A Focused Digression

David Brooks’s most recent column ends up on the subject of geopolitics, but it begins, in a tenuous but entertaining fashion, with a long digression on the routines of famous creatives (which Brooks draws from Mason Currey). For example…

David Brooks’s most recent column ends up on the subject of geopolitics, but it begins, in a tenuous but entertaining fashion, with a long digression on the routines of famous creatives (which Brooks draws from Mason Currey). For example…

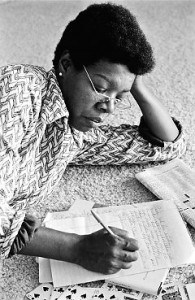

- Maya Angelou, we learn, was up by 5:30 and writing by 6:30 in a small hotel room she kept just for this purpose.

- John Cheever would write every day in the storage unit of his apartment. (In his boxer shorts, it turns out.)

- Anthony Trollope would write 250 words every 15 minutes for two and a half hours while his servant brought coffee at precise times.

To summarize these observations, Brooks quotes Henry Miller: “I know that to sustain these true moments of insight, one has to be highly disciplined, lead a disciplined life.”

He then offers his own more bluntly accurate summary: “[Great creative minds] think like artists but work like accountants.”

Or, to put it in Study Hacks lingo: “deep insight requires a disciplined commitment to deep work.”

Keeping these insights in mind, now consider the following article posted on Time.com the day before Brooks’s column: 9 Rules for Emailing From Google Exec Eric Schmidt.

The piece offers an excerpt from Schmidt’s new co-authored book, How Google Works. Here’s the first piece of advice it offers:

“1. Respond Quickly. There are people who can be relied upon to respond promptly to emails, and those who can’t. Strive to be one of the former. Most of the best—and busiest—people we know act quickly on their emails.”

This juxtaposition represents a trend that puzzles me.

We know, as Brooks observed, that brilliant creative work requires repeated long periods of uninterrupted depth.

We hear often that brilliant creative work is incredibly valuable in our current business culture.

And yet this same culture ignores depth and continues to glorify connectivity (as Schmidt exemplifies).

(Some might argue that you can do both, spending most of your time responding quickly to communication, then carving out additional time to go deep when needed: but the research shows our mind doesn’t work that way; and most people probably intuitively understand this.)

To explain this trend, it might just be the case that in business, the impact of constant connectivity on one’s marginal productivity outpaces the impact of deep work.

But at the same time, if one is feeling a bit cynical, it might seem like a lot of this preference for connection over depth is due to the fact that although the Eric Schmidts of the world like the idea of creative insights, in the moment they like even more the convenience of getting a quick response to their messages.

And I would suspect that Maya Angelou was probably terrible at e-mail.

I think Matthew Crawford explains why this happens in Shop Craft as Soul Craft. Basically, in the absence of objective standards of performance in a corporate job, the organization will move to fill in gaps with arbitrary standards, like “being visible” or “responsive” that has more to do with being likable and not being blamed than on doing good work (which is not easily identifiable).

The “deep work” at large companies then, if your work can’t be measured by objective standards, involves tasks like answering e-mails quickly in order to look like a responsive and likable person.

Thanks for this. I read Schmidt’s article and felt a little uncomfortable with that idea…you provided a great balance.

This is a very interesting juxtaposition of ideas and I have done both. When I wrote my book Surviving the College Application Process, I worked like Maya Angelou. I set aside at least an hour a day every morning without fail in a quiet, uninterrupted zone. The discipline of having the time to write, helped me tremendously in producing the final output. But as a business person running an educational consulting practice, I am known for providing quick responses to my clients. I don’t know if the two have to be mutual exclusive, however, they have to co-exist at different times in the day. What this blog post brings up is the need for both the quiet, uniterrupted time and discipline to create, as well as the ability to keep up with the fast-paced need to response quickly to others.

I think it depends what position your are, entry level or at the top. If you’re entry level your superiors want you to get back to them as soon as possible because it keeps they’re work going. However if they are the ones that need to respond they probably find they have more important things to do.

I think you are right, but this puts an interesting contrast to the value of work from both individuals. The senior employee feels their work is more important, therefore the junior should drop what they are doing to respond to the needs of the senior employee – they are able to maintain the mind-space to keep focus, but the junior is now forced to jump from task to task. There is a congnitive loss for every task you switch between, so the junior’s performance will decrease the expecation of responsiveness. One then needs to consider the value trade-off in lower performance from this employee.

