Project Problems

Earlier today I answered an e-mail from an undergraduate at a well-known college.

She was studying neuroscience. A true believer in the Study Hacks student canon, she had pared down her commitments so she could focus her attention on her major and a related research position.

But then came the second paragraph: “I have a new project that I want to put together,” she said. “Something about the neuropathology of abnormal psychology.”

She admitted that she was having trouble with this ambition because no one at her school did behavioral neuroscience research.

“But I really want to get involved in that area,” she emphasized. “How do I find someone to work with me? I’m stuck.”

I told her to abandon the idea.

The Necessity of Depth

I’m telling this story because my advice emphasizes a deeper principle that I find myself frequently teaching the students I work with: successful projects are born out of depth.

When you dedicate the bulk of your attention to a small number of things, working persistently to become so good they can’t ignore you, this builds depth. When you have reached sufficient depth, you begin to encounter possibilities for impressive, exciting projects. (High school students should see my most recent book for advice on making this happen at a young age.)

By contrast, when you come up with a project from scratch, in a field where you have little standing, you’re essentially filling in an aspirational Mad Libs — a worthless combination of vague directions and outcomes.

For example…

- Declaring out of the blue, “I want to help [group X] gain more [thing they have limited access to],” is meaningless, equivalent to saying “I want to make the world better!” or “rainbows are nice!”

- On the other hand, going to work for an organization that actually helps that group gain that resource, and learning the intricacies of their world, paying your dues, then eventually introducing some innovations from within: that’s the foundation for then going on to launch a fantastic project on your own.

Returning to our sample student from above, I told her to ignore her Mad Libs project and instead double down her efforts on the research she was already conducting. If she could become so good she couldn’t be ignored in that well-established context, fantastic opportunities would come her way — opportunities that would be every bit as rich as her fantasy project.

Beyond Thinking Differently

My wording in this post is harsh, but this is a purposeful strategy.

In my experience, students have been taught to place way too much importance on having the courage to follow their passions and change the world, and not nearly enough importance on having the persistence to first build the needed ability to both find concrete projects that matter and accomplish them.

“Think different,” they’re told, without also being told about the decades it took Steve Jobs to build the experience — often through failure — needed to transform Apple into the innovative company it became in the last two decades.

With this in mind, I use harshness to snap my student readers into a new way of thinking. I want these students to be wildly successful (which is why I’ve written three books on the subject and personally correspond with over a thousand of them per year.)

This particular piece of tough love happens to be one of the most important tactics in my arsenal for helping them achieve this goal.

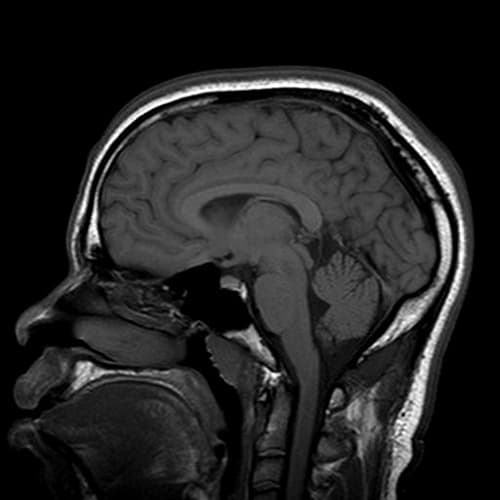

(Photo by knitguy)

Great advice.

You should tag this as Patterns for Success in the Working World.

Great point Cal,

The temptation to start a new project is always on the back of people’s minds when all they really need to do is to focus on the current project and make it happen.

I know you have more experience than me and are probably right. But isn’t it a bit too much that you would just ask your student to just give up on an idea of her’s just cause there is a high risk that she will fail. Where would Apple be if somebody had convinced Jobs otherwise.

Personally, I see room for both types of people, and those in the middle. We need some people to go deep, work hard, and push the boundries of our understanding of reality. But we also need others to learn to play with the universe, to inspire us to have fun, and to not take life too seriously. Most of us fall somewhere in the middle, of course.

So true! In high school, I had this elaborate plan in mind to make a change in the world, but now I have put that plan on the back burner. After thinking about it, though, I realized some of the problems with this plan that I would have disregarded while in that “honeymoon” phase.

I think it’s really easy for some of us to elaborately plan out our futures. While there’s nothing wrong with that, I also think it’s important to remain open-minded to the unexpected.

