A Deep Revolution

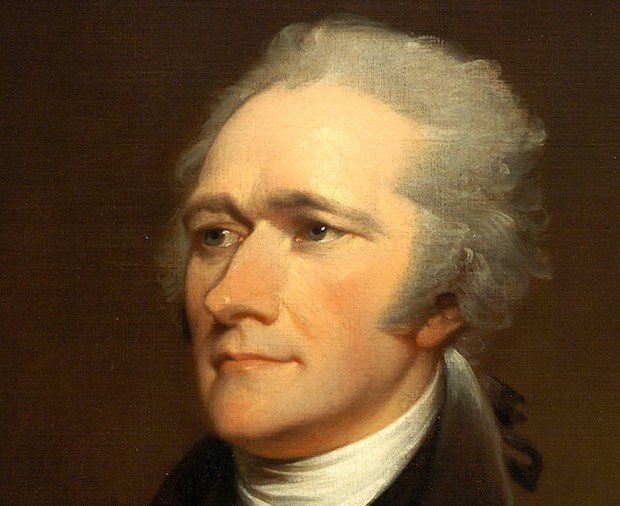

I’m a little over 300 pages into Ron Chernow’s excellent biography of Alexander Hamilton (I also highly recommend his biographies of Washington and Rockefeller).

Hamilton, of course, knew how to get things done.

“His collected papers are so stupefying in length that it is hard to believe that one man created them in fewer than five decades,” writes Chernow.

But this productivity reached an apex during the period when Hamilton, along with Madison, and to a much lesser extent, John Jay, collaborated to write and publish the Federalist Papers.

During one particularly frenzied two-month stretch, Hamilton “churned out” twenty-one of these now immortal essays.

How did he do it?

“Hamilton developed ingenious ways to wring words from himself,” Chernow explains, before excerpting the following passage from a letter written by Hamilton’s friend, William Sullivan (available online):

“[W]hen [Hamilton] had a serious object to accomplish, his practice was to reflect on it previous. And when he had gone through this labor, he retired to sleep, without regard to the hour of the night, and, having slept six or seven hours, he rose and having taken strong coffee, seated himself at his table, where he would remain six, seven, or eight hours.”

As Chernow then reveals, Hamilton’s productivity also leveraged a “fair degree of repetition” (think: depth rituals) and a method in which he would “walk the floor as he formed sentences in his head” (think: productive meditation).

Hamilton was many things. To this list, however, I think we can confidently add: master deep worker.

#####

A quick note for fellow deliberate practice fans: the father of this concept, Anders Ericsson, just published a new book on the topic called Peak. I’m excited to dive into this book, but in the meantime, I wanted to bring it to your attention.

How did the elitist, plutocratic, antidemocratic Hamilton come to be seen as a contemporary symbol of democracy? Here is an explanation:

https://takimag.com/article/alexander_hamilton_honorary_nonwhite_steve_sailer/print#axzz45EiB3pgx

It is to Hamilton’s great credit that he was “anti-democratic.” The Founders fought for and produced a Constitutional Republic (based on individual rights), not a Democracy, which most of them, particularly John Adams, knew from their study of history ultimately produced tyranny–a tyranny of “the majority.” Ask Socrates what he thought of democracy.

@Joseph Kellard

*standing ovation* .. where can I read more of your thoughts?

Cal, read both of your books and it changed my life. I have a question: you talk a lot about research problems but I can’t find any meanings for this term and how to define / formulate them? Do you have more info on this?

Jelle from The Netherlands

On the other hand, it does not quite seem like he used a fixed time schedule that Cal has supported. That is, Hamilton just sat down and spent the next seven hours on “writing”. I wonder if he used particular targets like, write 3 chapters, etc.

I think he was one of the very first person who discovered how active recall really works.

I doubt it, in ancient times, people put tremendous value on memorization, some could recite the entire Iliad and Odyssey from memory.

Speakers in ancient Rome did not have teleprompters; they delivered their speeches from memory.

Many mnemonic tricks shown today have been known for thousands of years, since the times of Ancient Greece and Rome.

Of course, one is not done when being able to recite something like a parrot, but the ability to recall what one once understood and being able to derive the results is crucial.

Cal, I found an article in NY Times that resonates with many of the concepts you advocate for (i.e. Scientific discovery takes hard hard hard work)

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/16/opinion/it-is-in-fact-rocket-science.html?_r=0

Cal, thanks for the tip on the book. I just bought it.

I am curious, have you tried to implement some of techniques that you’ve used for yourself in your classes to improve your teaching skills?

It sounds like he immersed himself in his work, which is a great way to accomplish a lot. I haven’t read your books, but I’m going to pick up your first one now.

Alexander Hamilton is an inspiration to me. A self taught master of fiance and economics; it really is incredible how complete a grasp he had of what needed to be done to put the new nation on a sound economic footing.

Washington’s ability to listen, consult and make prudent decisions was seemingly flawless. That he appointed Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury was little more than a calculated leap of faith as as was his endorsement of Hamilton’s economic plan as outlined in the “Report on Public Credit.” A lengthy proposal that Washington candidly admitted he did not fully understand. Upon becoming Secretary of the Treasury he began negotiations, largely by trans-Atlantic correspondence, to secure funding for the new government and establish public credit. He sought funding in Amsterdam at favorable rates of interest to aid in retiring the nations accumulated war debt. Despite lack of previous experience his efforts were highly successful. Amsterdam’s formidable banking syndicates came to trust Hamilton’s word enabling him to acquire new loans, refinance, or renegotiate terms upon request. Before he retired from Treasury the same Dutch bankers were offering the United States unsolicited additional funds.

His financial genius is the coolest true story about Hamilton.

Here is a quote I love that he said, “Those who stand for nothing fall for anything.”

Amazing it is truly inspirational for all of us and for next gen.