I have to wonder how many e-mails Schmidt recieves in a day that distract him from the work he is doing? Or perhaps more to the point, when does Schmidt create time for his deep work, and when does he expect other Google employees to do the same?

Great observation Mariya.

Additional thought: Most managers “like” the convenience of quick answers, but they respect and reward the focused and disciplined employees.

Your “juxtaposition” rests on the assumption that what Eric Schmidt is trying to do is “brilliant creative work”. Are you certain of this assumption? Eric Schmidt is a manager, a large part of his job is basically communications — keeping the human machinery of Google running. He’s not creating new algorithms or designing new interfaces. For someone in that position, fast and clear communication is absolutely crucial (see #2 in the article). He probably has certain chunks of time devoted to “administrative deep thought” — how to deal with a difficult supplier or government entities, what new areas to expand into, how to treat underperforming areas of the company etc. etc. But (1) this is pretty different from creative deep thought and probably depends a lot on communication as well and (2) he can do this later at night or early in the morning when email activity is low.

Also, I seriously doubt that Eric Schmidt has fixed schedule productivity and stops work at 5:30pm.

Well said.

Cal, I think you’ve made many embedded assumptions here as Shrutarshi points out. I’m not sure I agree with them.

If I may play both cynic and devil’s advocate, it feels a bit like you’ve been looking for confirming information to validate your own thesis on email of late.

While I do not disagree with the overall idea of being careful about letting email and social media take over your schedule, I think there’s a lot of gray area here and I think your engagement will depend on your occupation, role, culture of the firm you’re in and level of useful collaboration required.

Many of your examples focus on authors and researchers, who like you, need to churn out a larger proportion of work individually. That is not the case in companies. While you can argue that a lot of collaboration is unnecessary (I’d be the first to agree), there’s large parts of it that are critical. And, teams break down with a lack of communication.

The individuals used in your post had creative occupations far too different from that of most corporate types to be a valid point of consideration. Even in professions that emphasize creativity (advertising copywriting, photography, etc.) the emphasis these days is on speed and responsiveness rather than depth. There may be moments for the kinds of deep reflection that result in the most creative solutions…but that time is too often few and far between.

Historically there have been some companies that have tried to provide employees time for “deep thought” (though they wouldn’t have called it that). The results were often good, but the cost of having those employees outside of the “traditional” corporate stream of activities was not outweighed those results.

Certainly the ideal situation would be one that allowed for deep thought, but the professions in which that is valued is on the decline. Even in the academy (the place that deep thought should absolutely reside) we’ve seen that growing sense of “respond to everything immediately” culture grow considerably in the last several years.

This thread is important. I write sharp posts about communication technologies because I worry we don’t sufficiently debate how and why we use them, and instead tend to back fill explanation once a use pattern has emerged. Discussions like the one represented in these comments are therefore really important…

To speak to Mariya’s point, I agree that position matters if you’re trying to advocate for more depth in your work routines. You need career capital before you can demand special treatment. (In some sense, however, I’m trying to separate here the issue of what is the best way to work, and what you, as an individual, can realistically do to act on these answers.)

To speak to Shrutarshi’s point, I agree that high-level executives have unique demands. It probably would be a waste of money to take someone like Schmidt and force him to spend all morning thinking in a dark room. That being said, Schmidt’s book is not about his habits, but is instead about the company culture of Google. In my post, I wasn’t arguing that Schmidt’s e-mail habit is flawed, but that his suggestion that this should be part of a broader company culture is flawed. Google’s most important employees are engineers. A strong argument can be made that they’d produce more valuable results if they had more depth and less distraction. Notice, this is different than saying, “engineers should never communicate.” I’m instead noting that there’s a middle ground between, “strive to answer every e-mail as quickly as possible” and “work in a cave.”

To speak to Rohan’s point, (first of all, I should mention that I know Rohan and am always impressed with his thinking on such matters), I’m interested in the connection between e-mail behaviors and team coordination. I agree that in the absence of communication, teams break down. But do teams require constant e-mail checking?

Someone pointed me recently to this fascinating article where one of the engineers on the Apollo program talked about how they successfully organized their teams in an age before e-mail.

