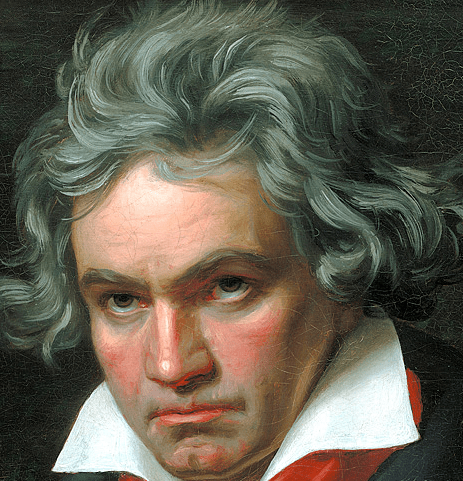

Writing in 1801, at the age of 30, Ludwig van Beethoven complained about his diminishing hearing: “from a distance I do not hear the high notes of the instruments and the singers’ voices.”

As Arthur C. Brooks recounts in a 2019 op-ed, published in the Washington Post, Beethoven “raged” against his decline, insisting on performing, pounding pianos to ruin in a futile attempt to hear his own notes. By the age 45, he was completely deaf. He considered suicide, one friend reported, but was held back only by the force of “moral rectitude.”

It’s here that Beethoven’s story veers toward legend. Cut off from the world of sound around him, working only with musical structures dancing through his imagination, at times holding a pencil in his mouth against his piano’s soundboard to feel the consonance of his chords, Beethoven produced the best music of his career, culminating in his incomparable Ninth Symphony, a composition so daringly new that it reinvented classical musical altogether.