Bad New for Strivers?

Two psychology professors, David Hambrick and Elizabeth Meinz, recently wrote a New York Times op-ed with a typically snarky title: Sorry, Strivers: Talent Matters. Many helpful readers were quick to forward me the link.

The authors of this piece start by asking a simple question: “How do people acquire high levels of skill?”

They note that research in recent decades — pioneered by Anders Ericsson, among others — has emphasized the importance of practice, and that these findings have been “enthussiastically championed” by popular writers like Malcolm Gladwell and David Brooks, perhaps due to their “meritocratic appeal.”

They then trip their intellectual trap: “This isn’t quite the story science tells. Research has shown that intellectual ability matters.”

To support this view, they cite their own research, recently summarized in a paper appearing in the journal Psychological Science, which shows that people with larger working memory capacity end up better piano players.

I’m mentioning this article because we’ve been exploring what I call the deliberate practice hypothesis — the idea that applying deliberate practice techniques to a knowledge work environment can lead to huge gains in ability and value. The question at hand is whether this New York Times piece should give us reason to pause.

I read their paper, and my conclusion is that it’s not yet time to abandon deliberate practice to start searching for your innate talent.

Here’s why…

Forget About the Final 7 Percent Until After You Maximize the First 93

What struck me about Hambrick and Meinz’s paper is that it emphasized the necessity of deliberate practice for high achievement.

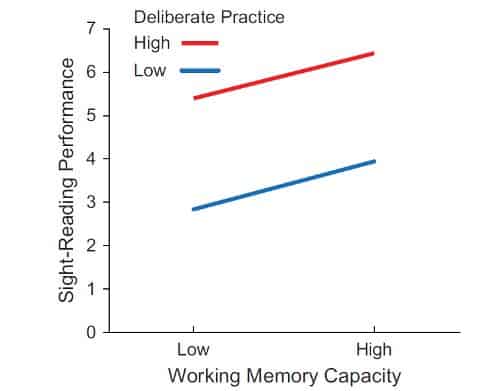

Consider, for example, the graph at the top of this post, which was pulled from their study. Both lines in the plot show how performance on a piano sight reading task improves with increases in working memory capacity, a trait that the authors argue is innate.

The red line shows this improvement for players with lots of deliberate practice and the blue line shows the improvement for players with less practice.

The key take away is that the impact of deliberate practice dominates the impact of memory capacity. Practicing more makes you over twice as good. Going from low to high working memory capacity, on the other hand, yields only a minor improvement for an already well-practiced player.

When they finished crunching the numbers, and doing the proper controls for practice quantity, the authors found that this memory capacity accounts for less than 7% of a player’s ability at this task.

From a scientific point of view, this result is important as it clearly identifies a separation between innate and acquired skill.

But from a practical perspective, it’s essentially irrelevant. The fact that these findings are so rare, and that these authors are so excited about such a small effect size, only emphasizes just how small a role innate ability seems to play in achievement.

In other words, unless you are trying to become the world’s top piano sight reader, the 7% advantage of having been born with a vast working memory capacity is not going to play a major role in your achievement.

Now let’s return to the setting that concerns us here at Study Hacks: knowledge work. The deliberate practice hypothesis assumes that almost no one in this setting is working in a way that approximates deliberate practice. In the context of the Hambrick and Meinz study, most of your coworkers are therefore on the blue line from the graph above.

This, of course, only reinforces the idea that embracing deliberate practice can have a profound effect on your ability in this work setting, as this embrace will vault you to the red line. From this lofty perch, minor differences in innate talent won’t matter. Your overwhelming value has already been definitively established.

#####

This post is part of my series on the deliberate practice hypothesis, which claims that applying the principles of deliberate practice to the world of knowledge work is a key strategy for building a remarkable working life.

Previous posts:

- Perfectionism as Practice: Steve Jobs and the Art of Getting Good

- Complicate the Formula: John McPhee’s Deliberate Practice Strategy

- If You’re Busy, You’re Doing Something Wrong: The Surprisingly Relaxed Lives of Elite Achievers

(Figure from Psychological Science)

I think the story gets even better for deliberate practice. One implicit assumption made in the ‘talent’ argument is that working memory is a fixed, innate ability. However, there is evidence emerging that this might not be the case. For instance, a recent controlled trial by Jeaggi et. al. (https://www.gwern.net/docs/jaeggi2010.pdf) found that an n-back training exercise can improve working memory capacity.

