An Obsessive Digression

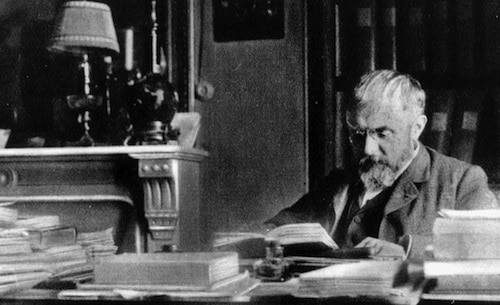

For the past two weeks, I’ve been trying to prove a bothersome theorem. It’s not particularly flashy, but I need it for a paper. More importantly, it felt like it should be easy and I took it personally that it’s not.

Predictably, I began to obsess about this proof — by which I mean I took to returning to the proof again and again during breaks in my working day. It became a staple during my commutes to and from work, and began to hijack blocks of time from my otherwise carefully constructed schedules.

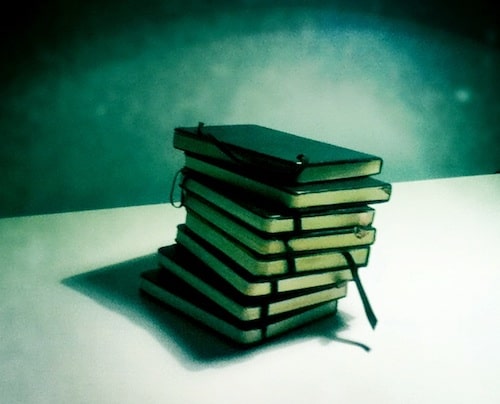

Earlier this week, the weather was nice, so while waiting out the traffic at home in the morning I sat outside in my backyard with my grid notebook (something about grid rule aids mathematical thinking) and, as I had been doing, noodled on the theorem.

Except this time: something shook loose.

I scribbled notes for an hour, drove to campus, and set about trying to formalize my new idea.

It didn’t work.

But now I had the scent. Long story short, six hours later I had a proof that seems to work for a more or less reasonable version of the problem (time will tell).

I started that day with a pretty elaborate time block schedule. It was ignored; as was my e-mail inbox; as were several pretty important administrative obligations. But the important thing is that I think I finally tamed that damnable theorem.