To speak with Jason’s point, the things you mention in your last paragraph are true, but I think are also really worrisome!

Who adds more value to an organization? Is it deep thinkers or the people (like Eric Schmidt) who organize them? Who gets paid more? Why is that?

To focus on CEO’s (how valuable are they? how should they act?) is not that interesting. It’s too small of a group with demands that are too idiosyncratic to generalize. The interesting question is how should the bulk of knowledge workers act.

I think we (in the generic cultural sense) know less than we might imagine about this question. It is difficult to measure marginal productivity in a knowledge work scenario which in turn makes the questions of “how to work” much harder to tackle.

(I couldn’t tell if you were being sincere or sarcastic with your questions, but assuming you were being sincere, the specific question of why CEO’s get paid so much is one that has generated a lot of really interesting debate among economists recently. For a while, the standard response leveraged Sherwin Rosen’s superstar economics. Corporations are so big, and the impact of the CEO is therefore so consequential, that even small advantages in leadership offer a huge financial advantage to stockholders, and therefore the very best deserve a huge premium, much in the way that the very best basketball player gets paid ludicrously more than a basketball player that is just slightly worse. Recently, however, Thomas Piketty has been pushing back against this interpretation. He argues that the rise in American CEO pay comes from two things: (1) it is difficult to accurately assess how much value the CEO actually brings; and (2) top marginal tax rates are currently quite low in our country. He argues that item 2 inspires top executives to stack the board, negotiate heavily, and otherwise do whatever they can to raise their pay [back in the days of an 80% tax rate, why bother, but with a 40% top rate, it’s worth it], and item 1 enables them to get away with it. There’s a lot of push back on this theory, especially among more conservative economists [as you might expect given that Piketty concludes we should raise taxes], but even Piketty’s strongest critics seem to agree about item 1, which I think has relevance to our discussion of work habits.)

I didn’t intend to be sarcastic or sincere, just thinking out loud. Both Maya Angelou and Eric Schmidt are on the fringes. The great mass of people are in the middle. Most of them could benefit from thinking more deeply but almost all of them have to spend most of their time collaborating. It may be that the collaborators add the most value. We’re all grateful for the wonderful work done by the deep thinkers but in the end, nothing gets done without collaboration! What do you think?

I think this is an interesting point.

I think an argument could be made that something about the nature of knowledge work and digital network connectivity makes frequent collaboration a huge competitive advantage. But then again, an argument could be made that this habit is overblown.

What’s difficult but intriguing about knowledge work to me is that all of these questions are really quite open.

I think you raise an interesting question. I would suggest that there needs to be structured time for all employees involved in knowledge based work to do both collaborate, and to do deep work. Deep work will be limited in the amount you can do in a day – this is why many authors and creatives will only get about 4 hours “work” done in a day on their book/art/creating, and then spend the remainder of the day doing other work like dealing with e-mail and meetings, and other communications. I know my work place has experimented with “meetingless Wednesdays”, but in the end, that needs buy in from all management. The same would go for e-mailless times – inevitably you have that one or two managers who don’t trust the system and demand their own needs be filled over those of everyone else.

The best collaborators need time to see how the patterns work and the pieces fit together, and this comes from having time to find creative flow (i.e. deep work). One can’t happen without the other. And I wonder, shouldn’t everyone be allowed the flexibility to structure their time to be most efficient?

I’m considering blocking out time in my day where I disconnect from my e-mail at work for key times I need focus. I’ll try it for a few weeks, and let you know how it goes.

Great post.

It makes me think of Paul Graham “Maker’s schedule vs. the Manager’s schedule”

“Most powerful people are on the manager’s schedule. It’s the schedule of command. But there’s another way of using time that’s common among people who make things, like programmers and writers. They generally prefer to use time in units of half a day at least. You can’t write or program well in units of an hour. That’s barely enough time to get started.”

https://www.paulgraham.com/makersschedule.html

This is a great reference!

I wasn’t thinking about Graham’s essay, but I think it provides insight into this conversation. Schmidt’s devotion to rapid connectivity — as many of you noted — likely plays a useful rule in the rarefied realm of top-level management. But Google is a company built on makers, for whom acting like Schmidt might be disastrous (just as Schmidt acting like a start developer would be equally disastrous).