Furthermore, anecdotal evidence from those who actively train their memories is that it leads to general improvements in fluid intelligence (e.g., I’ve recently seen the claim in this book https://goo.gl/KcWbp). Of course, the argument could be made that those selling memory improvement books have a certain barrow to push! Yet, competitors at memory championship events frequently remember *hundreds* of random numbers within an hour (random number memory was the working memory test employed by the researchers in the NYT op-ed). And even rudimentary chunking techniques have been shown to extend people’s ability to hold more than the standard 7 (plus or minus 2) items in working memory.

So, deliberate practice of techiques targeted at improving working memory would likely move people on the left hand side of the graph above over toward the right.

I wonder if “working memory capacity” is something one can improve as well?

The authors knew about the claims/studies showing a connection between working memory capacity and practice. They claimed they controlled for that (by looking at people who had spent the same amount of time doing things that might help memory).

But your points ring true to me as well. This seems to be a major argument of Ericsson: be careful about labeling something as innate, it might be trained in ways you didn’t realize.

Take muscle-building. For the average gym-goer, the protein powders, supplements etc are a 3% edge enhancement effect that can’t replace the 97% consistent deliberate technique and effort. Genetic talent counts too but the work is very necessary.

This article reminds of the debate about marathon runners ruining their feet with all this running. When they tested the feet of marathon runners, they found very few problems with the feet. So they started to believe that running would help bad feet. Yet another Doctor theorize that that people with bad feet wouldn’t run marathon so all marathon runners were people with superior feet.

So I figure people who use their memory would be one that can use it. The ones who won’t, don’t try.

You actually can improve working memory capacity using a series of “N-back” brain exercises. This summer, I used one software and improved my working memory capacity 60% with 20 days of training for 30 mins/day.

Seems like a better title for the article would be: Sorry, Strivers, Talent Matters (A Tiny Bit).

Of course, it wouldn’t have gotten into the NYT by telling the whole truth, so it’s a good thing (for the authors, not their readers) that they didn’t.

I’ve read the article, but not the paper, and I think that there’s an important distinction that is missed.

The authors of the NYT article seem to equate working memory directly with talent, which seems more than a little artificial. In my personal experiences with those concerned with ‘talent’, it seems that the term is really just used to cover the amorphous element of the factors that provide a person with a particular skill set.

For example, if we were to take two young chess players, who had practiced for exactly the same amount of time, had the same measurable intelligence, etc., if one of the players demonstrates a higher level of proficiency then people are quick to put that down to ‘talent’. In reality, I believe that most or all of these differences are down to factors that are just as real, but harder to quantify. Both players may have the same number of hours of deliberate practice, but there is no way of knowing if one player’s practice had been more ‘deliberate’ or efficient than the other’s. Likewise, one player may find that he has been distracted during the games used for measuring their abilities, while the other wasn’t, or perhaps one player had seen a movie involving two people playng chess, and this gave him an idea that he used during the games.

Does this mean the the supposedly talented chess player instead has a talent for learning, not becoming distracted, or creating connections? Unlikely, as there will no doubt be similar factors to these abilitites as well, and so we can keep chasing the notion of ‘talent’ forever. Because of this, I think the primary use for the idea of ‘talent’ is that it simply stands in for all of these factors in a simple-to-understand way, but is by no means innate or unique (the argument for my idea here can get very complex, so I’ll not go into any more detail here).

The other element of ‘talent’, as understood by the general public, is that having talent necessarily means being discovered at some point. To use another chess example, the young Norwegian chess player Magnus Carlsen, who became a Grandmaster at the age of 13 and the world’s number one at the age of 20, must have been discovered for his abilities at some early stage, so what hope is there for the rest of us? Well, imagine if Carlsen has been born in some remote location, where he did not even get to see a chess board until his 20s. If you subscribe to the notion of innate talent, then he would have the same amount of potential to become a great chess player. Simply put not being a discovered talent does not mean you do not have enormous amounts of talent for something.

If you put these two ideas together, you come up with the following dilemma: If talent does not exist in a pure form, then all you need to become great is a lot of practice, and if it does exist, then it is quite possible you have some anyway.

Cal, your links aren’t working. I tried the one about the Chess GMs and the John McPhee one and both return 404s.

Isaaha Crowell, the underachieving yet highly recruited Tailback for our Georgia football team would love this article. Better known for his “dogging it” rather than working through the pain…sounds like this study was done by the “occupiers”.

Although, of course, assuming that there is a talent factor of 7% or so that might pan out to be extremely important in the end. Especially in extremely competitive fields.

