A Mixed Response

Late last year, Pew Research found that online workers identified e-mail as their most important tool, beating out both phones and the Internet by sizable margins. Almost half of the workers surveyed claimed that the technology made them “feel more productive.”

As Pew summarized: “[e-mail] continues to be the main digital artery that workers believe is important to their job.”

Around the same time this research was released, however, Sir Cary Cooper, a professor of organizational psychology, made waves at the British Psychological Society’s annual conference by identifying British workers’ “macho,” always-connected e-mail culture as a factor in the UK’s falling productivity (it now has the second-lowest productivity in the G7).

Cooper went so far as to advocate companies shutting down their e-mail servers after work hours and perhaps even banning all internal e-mail communication.

This bipolar reaction to e-mail — either it’s fundamental to success or terrible — extends beyond research circles and often characterizes popular conversations about the technology.

So what explains this oddly mixed reaction?

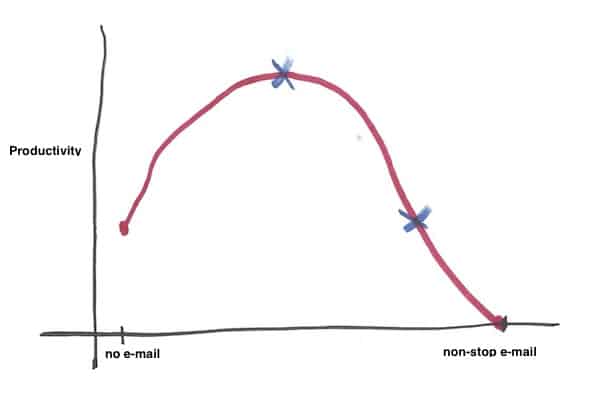

I propose that the productivity curve at the top of this post provides some answers…

The E-mail Productivity Curve

The above curve shows the rise and fall of productivity (y-axis) as e-mail use (x-axis) increases from a minimum of no e-mail to a theoretical maximum of non-stop e-mail use.