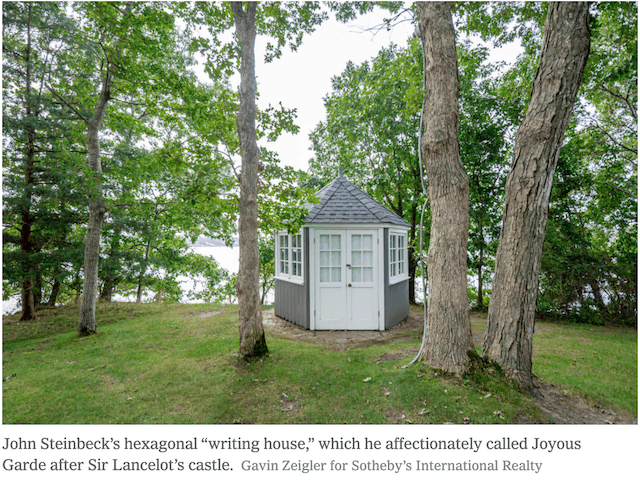

Good news: if you have $17.9 million available, John Steinbeck’s 1.8 acre waterfront retreat is now for sale. It’s tucked onto a grassy peninsula in Upper Sag Harbor Cove, and features a pool, a long pier, and two cozy guest cottages. Arguably most important is the hexagonal, 100-square-foot “writer’s house” overlooking the water.

Encountering this real estate listing sent me down a brief but entertaining Steinbeck-at-Sag-Harbor rabbit hole. He bought the house in 1955, I discovered, 16 years after The Grapes of Wrath. He subsequently split his time between his apartment on the Upper East Side and his Sag Harbor retreat, which he inhabited mainly in the summer, and eventually dubbed “my little fishing place.”

Steinbeck would write in the morning, often in his waterside hexagonal shed, but as revealed in letters, he’d sometimes instead escape out into the harbor in his fishing boat. “I can move out and anchor and have a little table and yellow pad and some pencils,” he wrote a friend. “Nothing else can intervene.”

With his writing done, Steinbeck would then relax:

“Afternoons were spent fishing or hobnobbing at Sal and Joes or Baron’s Cove resort, or with Truman Capote, Kurt Vonnegut, and other writers at The Black Buoy, his beloved standard poodle in tow.”

Another source talked of how he would wander over to the docks in rubber boots to chat up the local fishermen.

Though it’s easy to be distracted by the more gaudy elements of Steinbeck’s summers, like his deep work on an anchored boat, it’s actually these final details — the languid afternoons — that stuck with me. Steinbeck represents the tail end of a period during which many intellectual types embraced a sort of heroic inactivity. They understood overload to be the foe of inspiration, and put their non-professional lives into an uneasy but necessary alliance with productive output.