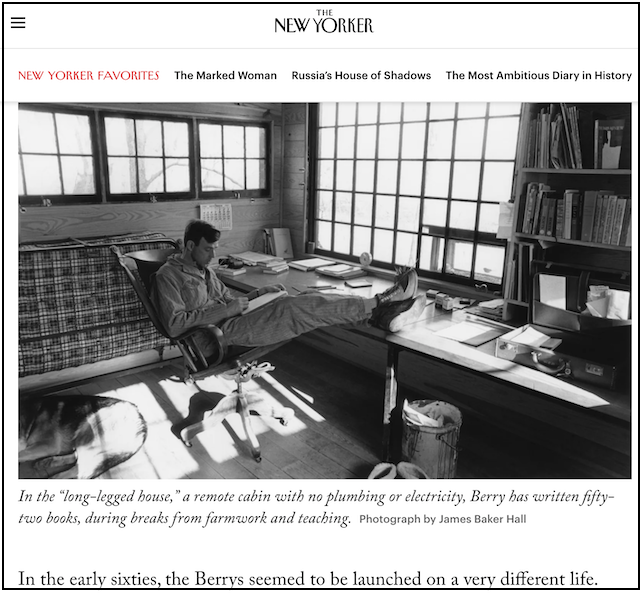

Among those who find pleasure in cataloging the habits and rituals of prodigious creatives, the poet Mary Oliver is a familiar companion. Her commitment to long walks outdoors, scribbling notes in a cloth-bound notebook, is both archetypical and approachable.

This vision of Oliver finding inspiration in her close observations of nature, made as she wanders past ponds and through forest-bound glades, matches our intuitions about the artistic process. As Oliver writes in her poem, The Summer Day:

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

We can also, if we’re being honest, imagine ourselves extracting a diluted version of this inspiration, if only we too could find the time to take our moleskin into the woods. It’s here, in other words, that we find a key piece to Oliver’s enduring appeal.