When I was a young graduate student at MIT, I was impressed by Alan Lightman, a one-time physicist, who turned toward essay and novel writing and ended up accepting a humanities professorship and starting the school’s science journalism program.

What initially caught my attention about Lightman was the following line, which to this day remains defiantly perched at the top of his academic homepage:

“I do not use e-mail, but you can reach me at my MIT office: [mailing address]”

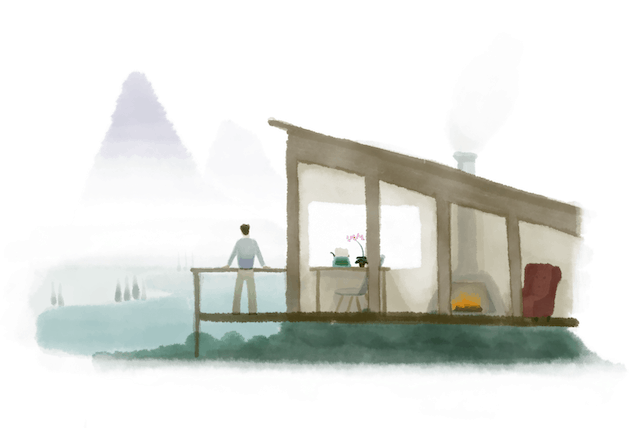

But what really captured my imagination was when I heard about Lightman’s island.

In his late 30’s, at a time when the was looking for a quiet place for him to write and his wife to paint, Lightman stumbled across a 30-acre island in Casco Bay, Maine, shared by six families. There are no bridges or ferries servicing the island; no electricity; no plumbing; no internet or phone. Lightman and his wife spend their summers at this isolated outpost decompressing and creating.

“The world is moving at much too fast a pace: everybody is plugged in 24/7, everything is rush rush rush,” he said in a recent interview. “The island in the summer is a place where we can unplug, slow down, listen to ourselves think.”

I was reminded of Lightman while recently reading about Mary Somerville, the 19th century polymath who was among the first women to be elected to the Royal Astronomical Society. As Somerville recalls in her autobiography, as a child, she would find ways to evade the chores and social activities that defined the lives of women of her social station to instead explore the nearby sea coast:

“When the tide was out I spent hours on the sands…I made collections of shells, such as were cast ashore, some so small that they appeared like white specks in patches of black sand. There was a small pier on the sands for shipping limestone brought from the coal mines inland. I was astonished to see the surface of these blocks of stone covered with beautiful impressions of what seemed to be leaves; how they got there I could not imagine, but I picked up the broken bits, and even large pieces, and brought them to my repository.”

Her collection, begun during those childhood expeditions, is now housed at the college named in her honor at the University of Oxford.

Lightman and Somerville’s lives were defined and elevated by regular exposure to depth: extended periods of undistracted time during which the mind can focus intensely on one thing, or purposefully on nothing at all. In both cases, this depth was hard-won. Lightman’s island was remote and offered primitive living conditions. He had never used a boat before committing to a house that required one to access. Somerville, for her part, had to battle the gender expectations of her era to carve out a deeper life. It never came easy.

But they invested the effort because, as I argue in Deep Work, we can find evidence from psychology, neuroscience, philosophy and theology that all supports the same conclusion: humans thrive on concentration and presence.

Which brings us to the last five months: a period in which such moments of depth were lost to the daily waves of anxiety and uncertainty.

In my previous Focus Week essay, I recommended unplugging to provide your brain some breathing room. Here I’m recommending that you put this breathing room to good use by reintroducing yourself to the pleasures of concentrating without distraction on something difficult but rewarding; to rediscover, in other words, the necessity of depth.

Read more