A Novel Dissertation

I began working on my PhD thesis in the summer of 2008. I defended a year later, in early August, 2009.

There’s nothing unusual about this timing. What was unusual, however, was my approach.

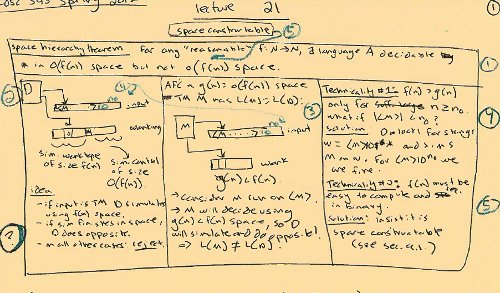

By June 2008, I had a fair-sized collection of peer-reviewed publications. The standard practice in computer science would be for me to take the best of these results, combine them, fill in the missing details, add a thorough introduction, and then call the resulting mathematical chimera my dissertation.

To me, naive as I was, this sounded like a waste of a year. So I decided I would prove all new results.

This strategy worked fine for a while, keeping me engaged and happy, but then, in April, 2009, things took a turn toward the difficult. It was during this month that I accepted a postdoc position that would start in September. This meant that I had to defend my thesis over the summer. Suddenly the allure of tackling all new results began to wane.

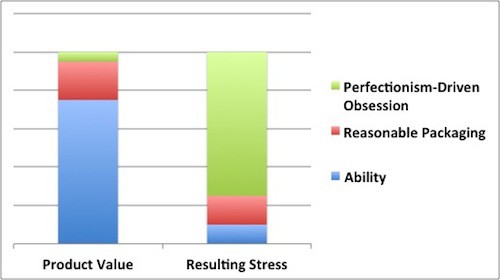

Here’s a scenario that became common:

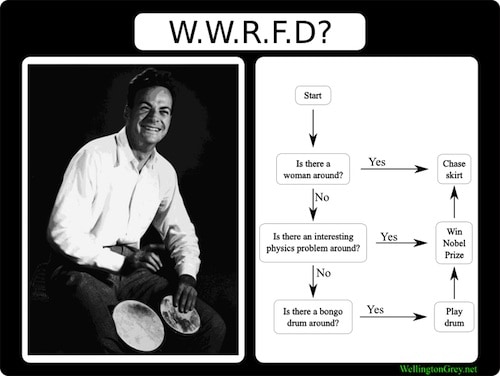

- I would be working during the day on an important proof.

- At some point in the late afternoon I would find a flaw.

- A helpful voice in my head would point out that my whole future depended on finding a fix — without a fix, it argued, the thesis would crumble, I would be kicked out of graduate school and end up homeless, likely dying in a soup kitchen knife fight.

- After heading home, I would continue, obsessively, seeking a fix — ruining any chance at relaxation that night.

After two weeks of this exercise, I decided something needed to change.

It was then that I innovated my shutdown philosophy…