A Tale of Two Productivities

As a graduate student I was known for being organized. I was reminded of this a couple weeks ago when I attended a computer science conference along with many of my old lab mates.

What I also remember is that I always felt indifferent about this reputation. To be organized is a nice thing. But it didn’t take me long at MIT before I realized it’s also unrelated to what matters most: the consistent production of high value results.

We don’t often talk about this division but I think it’s crucial. There’s a lot written about task productivity (the ability to organize and execute non-skilled obligations), but much less written about value productivity (the ability to consistently produce highly-skilled, highly-valued output).

As I’ve settled more into life as a professor, I’ve been increasingly fascinated with value productivity. It’s not that task productivity lacks importance — it has saved me much stress — but I think the value variety is what will rule in an increasingly competitive knowledge economy.

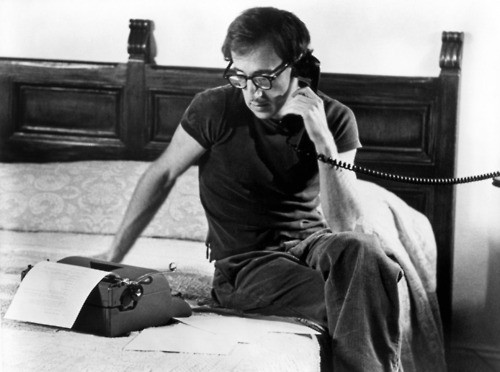

It is with this fascination in mind that I spent some time recently re-watching Robert Weide’s deep diving documentary on the life and habits of Woody Allen. When it comes to value productivity, Allen is an unquestionably good place to start. He’s written and directed 44 movies in 44 years, earning 23 Academy Award nominations along the way.

By watching the documentary with an ear for work habits, I picked up the following three ideas that help explain Allen’s astonishingly high level of value productivity…