I personally have trouble with the open-mindedness part, and I know I’m not alone!

While there is success to be found for those who specialize & create depth, there is also a place for people to be generalists & tinkerers. Many of the innovations that led to explosive growth of British industrialism during their industrial revolution are the result of tinkering by generalists with a slight amount of depth to their knowledge. Surface knowledge is pointless, but it is useful to go outside your boundaries to expand your options for solutions sometimes. Most people aren’t wired this way & use the “I have this great idea” as a way to procrastinate or indulge a feeling that the grass is greener elsewhere.

To Nishant and Matt: I think you’re right, we need a balance of stratospheric ambitions, but also hard work and steady development. But I don’t think Cal’s argument is either/or.

I don’t think he was discouraging the student from pursuing the project because her probability of failure is high. Rather, he’s pointing out her chance to change the world lies in the field where she has the most support and experience. Changing the world takes much more than one good idea. It takes a network of knowledge and resources she likely only has in her current field of study (doesn’t mean it won’t change later).

Jobs’ success was at least partly due to his ability to purge shallow ideas from his thinking — to recognize when a shiny new idea was going to leverage his experience, or require a change in direction that would result in less success and impact.

It’s certainly a positive thing to have an abundance of ideas. Better, is to have the ability to tell which ones to follow. The ones that change the world are often found in our own back yard.

I think you’ve done this student a grave disservice. If she has a specific interest that is not well supported at her current institution, I would encourage her to look into transferring.

Digging deep is important, but digging deep in a subject that fascinates you is truly an experience not to be missed.

There are real-world considerations, of course. It’s possible that by continuing her current research for another semester, she could produce a sufficiently impressive result that transferring would be easier, or she would be more likely to get into a more prestigious school. But I think you also have to weigh how likely it is that she could produce such a result in that amount of time.

There’s also the question of how interested she is in behavioral neuroscience vs. in her current resesrch. If everything she reads in behavioral neuroscience fascinates her, or if her current research is particularly uninteresting, that would supply stronger motivation to seek a transfer.

The problem with waiting to do what you love is that years turn into decades a lot faster than you expect… and you could still be waiting. Carpe diem!

This is an important point: I’m not tell her to give up on an idea because there’s a high risk she’ll fail, I’m telling her to give up on it because it’s not really an idea, it’s just a vague combination of high-level goals. Real results come from well-designed concrete projects. These require depth. When you’re coming up with project ideas before you have depth, you’re not really coming up with useful plans of actions.

I again feel it important to clarify. I am not arguing against creativity or boldness. I am arguing that creativity and boldness first requires depth. That is, given two people with depth on a topic, some might go a safe route and incrementally advance knowledge, while others might go a bold route and try big, sweeping changes. In both cases, depth is a pre-requisite.

Something which requires depth in the field. My ideas for consumer electronics, for example, are worthless. Not because I’m not bold, but because, unlike Jobs, I don’t have years of experience in the field.

Nonsense. I don’t believe there is much value in a “specific interest” if it’s not based on any real consistent effort on the topic. Real passion almost always comes out of the quest for mastery. The random thought that some topic she heard about seems cool, especially at her age, is usually just a symptom of the type of “grass is always greener” thinking that we eventually lose with experience in the world.

Why assume that the new project is the mad libs project that she won’t stick with long enough to build depth in? I feel like I would have given the opposite advice: if her existing research position isn’t in the topic she wants to pursue, she ought to ditch that and build depth in the new area that she cares about.

After 5 years of building depth in an area that was originally somewhat satisfying but grew less satisfying each year, I’m skeptical of the idea that it’s important to go deep along a particular path just because that’s the path you happened to choose first. It’s all too easy to end up with a PhD in a field that isn’t a good fit for you simply because one is too afraid to risk wasting time on less related pursuits.

No, it’s not a linear process, it’s a spiral. Fleeting interest leads to casual pursuit of an initial taste, which can ignite a slightly more intense interest which leads to slightly deeper pursuit of ability, and so on. It takes many trips around the cycle to reach mastery.

You haven’t told us what her interest is based on. For all I know, she has done substantial reading in the area. Maybe you can tell from her communication with you that her interest in behavioral neuroscience is newly conceived and not yet deeply rooted. In that case, I would encourage her to do some reading on the side. Yes, it could be a bit of a distraction, but better to get some idea how interested she really is in than to leave it unexplored.