So perhaps the right conclusion here is that we should be wary of universal prescriptions when it comes to work habits of this type, and instead really put in the time to try to uncover what makes the most sense if the goal is maximizing each individual type of employee’s value.

Do you guys buy this?

Can I suggest that the number of knowledge workers who actually do (or need to do) deep work in the way that, say, Cal does is actually very small?

At first glance, my job (what I am supposed to produce) is classic deep work – I write texts which explain cutting-edge architectural concepts, designs, and ideas to people who are not architects (and get them excited about the project). In reality, there’s very little of my job that absolutely requires the uninterrupted focus of deep work (perhaps a handful of hours a month). My real job (ie what makes it possible to produce good work and build career capital) is to facilitate the conversations and relationships that make it possible for me to understand these concepts and then put them into words that others can understand (without the benefit of someone hand-talking and sketching in the background). This means that I am most effective by maximising my availability – and yes, this means replying to emails swiftly, never being unavailable, and following all of Schmidt’s rules for good email.

Likewise, the majority of my architectural colleagues are not doing deep work either – perhaps 10% of our staff are deep workers whose job is to solve tricky problems or come up with profound ideas, and behind each of those is a dozen or so ‘knowledge workers’ whose job is to implement those ideas effectively according to accepted conventions. I would imagine that the set up is not so different at other ostensibly ‘maker’ environments (such as Google), where a small number of deep workers (the guy that came up with the idea for gmail) are backed up by a wider group (the team of engineers who write the code and keep it up and running and connected smoothly to everything else) who at first glance seem to have deep work responsibilities but whose jobs are in fact to support and enhance the value of the work produced by those deep workers.

I would go so far as to suggest, in fact, that you can tell you are a true ‘deep worker’ rather than a ‘knowledge worker’ because when you (like Cal) ignore your email (or make your calendar unavailable in large, frequent blocks), no one complains. No one complains because they know that silence from you means that great work is on the way; the rest of us are in fact responsible for being connected and responsive because that’s what we do – connect and respond to our ‘deep workers’ whenever they’re ready to connect.

I agree that it shouldn’t be universal, and I think it takes some skill and experience to figure out where deep work vs. shallow work come in. I’ve read both SO GOOD and am nearly finished with Getting Things Done, and I think they’re must-reads for any knowledge worker.

I think one key difference between a creator like Maya Angelou and someone in a corporate environment is the type of contributions they make. A corporate worker might have one or two projects that take creativity and insight, but there are usually a dozen or more projects that primarily require coordination and communication to achieve the goal. An author or academic may have many small administrative tasks as well, but everyone agrees that their valuable work is their writing or research, not how well they organized a book signing. In my job, I have a couple projects that I find deeply exciting and that could prove to be valuable, but the “deep” aspects come in at the beginning and at various points along the way; the majority is filled with communicating and coordinating, and sometimes cajoling and persuading. My value is largely measured by my ability to execute quickly, but also partly by good insights and thinking. I wouldn’t be surprised if the majority of corporate workers who are not engineers and programmers experience the same thing. I don’t think it’s the best way for a corporation’s bulk of employees to work all the time, but I do think it’s the reality.

I haven’t read Schmidt’s book, but I can see some of the appeal of instant replies: I am constantly waiting on responses to requests, sometimes for weeks, and in many cases I can’t get any work done on a project until I have been given what I need. I assume that most corporations and companies deal with hold up due to access restrictions. I need to find a publication on protocol implementation? I need to send a request and then three days later I’ll get the article. I need access to a database of metrics? It’ll take three weeks to get my access built. I think most companies tend towards limiting access for liability reasons, but it still slows work down and increases the amount of communication and email sent around. Maybe that’s unique to my field, but I doubt that it is. I’m sure there are a vast chunk of knowledge works who would love to get more deep and meaningful work done but are instead waiting on someone else.

I also instantly thought of Graham’s piece. To me the interesting part is how you reconcile the two different kinds of activities and time — because I think most of us have both — at the individual and the organizational level. The latter seems substantially more complex, and in my experience is a case where intentionally oversimplified heuristics (office hours, no-email days) may be more successful than optimized arrangements that end up being more fragile than they seem.