Let’s take the example of tennis. If the few percent of talent would make the difference between someone who becomes a top-1000 tennis player (still a great player, but not exactly a good career) and a top-10 tennis player, you might want to take that into account when you decide on career paths as a teenager…Of course, this matters less in less competitive fields…

Anyway, I would be really interested in your views on how to apply deliberate practice to knowledge skill acquisition. Let’s say become a good writer, as an example. Maybe an idea for a future post?

“Sorry, Strivers: Talent Matters” Okay… so what the hell is talent, if not something learned by… practice. So, .. ok, show me a 9 year old Kobe Bryant, and remind me again what part of his ‘talent’ was inherited from his parents genetically? What percentage would that be? 5%? 10%? I mean, really? What we even talking about at this point? DNA? His height? Agility?

That’s not talent! I’m not really sure what the heck ‘talent’ is if it’s not something you can learn by rigorous practice.

To bestow upon someone the talented label harkens back to the 17th century (or so) when people actually meant God had bestowed talents upon someone at birth. Ugh!! Drivel. Absolute jibberish.

Hint: For anyone who didn’t pick up on it, no I don’t think Kobe was an excellent basketball player at 9 years old, though he certainly was playing alot in those days. It would take another 10 years or so, before his talent reached the level of NBA greatness, and even then, it would take ANOTHER 5 years before he was hitting big shots in big games. Whatever was innate or inherent about his abilities, they certainly took their sweet ass time ‘revealing’ themselves to the world.

Or maybe Kobe just busted his ass in practice. I’m putting my money on the latter.

Cal, what do you think about the study by the Vanderbilt University researchers David Lubinski and Camilla Benbow that was mentioned in the article?

Fantastic series Cal, keep them coming!

I suspect this is absolutely correct.

This is also probably correct. Also keep in mind that his dad played pro ball, so he had been exposed to exactly what it requires, what matters, what doesn’t, etc., which probably gave huge gains in structuring his acquisition of skill.

They were concerned with pushing back against the threshold hypothesis. The work didn’t really make claims about the importance of practice. (i.e., the test results they used in their experiments could very well be the outcome of deliberate practice).

I agree with Dave that treating working memory as if it’s the same thing as talent is off-target. And on the point that talent is most often a catch-all term for unseen influences.

My education is in architecture and visual design. In that environment, the strongest students were certainly engaging in deliberate practice. Beyond that, however, there was another common thread which, to me, is the closest thing I can name to talent: enjoyment.

Designers who enjoy their work are more confident, driven, and curious. Lesser students may put in similar quantities and types of practice, but the students who truly enjoy the work consistently turn out superior projects.

In my mind, your capacity to enjoy your work effects the same results talent would. But I suppose if we insist talent is set at birth, unchangeable, then my definition is still off. Enjoyment can certainly be increased.

There are so many other factors besides talent anyway. Furthermore we may not necessarily know what all these factors are. It wouldn’t make sense for a person to wait and see if he has everything before he starts to embark on something.

Interestingly, deliberate practice itself can help with working memory. The more familiar one is with a certain subject or field, the easier it is to remember things which are related to it. You might like to check out “How People Learn” by the National Research Council. It may be a bit dated but it mentions many fascinating findings.

I remember that in one study a group of chess players and a group of people who didn’t know how to play chess were given a chess board with pieces to remember. The chess players were able to recollect the positions of the pieces better. Another study (or was it the same one?) placed the pieces in random positions rather than giving the subjects a board where the pieces were in positions that were a result of a gameplay. Interestingly, the memory of the chess players were poorer than when the pieces were in positions resulting from a gameplay.

There was another study on memory with a grimer conclusion. A college student was tested on his memory of strings of numbers. Thereafter he went through practice for some time and he managed to increase the number of digits recalled quite significantly. He was then tested on a string of alphabets. Guess what? The number of alphabets recalled was similar to the number of digits recalled at the very start of the study. It shows that training of memory in one area may not transfer to another. However this is not to say that if a person was taught general memory techniques such as chunking or the peg system it would not benefit him. These techniques can be applied to many different situations. However if a person is already using these techniques or are not using them, then it is likely that his memory would be better in something that he had practised a lot in.

I’d agree that things like working memory are not innate and can be improved through practice. (If anyone would like to test this out, cognitivefun.net is a great place to start.)

Sorry, here’s the proper link.