A transfer is a nontrivial undertaking. She would have to go through a whole application and admission process again. Then there’s starting over in a new environment, having to make new friends, etc. I think contemplating that, and maybe even taking a few steps in that direction, would force her to confront the critical question of just how badly she wants to pursue this new field.

And in the end, she is really the only one who can answer that question. Not I, and not you.

A propos of needing depth for successful projects, long before Mr. Cain suspended his campaign for the presidency, David Brooks repeatedly said on the “Newshour” that people who are serious candidates have been preparing themselves for years, but Cain lacked the preparation.

hi Cal!

i have been reading Your blog since quite a long time and want to use this first comment to express my appreciation for the great content You regularly provide us with!

as Your discussion with Scott clarifies, additional information is required for understanding the context of the question and respectively of Your advise.

the fact this girl is an undergraduate student, however supports the notion her knowledge in neuroscience, though possible substantial reading, could not be that deep. especially, if substantial part of that reading has been done to provide her with basic understanding of the nervous system itself.

which, correct me if i am wrong, is the main object of both neuroscience and neuropathology.

i strongly agree with Your point:

On the other hand, concurring with Scott’s advice, to do some reading about the topic, may enable her to find synergies between both fields.

it would allow her to correlate her interest with her current project, not having to transfer schools and provide her with enough knowledge about neuropathology. which than should help her clarify, which field to choose for her graduate studies.

This is really interesting (I’m the person who initially emailed Cal – thanks for the response by the way)!

I’ve been interested in behavioral neuroscience for quite some time. I’m majoring in behavioral neuroscience specifically, and all of the research areas that I’ve found interesting have had to do with behavior in some way. I’m most excited by strange behavior, that which we consider abnormal. I *have* read a number of books on it, and while they haven’t all been technical, they cover a range of abnormal behavior. It’s not that I want to email someone and ask them to support my project, but I’d like to get involved in that field so that I might eventually end up doing something in that area. It’s difficult to get depth without a mentor in that area of study, especially since I’m interested in research. I’m well aware that I don’t yet have the depth to create a concrete project, but I know that I am headed in the direction of doing one, especially because it’s something that I’d like to study in graduate school. If I’m headed to grad school with an interest in abnormal behavior, shouldn’t I try to get involved in research that’s at least related?

It seems to me that you are saying here that being great is enough (big ambition). Somehow, I don’t think it is…

I’m middle of the road on Study Hacks, but I just can’t get on board with this particular implementation. I understand the point that passion should not be the deciding factor when making career decisions. But it goes to far to simply ignore interests/passions, even if that interest is only in its infancy. This student’s initial interest may be what is needed to carry her through the more difficult times.

Perhaps we don’t actually disagree here though… can we agree that there is some minimal level of interest in a field (and more than just a small amount) that is required in order to feel satisfied with a career in that field?

I have a significant amount of time and energy invested in my expertise, and seem to be headed towards good things. The work does little for me, however, other than offering me the opportunity to meet other bright people. I’m told that I receive the best and most interesting work available (at my employer at least) due to the excellent work that I have done. And yet I feel as if spending my time on these things is an utter waste, and that my personality is being slowly ground to dust. From reading Stuck Hacks, I think, perhaps, that if I continue to excel at this job, I can one day turn it into the job I want (the only thing I can think of in this field is to continue this type of work except not really needing to do it too often). You may not believe this by reading this post, but I’m generally a positive person. I can’t help but think that starting earlier on something that was more interested to me would have been a better route.

@Catie:

Thanks for writing into the comments. I’ll clarify my thinking here with some more details…

The standard school of thought regarding academic career development is that as an undergraduate, you’re basically stuck with whatever undergraduate research opportunities are available in your general field.

As you noticed, your choices, as is often the case for undergraduate research, are really limited. That’s normal. My undergraduate research at Dartmouth, for example, was completely different than what I did as a graduate student at MIT and do now as a professor.

Your goal, then, is to prove that you are capable of graduate level research (and to start learning the general body of knowledge of the field). The research you have access to now will force you to tackle real research problems and build real research skills, etc.

These general skills get you into graduate school. Typically, it’s the choice of your graduate school advisor that is the first time you start to direct your work toward a specialty.