The other takeaway I have is that an overall commitment to fast responsiveness is far more costly than it may seem at first glance — and it’s a lot easier to get pushed in that direction by external forces. Also, I think we’re collectively guilty of overestimating the value of a fast response, even though quick email replies and the like often end up slowing down the process of getting to the desired result rather than speeding it up.

Great stuff to think about!

I think the most telling thing is that Schmidt equates the term “best” with “busiest;” as though the two are almost synonymous. In that sense then, a person should quickly respond to emails, texts, phone calls, always have their smartphone on and ultimately never stop being busy. All of those things are easily quantifiable and have been mistakenly substituted in as a definition of “best” because they are easy to measure and examine. That’s not how quality work is accomplished though, in any field be it carpentry or computer science. High quality productivity is a by-product of skill which is itself a by-product of practice. I would go so far as to say that busyness kills quality.

A colleague of mine on a project was incredibly fast at responding to emails, and often his timestamps read into the early hours of the morning, he was also very fast at designing and assembling the circuit boards we needed. He would spend hours and hours and hours at our projects’ work area, sometimes even sleeping there. He moved so fast that my colleague often skipped design reviews and sent his schematics out to be manufactured; Manufactured with critical flaws. Flaws that could have been identified and fixed if only a few extra moments had been taken to slow down. One board had incorrectly routed grounds that rendered the board inoperable, another had the connectors oriented the wrong way. The majority of the project’s budget ended up going to my colleague’s aspect of it, and the majority of that went towards having to re-manufacture boards. It was sloppiness writ large, and a by-product of the mistaken belief that busyness equals best.

There are two threads that seem promising here. One, Graham’s distinction between makers and managers. The other, a possible distinction between types of productivity.

At heart, we want more productive knowledge workers. That might mean getting work done faster. Or it might mean finding insights about ways to get work done far more effectively.

I’m doing a lot of instructional design at present. And I find I need both kinds of productivity. When the path is clear, I need to produce design at a good clip which often means exchanging email with people who can clarify needs and resources, can give feedback on phraseology and activities, and the like. It can often mean quite a bit of back and forth.

And there’s another kind of work, where I need to ask, for example, whether the overall curriculum design is the most efficient way to teach the material or whether the teaching could be rearranged, cut, put off, or approached completely differently. Sometimes those changes make leaps in the efficiency of the project as a whole.

That latter kind of examination takes concerted concentration for me. It gets interrupted and slowed by things like email and IMing. And at worst, it doesn’t get done at all because people never break from the constant churn of responding and engaging in the quick back and forth.

Answering an e-mail “quickly” is not the same as answering it “immediately”. You can put aside a certain amount of time for e-mails, say, at the beginning and end of each day, and ignore them for the rest of the day.

People usually figure out that they should call, text, or IM if they have an emergency.

If need be, you can answer a complex e-mail with a simple acknowledgement that you received it, and will send a more in-depth response at a later, established time. Then you block out some time in your schedule to write that longer e-mail.

I’ve worked in health care and I see this method widely used in that field– both by doctors who have secretaries to sift out the most urgent missives, and by fellows who must do it all themselves.

I agree, I treat email as it has always been intended, as an asynchronous form of communication. If people need immediate assistance they should call.

When I do answer emails, I try and handle them once only. Reply immediately, delete, or flag as task to be completed.

One of the myths about the post-industrial economy is that it has given more workers the freedom to be more ‘creative’ and do more ‘meaningful’ work. The Time magazine doesn’t describe how Eric Schmidt works – it describes how people who *work for* him work. It shows that even champions of this new age such as Google still want their employees to ‘respond quickly to emails’ rather than engage in deep and meaningful work that has a personal or creative touch.

I’ll bet Eric Schmidt is just as bad at answering emails as Maya Angelou. I also agree with Cal’s sentiment that the ‘deep work’ approach, as opposed to ‘answer emails ASAP’ is the *only* way to do creative work.

While I wouldn’t get rid of Cal’s blog, there is an oversupply of ‘productivity optimization’ advice out there. While many under qualified people consume this type of advice, in reality it applies to very few people. Most of it serves merely as propaganda aimed at people like Google employees that gives them the illusion that they are more than a cog. The key to even their productivity is, above all, brute force, more sweat, and longer hours.

It really depends on the context. It depends on the line of work you’re into. Most of the work done in an economy is NOT deep work.

