The (Lack of) Passion of the Tax Consultant

In the summer of 2008, I met John, a rising senior at an Ivy League college. He was worried about his impending graduation.

“What advice can you give to a student who wants to live more spontaneously?”, he asked. He didn’t know what he was looking for, but was clear about his “dreams to do something big.”

I gave John some advice, mainly centered around lifestyle-centric career planning, and then we went our separate ways.

That is, until two weeks ago, when John sent me a note.

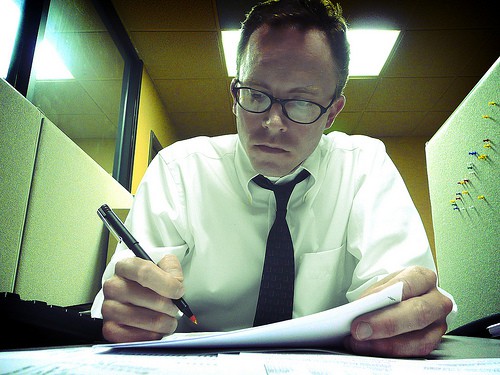

“Well, I ignored your advice at my peril,” he began. John had taken a job as a corporate tax consultant. Though he found the work to be “sometimes interesting,” the hours were long and the tasks were fiercely prescribed, making it difficult to stand out.

“Aside from not liking the lifestyle”, John complained, “I’m concerned that my work doesn’t serve a larger purpose and, in fact, hurts the most vulernable.”

Longtime Study Hacks readers are familiar with my unconventional stance on finding work you love. I don’t believe in “following your passion.” In most cases, I argue, passion for what you do follows mastery — not from matching a job to a pre-existing calling.

John’s story, however, strains this philosophy. It poses a question that I’ve been asked many times before: can I generate a passion for any job?

In other words, is there a way for John to grow to love being a corporate tax consultant?

Here was my answer: probably not.