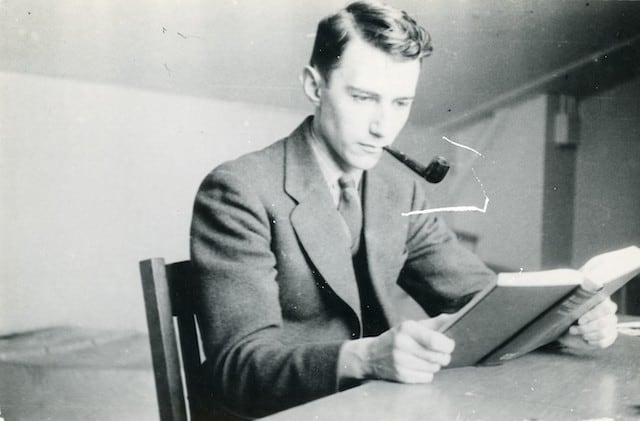

In 1937, at the precocious age of 21, an MIT graduate student named Claude Shannon had one of the most important scientific epiphanies of the century. To explain it requires some brief background.

Before coming to MIT, Shannon earned two bachelors degrees at the University of Michigan: one in mathematics and one in electrical engineering. The former degree exposed him to Boolean Algebra, a somewhat obscure branch of philosophy, developed in the mid-nineteenth century by a self-taught English mathematician named George Boole. This new algebra took propositional logic, a fuzzy-edged field of rhetorical inquiry that dated back to the Stoic logicians of the 3rd century BC, and cast it into clean equations that could be mechanically-optimized using the tools of modern mathematics.

Shannon’s degree in electrical engineering, by contrast, exposed him to the design of electrical circuits — an endeavor that in the 1930s still required a healthy dollop of intuition and art. Given a specification for a circuit, the engineer would tinker until he got something that worked. (Thomas Edison, for example, was particularly gifted at this type of intuitive electrical construction.)

In 1937, in the brain of this 21-year-old, these two ideas came together.