advocating for in Being So Good That They Can’t Ignore You).

My deep procrastination has affected everything in my life – it started with schoolwork, then started to make me feel debilitated when it came to washing dishes, doing laundry, or dropping off a package at the post office.

I find it helpful to address the underlying fear/anxiety/worry that is preventing you from doing the task. Mantras like this one help me make it through every day: “Deep down, I’m worried that I won’t score high enough on this paper to boost my grade to passing, which has been preventing me from trying. The due date has already passed, so I’m embarrassed and worried that the professor will ask me why it’s late, a fear which has made me avoid going to class. I’m anxious about my ability to write a good paper. Bigger than that specific fear, I’m worried that I’ve fallen behind in every class, and I don’t know how I’ll pass. Acknowledging all of these underlying reasons, I realize that, though writing this paper seems insurmountable at this moment, I CAN do it. This task is not representative of anything – it’s just something I need to get done.”

Rationally talking out or writing a statement like this out helps because you’re addressing the deeper reasons for your procrastination. Just like we avoid our work, we can avoid addressing those deeper fears, and just push them down and out of mind.

Just want to say, thanks for the posts. I found this blog yesterday, and i think it’s informative and helpful. The problems you addressed through this blog applies to many people. Wish to read more. I am a phd candidate by the way. so thank you!

; )

I really liked your idea to ask yourself about vision of the good life and then think about student tactics that will help. One more useful tip I use very often is drawing a workflow of your project, of your plan to achieve a goal. It helped me a lot as I saw the big picture. I used https://casual.pm to plan my tasks like visual maps, hope it will be useful for somebody.