Facebook Arrives

I remember when I first heard about Facebook. I was an undergraduate at Dartmouth College. At the time, the service was being made available on a school-by-school basis, and, one spring day in 2004, it finally arrived at our corner of the Ivy League.

Many of my friends were excited by this event. They were surprised when I didn’t join.

“What problem do I have that this solves?”, I asked.

No one could answer.

They would, instead, talk about new features it made available, like being able to reconnect with people from high school or post photos. But my lack of ability to connect with old classmates or to publicize my social outings were not problems I needed fixed.

“Every product and service ever invented offers new features,” I’d respond, “but what problem do I have that Facebook’s features are solving? Why should this product, of all products, earn my attention?”

Again, no one could answer.

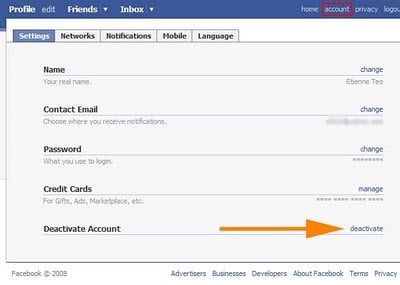

After a while, I stopped asking this question, and just moved on with my life without a presence on Facebook. Ten years later, I still have never had a Facebook account — nor any social media account, for that matter — and have never missed it.

I have close friends. I still have lots of readers and still sell lots of books. And I’ve preserved my ability to focus, allowing me to make a nice a living as a theoretician.