It’s more like receiving mails like “Hi, can you send me an offer for translating this document” or “Can we set up a meeting on Tuesday” or “Could you please take care of that Excel calculation for customer X”.

This is stuff that can be responded to very quickly and doesn’t require much deep thinking: “Sure, it’s going to cost you $2,400, please find the quote attached”, “No, I’ll be away on Tuesday, how about Thursday 1 p.m”, or “I’m on it. Will get back to you when it’s finished.”

Even though much of this work is shallow, it nonetheless needs to be done, and someone has to do it.

However, even in a corporate environment there is sometimes work to be done that requires some thinking and uninterrupted concentration. If your boss insists that you be responsive no matter what, you’re in trouble, because this is going to be a huge stressor, trying to focus and constantly being interrupted. So I would try to get away by answering emails in 2- or 3-hour intervals, to give myself 2-3 hours of uninterrupted work, and then reply to email during an email block.

If your line of work doesn’t require too much thinking, being responsive and using your mail account as to-do list can be a way to get rid of action items quickly.

But I maintain my view that there is no universal way of how to work. This is a very wrong question to ask. The way to work depends on the work, and also on your personality. If your are managing a process, being accessible and responsive can be quite crucial, because a delayed response on your part can massively slow down the work of someone else who depends on the information he requires from you.

But then again, everyone needs to find one’s own proper balance, depending on type of work, external pressures, and personality.

A friend of mine worked for a company as a software developer where they emphasized resposiveness. When he told me about it, my first thought was: “But that means you’ll never get done anything in a meaningful way! Your code is going to be buggy and full of crap!” And he said: “That’s exactly what’s happening there every day!” I said to him, “If I were you, I’d be worrying about my skills deteriorating badly!”

He had already thought about this himself and had already tendered his resignation from that job when he told me about this.

Case in point, that essay by Paul Graham pretty much nails it, I think.

I think you can actually have it both ways. When I am working on email, I strive to respond immediately and clear the decks of my email. I make decisions, answer questions, and get things out of the way. However when I am making time for deeper work, I make time and remove myself from email entirely for some span of time. Then when I reconnect, I immediately answer what has come in and reclear the decks. So I guess I don’t find the ideas contradictory. I don’t answer email during meetings with other people, and I doubt Schmidt does either, so why would someone expect us to answer email during meetings with ourselves?

Hey Cal,

A friend of mine recommended your blog to me a few years ago, and I’ve been hooked since. I volunteer as a mentor to high school and college students through BAPS, an NGO in consultative status with the UN committed to empowering youth through spirituality and service. Much of your advice is quite relevant to them, and I cite your material frequently.

Regardless, I wanted to give you a heads up about something I saw on Professor Dan Ariely’s blog. He is a researcher in the field of behavioral economics and has been using this site to aid in cleaning up his inbox. Let me know what you think.

https://www.shortwhale.com/

Sincerely,

Rushil

Extremely apropos to this discussion is this Debug episode with Don Melton and Nitin Ganatra, former Apple technology directors: Debug Episode 47.

Melton and Ganatra discuss the constantly connected culture at Apple, the terror of going longer than three hours without checking email, answering emails at all hours of the night, and working until 2am Monday morning after late night Sunday emails from execs.

Troubling, and fascinating.

Thanks for these information. I am a young legal and political researcher and all these insight seems really powerful.

I want to share a story about deep habits in the art. I was reading a interview with Vargas Llosa, a famous writers, and I remember these blog in his phrase:

“I don’t use Twitter. I don’t use Facebook. I don’t answer the phone. I don’t open my door. I have a wonderful woman who does all that stuff for me, and that enables me to basically devote myself to what I like – which is reading and writing.”

https://jorgeramos.com/en/mario-vargas-llosa-its-ok-to-kill-a-dictator/

Amazing! Si, keep doing these posts, Cal

A bit late to the conversation, but some ramblings:

Could the key difference here be the specific type of knowledge work? Schmidt’s role at this point involves more promotion than production due to his place in the larger system of Google, from what I understand, with most of his own deep work done in the earlier days and since outsourced to his engineers. Angelou, by contrast, works in a much smaller system dependent upon the fruits of her personal deep work. Similar to the Maker vs. Manager idea from the Graham essay, maybe this situation implies a systems theory of knowledge work and/or an application of deep work to connectivity itself.