Not sure about the research results. There have been papers which conclude that even working memory can be increased over time with deliberate practice. Remember the ‘n back’ game. Even if the results apply to extreme cases, the assumption it rests on is not valid.

Cal,

In my opinion, talent is the only thing that separates the very good from the very best, something I picked up by reading your article on the Superstar Effect. Deliberate practice as you say, will get you a very, very long way.

Like Jordan, I also thought of your Superstar Effect article, too.

I think practice is the thing that sets apart the good from the very good. But we all have ingrained “talents” or personality or things we’re naturally better at/come better to us. I think when we discover those things, combine them with practice, thats when we can become the best, like the Superstar Effect.

(Although I should point out that article was both very helpful and had more of a subjective, create your own project to kick ass at as opposed to a “do this and become #1 in basketball” mindset)

Sport and music are useful for studies because individuals compete directly for the same goals so comparison is easy. I don’t think that perfect competition like this exists in most knowledge work because the goals and constraints aren’t as well defined. In knowledge work competition with a more ‘talented’ party easily is avoided by focusing on points of difference instead of commonality.

Talent abundance or lack there of cannot be an excuse not to practice.

Hi Carl,

Thanks for this article. Today, I have written a post entitled: “Do recent publications prove Anders Ericsson and colleages wrong about the importance of deliberate practice? No.” It mentions your argument and a few additional arguments. You can fiind it here: https://bit.ly/sK5mgO.

Hope you’ll like it.

Here’s a video today from the Wall Street Journal – “Why A Stimulating Job Can Improve Your IQ.”

Over the course of four years the IQ scores of students who took on complex work moved in some cases from the 68th to the 97th percentiles.

Come on people. Stop linking genius with piano playing like the report. We might as well call most women geniuses since they’re so good at secretary work. Have you seen them at work. Nearly flawless.

Piano is nothing more than a device. The reason it is arranged in black and white was to save space. It is nothing more than using a cash register.

One could hypothetically write a software that allow the computer keyboard to play musical notes. Then would you say person playing music on a piano is better than and person playing music on a computer’s keyboard? Absolutely not.

Heck, I could go further and say one could write a web application that if you click on a notes on the screen it’ll place the note on the scale. Afterwards, you could push the play button and your music script is played to you.

Now, think of that. Who is better? The person creating the music script or the playing back a music script?

This is the kind of stupidity that causes asian parents to have their kids play musical instruments. They think Mozart, etc.. and think piano equal genius.

Piano is no different to any other task, in that simply doing it is not hard, nor genius.However it all boils down to how well you can do it, and to reach the highest levels does indeed require nothing short of genius.It is extremely rare that any person can be trained into even the top ten percentile in most musical endeavours, even after tens of thousands hours deliberate practice, 90% of people will be nowhere near what would be considered “expert” level. To give an idea, even a minute sub skill, such as a thumb tuck, might consume hundreds of hours to get to an acceptable level. Scales might consume 2000 hours to perform at the correct standard.Very few people will ever reach a virtuoso standard, even amongst highly dedicated individuals, most will fail.

Cal,

This discussion is terrific. But I read a blog post today that fits brilliantly into one of your other categories, “Relaxed Superstar.” It’s a law professor’s report on how he structures his prolific writing schedule and still gets to quit at 5pm and take week-ends off.

Oops. Here’s the URL. https://prawfsblawg.blogs.com/prawfsblawg/2011/12/how-i-write.html

@ Mark “We might as well call most women geniuses since they’re so good at secretary work.” Nice.

By that logic, you’re a genius too, since you’re so good at being a d-bag.

@Gerbera, it is how you interpret what I said that makes me sound like a d-bag.

I was comparing the secretary’s nearly flawless typing to a pianist hitting the correct keys. I find both amazing. But I can see those devices are nothing more than mechanical devices. Somehow, the beauty of a device = smarter user? That makes no sense.

Researchers that allows their feeling toward a subject matter adulterate the result of their experiments. The nostalgic feelings are that music is somehow linked to the musical geniuses such as Mozart and Bach. Then people jump to the conclusion that playing a musical instrument = smarter. Sure, you must know what you’re doing (need a brain) if you’re playing a musical instrument. Same is true if you’re working a cash register or any other devices.

Forgive me if what I said sound like an insult to women. It was more of a praise even though it didn’t come out like what I intended. I was furious at the researcher who went from A to C with magic.

@Mark: Ah but I suppose the speed and rhythm one presses the keys plays a more important part in piano.. but I get your point..

