Each month I strive to read five books, from a variety of genres and levels of seriousness. By popular request, I’ve listed below the titles I completed in December 2021 (for more detailed thoughts on these books see Episode 163 of my podcast):

In the summer of 2020, I launched the Deep Questions podcast. The premise was simple: I answer your questions about all the different topics we … Read more

Each month I strive to read five books, from a variety of genres and levels of seriousness. By popular request, I’ve listed below the titles I completed in December 2021 (for more detailed thoughts on these books see Episode 163 of my podcast):

A reader named Alexander recently pointed me toward an essay he wrote about his experiment avoiding social media for all of 2021. What caught my attention is the fact that Alexander runs an online business as a freelance copywriter. I frequently hear from people who are exhausted by the frenetic, anxiety-inducing churn of social media, but are concerned that without their participation on these services their professional lives will disintegrate. With this in mind, I thought it might be useful to share some highlights from Alexander’s detailed breakdown about what exactly happened to his livelihood when he stepped away from his social accounts for twelve months.

I’ll start with the punchline: Even though Alexander used to make regular use of LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to promote and grow his business, his year without these services did not bankrupt him. Indeed, as he reports, both his business and his email newsletter subscribers grew by 50% during this period. How did clients find him? Google searches, referrals, and repeat work.

Back in December of 2019, inspired by the recent release of my book, Digital Minimalism, I announced what I called the Analog January Challenge. The … Read more

Last week, for the first time in a long time, I made a substantial change to the configuration of my email inboxes.

This might seem somewhat out of character. As readers of A World Without Email know, I’m largely indifferent about using hacks and technical fixes to improve your email experience. The real problem, I argue in that book, is the implicit decision to coordinate so much of your collaborative efforts with unscheduled back-and-forth messaging. This hyperactive hive mind workflow doesn’t scale: once you have dozens of these conversations unfolding concurrently, you have no choice but to check your inbox constantly, as otherwise you might slow down the ongoing collaboration.

According to this analysis, the solution to email overload is not handling messages more efficiently, but instead preventing them from arriving in your inbox in the first place. You must, in other words, replace the hyperactive hive mind workflow with alternatives that do not generate so much unscheduled communication.

Motivated by these ideas, most of my efforts in recent years to tame my email have focused on implementing better processes — methods for collaboration that don’t just depend on dashing off quick messages. And yet, I still found myself recently needing to make a change to the technical details of my communication setup.

Since last spring, I’ve been pursuing the goal of reading five books a month. To meet this mark, I start with a foundation of daily reading, but then, when I get momentum going on a given book, I schedule extra reading sessions in my time block schedule, allowing me to accelerate toward completion. I also include at least one audio title each month, and try to mix together a diversity of genres to keep things interesting.

Recently, on my podcast, I adopted the habit of of briefly reviewing the books I read each month. I thought it might be fun to replicate these reviews here in written form (an homage, I suppose, to my friend Ryan Holiday’s epic and longstanding Reading List newsletter).

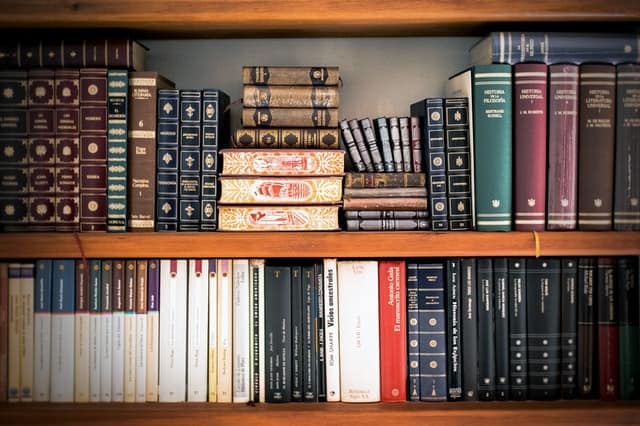

Without additional preamble, here are the five books I completed* in November 2021:

In early 1973, George Lucas was living modestly with his wife, the film editor Marcia Lou Griffin, in a one-bedroom apartment in Mill Valley, a small town in Marin County, just north of San Francisco over the Golden Gate Bridge. Lucas’s situation drastically changed that summer when Universal released his second feature film, American Graffiti.