As you gain more experience under as a graduate student, you start to gain a more nuanced view of the field, and it’s here that you specialize even more — perhaps even switching advisors — in preparation for writing your dissertation.

In other words, it’s generally thought that your undergraduate years are too early to be specializing: you don’t yet know enough about what’s happening at the cutting edge of the field right now, what’s hot, what’s not, what resources will you have available (which will depend on where you go to graduate school and what advisors are looking for students, etc.).

A different way of summarizing my advice then is to focus in the short term on the concrete projects that come out of your existing research setup. But keep your long term ambition to find an exciting specialty alive.

@Ray:

I have nothing against interests or passions. I just don’t think the are the miracle cure most people thing they are. There is this belief that they represent something innate and by following them you will definitely become happy and love what you do. In my experience, they are more fleeting and often more superficial than you might imagine. They certainly don’t automatically confer fulfillment, that will require building career capital (which you are doing) and then investing that capital strategically to shape a career *you* enjoy (which it sounds like you are not yet doing).

I always love your advice but I’m not sure about your argument it this post. In order to reach depth in an area, don’t you first have to have that passion to start something new and learn about it? Just because she is studying neuroscience does that mean she should stick with it her entire life/or even just during her undergrad years, because she chose that research area when she was still pretty young? And neuropathology is not completely unrelated anyway. She still has a lot of time to get good and reach depth and she can surely transfer any skills she gained from her neuroscience research.

You are telling people to “succeed”, but you are also telling them to give up their dreams.

That depends on “what’s your value?”

I won’t spend a lifetime to do something I am “good at” or really have great chance to “succeed”, but will be happy if I can do what I want to do. Thus I can’t agree with you.

@Cal:

Thank you for clarifying! That is quite helpful. The problem was that I was under the impression that what I was researching was going to be crucial later on. If not, then the problem is solved right there, as I really enjoy working in the lab that I work in.

Thanks for your thoughts!

I’m with Cal 100% here, especially because I was in roughly the same position as Catie before (except it was cognitive neuroscience instead).

This post makes me sad because I wish someone had given me this exact advice when I desperately needed it. I wasted many good years of my life trying to be a dilettante in a field where my background was, in retrospect, shallow at best.

(Yes, in retrospect, because I had completely misestimated how much I knew back then.)

Cal is also absolutely right about focusing in depth though not necessarily in your prospective graduate area. I did eventually find a graduate program that was just right for me because I was able to leverage the depth I had inadvertently built in a different field. Caveat: in my case, the methodologies I’d learned were transferable across both fields, but it may not be the same with Catie.

@Boe:

Would you be willing to share more of your stories? Perhaps if you have already done so via a blog post, would you be willing to link to it?

I found this post to be quite provoking and incredibly relevant but am definitely still very interested to learn and discuss these ideas further.

I wish someone had told me this in the beginning. I definitely wasted at least 3 of my undergrad years chasing projects that I had hoped would give me an interest-fueled depth that I felt I was lacking in classes.

A story that I think relates to this. A good friend of mine majored in philosophy in college, with a focus on philosophy of the mind. By late in his junior year, this interest in philosophy of the mind had led him to an interest in neuroscience. He decided he wanted to pursue this interest as his research focus. However, it was too late in his college career to switch his major. What his advisor recommended was that he supplement his final philosophy classes with research experience in a psychology lab so that he could get a research assistant position after graduating–the prerequisite for such a position being basic knowledge of the brain and simple scientific research experience. He followed this advice and gained a couple semesters of experience before graduating. That experience helped him land a research assistantship at a university-affiliated neuroscience research lab. He spent two years gaining specific research experience there and then applied to PhD programs. He is now in his third year of PhD work at the ideal university for his focus.

What should be noted on top of this is that his research-idea changed pretty drastically over these years. Not because his interest changed, necessarily, but that as he gained more knowledge and experience, he realized how naive and ill-informed his original idea was. Regardless of that, the point is that the undergraduate years are a time to gain experiences, not to set oneself the goal of creating new scholarship. Even though the precise option isn’t available for Catie, it sounds like she has ample opportunity to receive knowledge, training, and experience that will set her up to make similar upward moves that my friend made.

