The Race to Somewhere

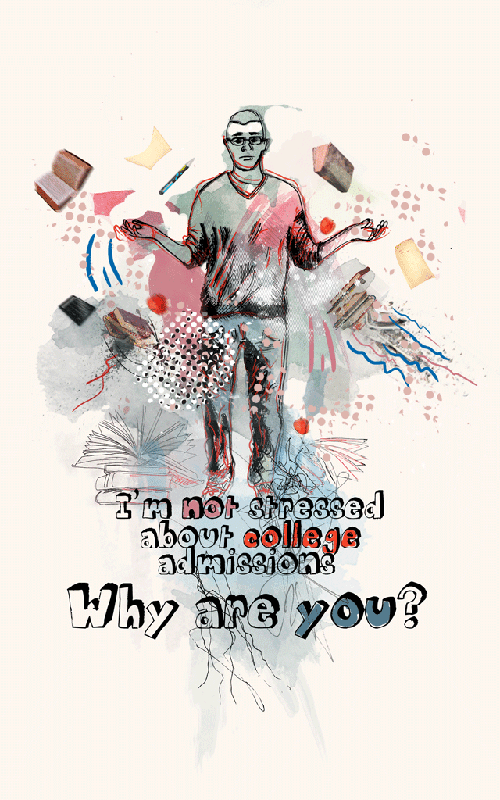

The new documentary Race to Nowhere, following the tradition of movies such as Food Inc. and An Inconvenient Truth, is less about introducing a new idea, and more about providing a clear distillation of ideas already on peoples’ minds. This film, which presents a concerned mother’s investigation of the “high-stakes, high-pressure culture” of the American educational system, provides parents a focus for their otherwise ambiguous unease about rising student stress.

As one mother reacted after a Washington D.C.-area screening: “I think more people need to be willing to take a step back and ask, ‘Why are we doing this?'” She then spread the word about the film to her local PTA.

Like most good issue films, Race to Nowhere separates the problem from the solution. “[The co-directors] admirably convey the complexity of the issue with considerably more compassion than prescription,” complimented The New York Times. But now that this documentary has succeeded, and the issue of student stress is once again a hot topic, commentators such as myself can safely join the “prescription” side of this conversation.

Accordingly, in this essay, I want to present my unconventional view on student stress at the secondary school level: the college admissions process, which is the main driver of student stress, doesn’t have to be a bad thing, and in fact, if approached correctly, can instead become the foundation for a life well-lived.