The movie was a major hit, earning over $60 million in its first year alone, before eventually going on to rake in $250 million in the decades that followed. Given that Graffiti was made on a shoestring budget of only $775,000, it still ranks as one of the most profitable movies of all time. Lucas, of course, enjoyed immense personal benefit from this success. His fledgling production company, LucasFilm, received $4 million from the movie in 1973, an amount worth over $16 million in today’s dollars.

I recently read about this particular beat in Lucas’s long narrative in Chris Taylor’s exhaustively-researched 2014 book, How Star Wars Conquered the Universe. As Taylor details, Lucas resisted the urge to follow the path of his friend Francis Ford Coppola, who had made a fortune the previous year with the runaway success of The Godfather, and then promptly spent the money on a “massive” Pacific Heights mansion and a private jet lease. He and Griffin instead bought a rambling Victorian house on Medway road in the Marin County village of San Anselmo.

What caught my attention most, however, is what Lucas did next.

A few years ago, my family faced a housing dilemma. We lived at the time in our first house, a small cape cod near the top of an elongated cul-de-sac, situated on a bluff above Sligo Creek, a half mile outside downtown Silver Spring. We had two kids who comfortably shared an upstairs bedroom. But then my wife and I decided they needed a new brother, and we soon realized that we might not actually have anywhere to put him.

So we started thinking through options to gain more space. At one point, I landed on what I deemed to be an ingenious plan. We would give up my home office and instead build, in the corner of our small backyard, a custom writing shed. Inspired by the cabin Michael Pollan built in the woods outside his home in Kent, Connecticut, I began to daydream about making that short walk from our back door to a wood-paneled oasis; heated in the winter by a marine pellet stove, and cooled by tilt-open windows in the pleasant DC spring.

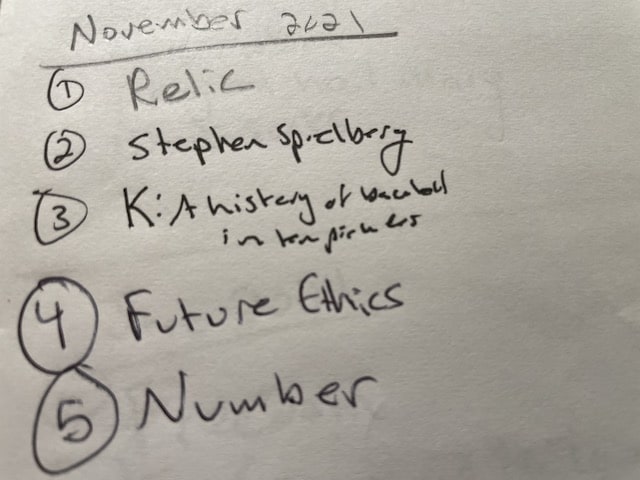

For various reasons, including the potential illegality of cramming an outbuilding of this size into our cramped yard, we ended up instead buying a new house ten minutes down the road. But the daydream of my impractical writing shed lingered.

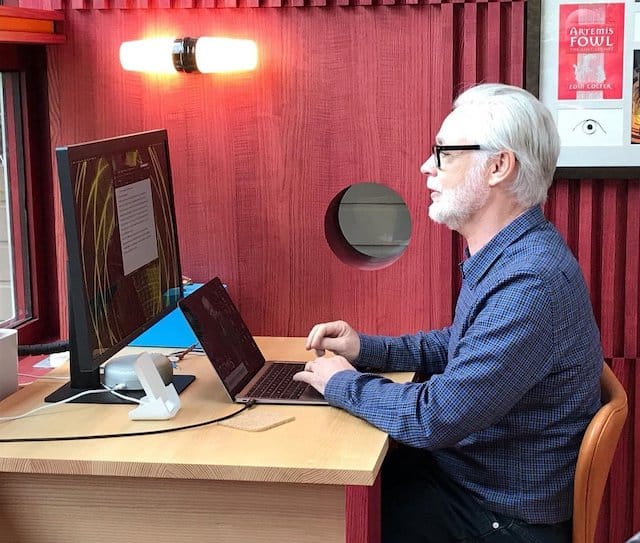

Which is all a long way of establishing the importance of what happened earlier today. I was watching an old episode of a promotional show called Disney Insider with our youngest son (now three), when we were suddenly confronted with a great example of a writer who actually acted on my impulse. The segment in question focused on Eoin Colfer, the Irish author of the massively successful Artemis Fowl book series.