Oddly, the last two links 404 if you are reading from the RSS feed, as they are missing the /blog portion of the URL.

There is a lot of really good discussion on this topic, and a lot of hard evidence that is directly related. After reading everything here, I wanted to add an additional perspective that has not been put in overtly yet.

“Talent” as unfortunately subjective and unquantifiable as it is, has a point. I’m reminded of Tim Ferriss when he talked about trying to push through and analyze/practice through certain kinds of dancing and sport, only to find it enormously difficult compared to other things, and instead of looking at the task itself as impossible (obviously not when other people can excel at it), he looked at his own body and his own genetic makleup. On reflection, he realized that his body was built to do certain things really well, and was not optimized for certain other things, then he started playing to those strengths.

I think there are a lot of factors that we are only now starting to understand (dna may be our parts, but it is not a limit and how deeply ingrained it can be for kids to be exposed to patterns of learning and growth as two examples), but there is definitely enough call for us to pause during our journeys of life-long learning and really ask what’s right /for us/.

People with certain advantages (aka one meaning of a talent) will gravitate more towards the things they excel at, meaning that quantifying a sport or activity based on the people at the top is very hazardous when it comes to explaining to “everyone” how it works.

In short; innate ability and differences in the nature or nurture of individuals may not mean much in terms of excelling, but are certainly worth listening to in order to lead a remarkable life (and, in my opinion, the best way to grow as a planet – we need all different kinds of people, and it would be remarkable in itself to witness every one of those people as passionate. “Be the best you”).

also, just because I think this might help a smaller debate:

@Mark: It’s not the flawless execution that makes a piano player or any musician known as a genius, it’s how they subtly interpret the notation and infuse it with emotion through timing of the space between notes, how they choose to hit each key; with how much speed and pressure, how long they hold it down, and many other ways they can affect the tone of the strings as well as the music itself.

There are instruments built on one string that can be as emotionally expressive as any other – I don’t think a keyboard with a single key would even come close (though in certain extreme cases of artistic perseverance, there might be an argument to be made – people are capable of stunning things)

Cal, you misunderstood the deliberate practice model.

Ericsson didn’t say “deliberate practice is important”. They said it’s SUFFICIENT for world class performance:

Actually Ericsson did very definitively say that talent doesn’t matter at all:

Our theoretical framework can also provide a sufficient account of the major facts about the nature and scarcity of exceptional performance. Our account does not depend on scarcity of innate ability (talent)…. We attribute the dramatic differences in performance between experts and amateurs–novices to similarly large differences in the recorded amounts of deliberate practice (p. 392, emphasis added).

I communicated with ericsson not long before his passing.To cut a long story short, I questioned him as to why a person, such as myself could engage in all correct practice tecniques and regimes, being certain to only employ deliberate practice, yet after 9000 hours of training remain a very poor performer. By the end of the discussion, I had more or less convinced him that a memory disorder i suffer from was the core reason for my failure, and it was his suggestion that if the memory disorder cannot be treated (it can’t), then i should re-evaluate my aspirations. What struck me was that this was at odds with his “official” stance, that basic cognitive abilities were not critical for expert performance. Given that all learning processes are entirely underpinned by memory function, one must question Anders Ericsson original assertions regarding the role of intelligence on skill aquisition.

I really think there are serious misrepresentations of fact which Ericsson presented in his papers. It is blatantly obvious that deliberate practice is a VERY unreliable predictor of success.For example, there are multiple examples of people from all domains, who achieved world champion status with far fewer than 10,000 hours of practice. Why Ericsson never aknowledged this?

A lot to be said about all of this.Firstly, regarding intellect, most studies which purport to show IQ gains as a result of interventions have methodological flaws.To date it remains unproven that IQ score, particularly in adults can be improved by any means at all. When the N back trial was re-run, the original gains attributed to it could not be replicated. What can be said is that inheriting the genes for intellect (numerous of them have been identified) is by far the best way to become smart, as it requires no time or effort for a potentially very large advantage, whereas training requires enormous investment of time/effort for questionable gains.

There is no doubt talent overshadows deliberate practice as a driver of success.There are children of less than 10 years age who can effortlessly outperform adults with 30 years of professional tuition, by the best known methods and techniques.Most people, even with very good tuition, could only gain a basic grasp of piano within 10 years of training, a level not even remotely close to mastery or even a professional standard. The rate at which different individuals learn varies enormously, and the mode of practice/training certainly does not account for this.The difference is due to a multitude of factors, most out of control of the individual.