The Remarkable Life of Erez Lieberman

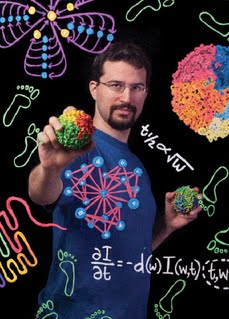

Last week, a reader sent me a profile of the scientist Erez Lieberman. Now I’m obsessed.

Lieberman is a Junior Fellow at Harvard’s elite Society of Fellows and a Visiting Faculty member at Google. He’s a boldly interdisciplinary mathematician who prizes interesting projects above all else. “I’m always on the lookout for new methods that I think will open up whole new domains,” he explained.

Lieberman cracked the 3D structure of human DNA, showing that our genes are packed in an esoteric geometric whimsy known as a fractal globule.

He used graph theory to improve our understanding of evolution.

He sifted through Google’s massive database of scanned books to search for statistical evidence of cultural shifts.

The six papers he lists on his web site were all published in either Science or Nature. Two were cover articles. He’s been featured on the front page of the New York Times, was a Tech Review 35 under 35, and won the $30,000 MIT-Lemelson prize for innovation.

He’s also only two years older than me.

Lieberman represents my dream of an academic career done right. He swings for the fences with wildly interesting projects which earn him recognition, but more importantly also earn him freedom. At this early point in his career, he can work on what he wants and where he wants. He’s constructed a life centered on intellectual novelty, and it’s remarkable.

The reason I’m writing this post, however, is what happened after I first encountered Lieberman’s story.