@ Cal: Your main objection to Catie’s idea is that she might not have adequate depth during her undergrad semester to come up with a “perspective changing” project. But, let’s say she has put in so much effort that she instinctively understands her subject. How does she know if it is the “right” thing for her to switch? Essentially, are there any measures (doesn’t matter how vague the measure sounds) by which she can self-evaluate if she has adequate depth? Even to find a mentor to help with an evaluation requires time. So, self-evaluation is a good point to start. If she does not know what she should be knowing, how should she self-evaluate if she knows enough?

Great post Cal. I’m one of those dilettantes that really do have trouble focusing on one particular thing long enough to really make an impact, and for years I’ve prided myself on my wide variety of interests. I’m only starting to see the consequences of that recently.

Right now I’ve been going into the field of science education, and though I’m already dreaming about totally unrelated fields, I’m forcing myself to limit the power these urges have over me and will pursue my graduate degree in science education as well.

I’m not experienced enough yet to know for sure, but I feel that if you show ‘depth’ in your field, even if you decide to jump into another field down the road, you’ll be taken a lot more seriously because you’ve proven your ability to commit to something and produce something contributory. This would be opposed to someone who is a Jack-of-all-Trades who has very shallow background in a lot of fields as they would seem very lackadaisical.

After I establish myself well in science education, I will use that as a platform to explore the other sciences that catch my interest in the future. Of course, being a teacher, my summers are free to research whatever I want wherever I want! =]

Cal,

Just about everything you write helps me to make cut throat decisions. It’s the advice that I pray for but that I can’t seem to find anywhere else. It’s clear and concrete and I can’t get enough.

I’m actually going to promote your idea of being ruthless with your schedule on my next blog post. It’s a philosophy that has absolutely changed my life. I used to be someone who constantly took on more and more tasks, and the trick of defining your hours and then cutting what doesn’t fit is LIFE ALTERING.

Thanks!

Courtney

very interesting topic, Cal – and one close to my heart, too (as it seems to relate to many others as well).

one of our strongest skill is being able to justify our own behavior, for good or bad. it would be easy for me to switch what i’m working on (and i often do!) just because i “feel” like i’m going to like the new project more.

it’s very likely that pattern will play out again with another new project, we’ll never achieve depth, and ultimately, may feel unfulfilled with our work.

layered in there may also be self-sabotaging behavior, stemmed by the fear of success (crazy, i know)! it’s important to note if we’re actually getting close to our goals and aren’t looking for ways to keep our status quo well…status.

another point to offer: if we feel complete with a project and are absolutely drawn to something else, then we have every right to pivot and change direction. it’s just a matter of not honoring that “shiny new object” sensation over and over again!

thanks for inspiring a great conversation with many points!

Sometimes we can think a thing to death. Cal’s advice is right on. Undergrad is the time for foundational work. Specialize in grad school, and what’s more, apply to grad school(s) based upon the faculty whose research interests match yours at the time you apply. Your interests often change over time.

P.S. Cal, just found your site today, and woohoo! love it. Read your “…Straight A” book this semester and used many of the strategies in it to help me ace my first full semester of grad school.

People, if you haven’t purchased this, you are missing out on the BEST study skills book out there for college students.

Cal,

I had come across your website a few months ago. I cannot tell you how impressed I am with the information you provide. I find it incredibly practical, inspiring and unbelievably helpful to those that visit your website. From my point of view, as a psychiatrist (for whatever that is worth) you are making a difference. That is an amazingly wonderful thing.

I would like to do a feature on my weekly podcast about the ideas contained within this particular article. I want to do so in a way that respects your authorship of this article and gives you proper credit.

Could you just let me know how I may appropriately use this article in my show? I just want to be respectful and give proper credit to you. Please know, I have recommended your website to my patients and they love it!!

Keep doing what you are doing. You are making a difference!

Peter Zafirides, MD

I find myself mixed on this as well. I understand the need to develop skills first before going into a very specific project, but wouldn’t those skills also be possible to work on while working on the specific project?

I ask this mostly because I’m in a similar position…well, except I’m a high school students who’s taken electronics tech classes and done an internship in electrical engineering. I’m planning on majoring in engineering when I get to college. I’ve also been obsessing over the technology of three-dimensional printing (at my internship I worked on a Makerbot, a DIY 3D printer). I’ve been considering building my own. Would this be “getting too specific” or would it be “doing a project that works on skills”? Where’s the line on that?

Experience counts for depth.

Common deletion happens when we assume its one way as long we havent defined the baseline of what we do.

Enjoyed this.