The Decision Problem

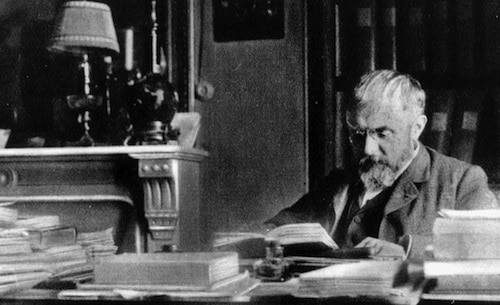

In 1928, the mathematician David Hilbert posed a challenge he called the Entscheidungsproblem (which translates to “decision problem”).

Roughly speaking, the problem asks whether there exists an effective procedure (what we would today call an “algorithm”) that can take as input a set of axioms and a mathematical statement, and then decide whether or not the statement can be proved using those axioms and standard logic rules.

Hilbert thought such a procedure probably existed.

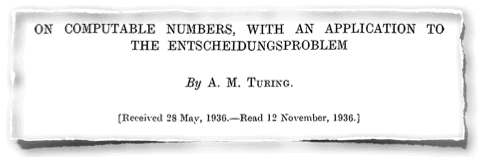

Eight years later, in 1936, a twenty-four year old doctoral student named Alan Turing proved Hilbert wrong with a monumental (and surprisingly readable) paper titled, On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem.

In this paper, Turing proved that there exists problems that cannot be solved systematically (i.e., with an algorithm). He then argued that if you could solve Hilbert’s decision problem, you could use this powerful proof machine to solve one of these unsolvable problems: a contradiction!

Though Turing was working before computers, his framework and results formed the foundation of theoretical computer science (my field), as they can be used to explore what can and cannot be solved by computers.

Over time, theoreticians enumerated many problems that cannot be solved using a fixed series of steps. These came to be known as undecidable problems, while those that can be solved mechanistically were called decidable.

The history of theoretical computer science is interesting in its own right, especially given Hollywood’s recent interest in Turing.

But in this post, I want to argue a less expected connection: Turing’s conception of decidable and undecidable problems turns out to provide a useful metaphor for understanding how to increase your value in the knowledge work economy…

Read more